Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (26 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

Most unusually, the story of the expedition does not take the form of a sequence of static, lifeless and rather dull images; instead the artists have attempted a realism which is rarely found in monumental Egyptian art. The native people, their animals and even their trees are vibrant with life, providing the viewer with a genuine flavour of this strange foreign land and making it difficult to imagine that the artists who carved the fat queen of Punt or her curious home had not actually left

Egypt's boundaries. Unfortunately, the charm and fine workmanship of the individual scenes has attracted the inevitable treasure hunters, and the story is now to a certain extent spoiled by the gaps which mark the position of stolen blocks. The loss of the blocks depicting the remarkable queen of Punt is particularly to be deplored although fortunately one of these blocks, now safely housed in the Cairo Museum, has been replaced in the temple wall by an exact plaster replica.

Throughout the text Hatchepsut maintains the fiction that her envoy, the Chancellor Neshi, has travelled to Punt in order to extract tribute from the natives who admit their allegiance to the distant King Maatkare. In fact the expedition was a simple trading mission to a land which, occupied by a curious mixture of races, seems to have been a well-established trading post. The Puntites traded not only in their own produce of incense, ebony and short-horned cattle, but in goods from other African states including gold, ivory and animal skins. In return for a vast selection of luxury items, Neshi is to offer a rather feeble selection of beads and weapons; as Naville, a man of his time, commented in 1898, he offers the men of Punt ‘… trinkets like those which are used at the present day in trading with the negroes of Central Africa’:

30

The necklaces brought to Punt are in great number; they perhaps had only a slight value; but they pleased the Africans, as they now please the Negros, to whom articles of ornament which are in themselves things of no intrinsic value, or cheap stuffs with showy colours, or cowries are often given in exchange, things valueless in themselves, but much in request amongst these African peoples.

31

Naville forgets to mention that the fact that Neshi was accompanied by at least five shiploads of marines may have encouraged the Puntites to participate in this rather one-sided trade.

Punt had many desirable treasures, but was particularly rich in the precious resins (myrrh,

Commiphora myrrha

, and frankincense,

Boswellia carterii

) which Egypt needed for the manufacture of incense. Incense could be made from either a single aromatic tree gum or a mixture of them; a favourite Egyptian incense known as

kyphi

was said to contain as many as sixteen different ingredients, but the recipe is now unfortunately lost. Incense was burned in great quantities in the daily temple rituals, and employed in the formulation of perfumes, the

fumigation of houses, the mummification of the dead and even in medical prescriptions, where those suffering from sour breath – women in particular – were advised to chew little balls of myrrh to relieve their symptoms. This might explain why the odour of Amen, in the legend of the divine birth of kings, is reported to smell like the odours of Punt. The Punt brands of incense were highly prized, but could not be found in any great quantity within Egypt's borders where trees of any kind were rare. Therefore Neshi was dispatched to obtain not only supplies of the incense itself, but living trees complete with roots which could be re-planted in the gardens of the temple of Amen. The thirty or so trees or parts of tree depicted in the Deir el-Bahri scenes seem to represent either two different species or the same tree at different seasons, as one type is covered in foliage while the other remains bare. The trees have been tentatively identified as representing frankincense and myrrh, although it is unfortunate that different experts cannot agree which type of tree is which.

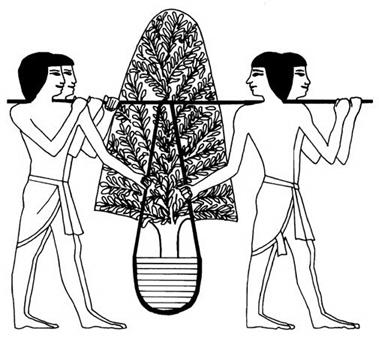

Fig. 5.2 Tree being transported from Punt

Five Egyptian sailing ships equipped with oars are shown arriving at Punt where the sailors disembark into small boats, unload their cargo and make for the shore. Here they find a village set in a forest of ebony, incense and palm trees, its houses curious conical structures resembling large beehives made of plaited palm fronds and set on poles above the ground so that their only means of access is by ladder. The inhabitants of the village are a curiously mixed bunch, some being depicted as black or brown Africans while others are physically very similar to the Egyptian visitors. However, the animals shown are clearly African in origin. There are both long- and short-horned cattle, long-eared domesticated dogs, panthers or leopards, a badly damaged representation of a creature which might possibly be a rhinoceros and tall giraffes, which were considered so extraordinary that they were led to the ships and taken back to Egypt. The tree-tops are full of playful monkeys and there are nesting birds, a clear indication that it is spring.

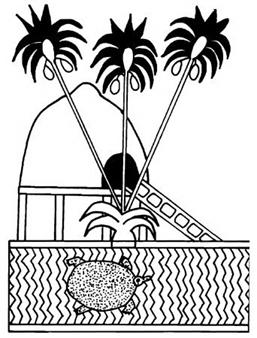

Fig. 5.3 House on stilts, Punt

The Egyptian envoy Neshi, unarmed but carrying a staff of office and escorted by eight armed soldiers and their captain, is greeted in a friendly manner by the chief of Punt who is himself accompanied by his immediate family of one wife, one daughter and two sons. The slender chief is obviously not of Negro extraction; his skin is painted a light shade of red, he has fine Egyptian-style facial features and an aquiline nose. It is his long thin goatee beard, and the series of bracelets adorning his left leg, which mark him out as a foreigner. However his grotesquely fat wife, with her wobbling, blancmange-like folds of flab and enormous thighs emphasized by her see-through costume, presents a marked contrast to the stereotyped image of the upper-class Egyptian woman as a slender and serene beauty. Her appearance must have seemed

extraordinary to the ancient Egyptians and even Naville, normally the most courteous of commentators, found the portrait of the queen and her already plump young daughter highly unnerving:

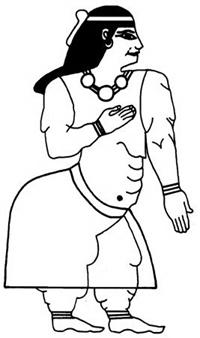

Fig. 5.4 The obese queen of Punt

Their stoutness and deformity might be supposed at first sight to be the result of disease, if we did not know from the narratives of travellers of our own time that this kind of figure is the ideal type of female beauty among the savage tribes of inner Africa. We can thus trace to a very high antiquity this barbarous taste, which was adopted by the Punites [

sic

], although they were probably not native Africans.

32

We can only wonder how the queen of Punt, who is evidently too fat to walk and is therefore carried everywhere by a disproportionately small donkey, ever managed to ascend the ladder which led to her home.

The Egyptians present the natives with a small pile of trivia; amongst the trinkets shown we can distinguish beads, bracelets, an axe and a single dagger in its sheath. The Puntites appear to receive these less than impressive offerings with delight, and cordial relations are so well established that Neshi orders that the appropriate preparations be made to entertain the chief of Punt in his tent:

The preparing of the tent for the royal messenger and his soldiers, in the harbours of frankincense of Punt, on the shore of the sea, in order to receive the chiefs of this land, and to present them with bread, beer, wine, meat, fruits and all the good things of the land of Egypt, as has been ordered by the sovereign [life, strength, health].

33

It is possible that the expedition spent several weeks travelling westwards to the interior of Punt escorted by Puntite guides and collecting

both ebony and incense. It would almost certainly have been necessary for the ships to wait for the reversal of the winds which would carry them back to Egypt. However, when next we see the expedition the ships are being loaded for the return journey. Egyptians and Puntites labour side by side as baskets of myrrh and frankincense, bags of gold and incense, ebony, elephant tusks, panther skins and a troop of over-exuberant monkeys are all taken aboard. Truly, ‘Never were brought such things to any king, since the world was.’

34

The return journey is left to the imagination, presumably because it would not have added to our appreciation of the vast treasure being carried to Egypt. Instead, we skip directly to the unloading of the ships in the presence of Hatchepsut herself. We are told that this momentous event occurred at Thebes although, given that the River Nile was not yet connected to the Red Sea, it seems unlikely that the ships were able to sail directly from Punt to Thebes. There is, however, some evidence to suggest that sea-going ships, originally constructed in the Nile Valley, were dismantled and carried in kit-form overland both to and from the Red Sea port of Quseir. The

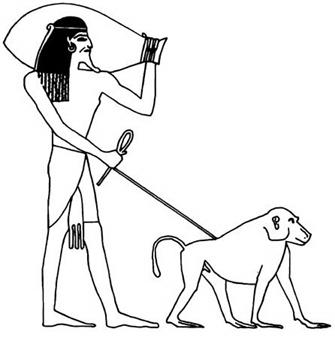

Fig. 5.5 Ape from Punt

final leg of the sea–land–river return journey, the voyage from Coptos to Thebes, could therefore indeed have been by boat. Papyrus Harris I, a contemporary text detailing the reign of the 20th Dynasty King Ramesses III, includes an explicit description of a return from Punt:

They arrived safely at the desert-country of Coptos: they moored in peace, carrying the goods they had brought. They [the goods] were loaded, in travelling overland, upon asses and upon men, being re-loaded into vessels on the river at the harbour of Coptos. They [the goods and the Puntites] were sent forward downstream, arriving in festivity, bringing tribute into the royal presence.

35

The Red Sea coastal area, with its desert conditions, lack of fresh water and great distance from the known security of the Nile Valley, was not considered a suitable place to live, and no fixed ports were maintained along its length. Quseir, the traditional departure point for voyages south, did not in any case have the satisfactory harbour facilities which would warrant the establishment of a permanent port.