Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip (5 page)

Read Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #General, #United States, #Automobile Travel, #Biography & Autobiography, #20th Century, #History

Much was made of the fact that Truman paid for his own car. Exactly how much he paid, however, is unknown. The list price was around four thousand dollars, but Truman probably paid much, much less. “I suspect the agreed price might have been one dollar,” speculated a Chrysler official who was familiar with the transaction. Harry Truman was a man of scruples, to be sure, but some deals were simply too good to pass up.

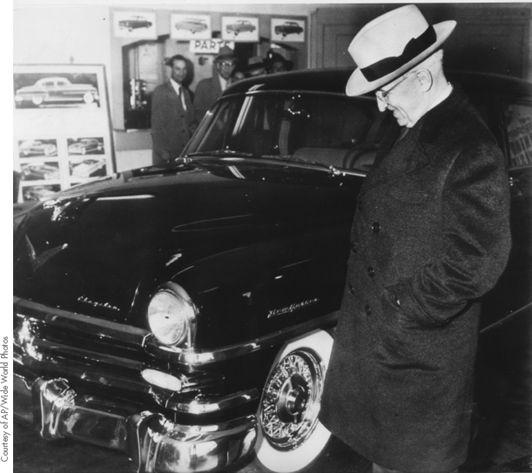

Harry beams as he inspects his new 1953 Chrysler New Yorker at the Haines Motor Company in Independence, February 16, 1953. “It’s got so many gadgets on it I’ll have to go to engineering school to handle it,” he said.

Truman took delivery of the New Yorker at the Haines Motor Company in Independence on February 16, 1953. It was a black, four-door sedan with chrome wire wheels and whitewall tires. The interior was a beautiful tan velour. Powered by a 331-cubic-inch V-8 FirePower engine (later known as a Hemi), it boasted all the latest technological innovations, including a PowerFlite automatic transmission, power steering, and power brakes. “It’s got so many gadgets on it I’ll have to go to engineering school to handle it,” Truman cracked. Chrysler sent a young engineer named Frederick Stewart to Independence to help Harry get acquainted with the vehicle. With Stewart driving, Harry in the passenger seat, and Bess in back, they spent about two hours driving the back roads of Jackson County, with Stewart explaining the car’s many features.

Finally it was Harry’s turn to get behind the wheel. “It was soon apparent that Mr. Truman hadn’t done much driving recently,” Stewart remembered, “so we sort of made this drive a little refresher course on driving the very latest in automobiles.” Eventually Harry got the hang of things, and the three of them headed back into town. Driving past the Jackson County Courthouse, Truman told Stewart how there had been ten thousand dollars left over after the courthouse was built, so Truman arbitrarily decided to have a statue of his hero, Andrew Jackson, erected out front. It was, he told Stewart, the only thing he had ever done in his political career that he could have been put in jail for.

The next day, Truman sent K. T. Keller a thank you note. “That wonderful Chrysler arrived yesterday,” he wrote. “It certainly is a peach of a car and I can’t tell you how very much I appreciate the courtesies which you have extended to me. I’ll think of you whenever I take a ride and that will be rather frequently you can be sure.”

Harry Truman’s 1953 Chrysler New Yorker is still out there somewhere, in a dusty garage or weathered barn. According to Mark Beveridge, the Truman Library’s registrar and unofficial “car guy,” the Chrysler is owned by a collector who “wishes to remain anonymous.” I was eager to see the car, of course, so I asked Beveridge if he would be willing to forward a letter from me to the anonymous collector. “No,” he said apologetically. Beveridge hopes the collector will eventually donate the Chrysler to the museum, and he didn’t want to do anything that might jeopardize that acquisition.

I wasn’t about to give up that easily, so I placed ads in classic car newsletters—nothing. I posted pleas on Internet bulletin boards—still nothing. I even enlisted the help of a private investigator, again to no avail. My quest, however, did turn up another 1953 Chrysler New Yorker, much like Harry Truman’s.

Back in 1971, Alan Hais was twenty-five years old and just starting his first job as an environmental engineer for the District of Columbia. He was looking for a cheap car to get him around town when he spotted an ad in the paper for a 1953 New Yorker. The asking price was three hundred dollars. Hais and a friend drove out to Fredericksburg, Virginia, to check out the then eighteen-year-old car, but when he learned it had ninety-seven thousand miles on it, Hais got cold feet. When he and his friend stopped for burgers on the way home, though, Hais reconsidered. “It was a good solid car,” he remembered. “So I said, well, we might as well go back.” Hais drove the car home, with his friend following just in case.

Since then, Hais has gone on to a long and successful career, mainly working for the Environmental Protection Agency. And the New Yorker has gone from his beater car to his pride and joy. Over the years he has lovingly restored it “piece by piece,” rebuilding the carburetor, replating the chrome, replacing the brakes and exhaust system. He had it repainted its original color: “Hollywood maroon.”

I went to visit Alan on a warm, humid spring day. The skies were cloudy, and when I pulled into the driveway of his home on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, he was already outside waiting for me. He was eager to take the Chrysler out before it rained. He carefully backed the car out of his garage, the door of which was barely wide enough to accommodate it. I hopped in and we went for a drive.

Harry’s New Yorker was a four-door sedan. Alan’s is a two-door convertible, but in most other respects the cars are identical. It is a massive machine, measuring nearly eighteen feet in length and weighing around forty-three hundred pounds. The interior is gorgeous, especially the instrument panel, a half-circle with a speedometer surrounded by four simple gauges for gas, oil pressure, engine temperature, and amplitude. Directly above the ignition is a cigarette lighter.

As we cruised along country roads at forty to fifty miles per hour, Alan explained that 1953 was a transitional year for the automobile industry. Immediately after the war, most cars were just warmed-over versions of prewar models. But by 1953, automakers were beginning to innovate. “They were experimenting with a lot of things,” Alan said. “But they didn’t get them all quite right.” I asked for an example. “Well,” he said, “the power brakes are pretty unreliable.” The laws of physics being immutable, this was not a comforting thought. “By 1955,” Alan continued, “the horsepower race started, and you started to see the first traces of fins, which really went over the top in ‘57 and ‘58.”

After a few minutes Alan turned to me. “Do you wanna drive it?” he asked. I hesitated. Of course I wanted to drive it. But I also didn’t want to wrap his pride and joy with the unreliable brakes around a telephone pole. “Maybe up the driveway,” I said. But Alan, to his credit, was insistent. “Drive it,” he said, bringing the car to a stop in the middle of the road. “There’s very little traffic.”

I climbed behind the giant three-spoke steering wheel and put the car in gear. I don’t know how Harry felt the first time he drove his New Yorker, with a Chrysler engineer sitting next to him in the front seat, but I was a bit self-conscious driving with Alan beside me. Alan, however, seemed to relish the rare opportunity to enjoy his New Yorker from the vantage point of a passenger. “Not many people have driven this car besides me,” he said. “But you’ve got a special case.”

Harry Truman loved cars. Here he is behind the wheel of a 1946 Ford, one of the first models produced after the war ended. In the passenger’s seat is Henry Ford II.

It certainly didn’t handle like the Toyota Corolla I’d rented for the drive out to Alan’s place. The New Yorker had power steering, but when I moved the wheel, it seemed to take the car a moment or two to respond. This, apparently, was another one of the innovations they didn’t get quite right in 1953. It was especially disconcerting when oncoming vehicles approached, but Alan was unfazed. “It’s a little iffy to steer,” he said a bit too nonchalantly. “That’s just one of the things you’ve gotta get used to.”

Alan said he likes to take the car to shows, but admitted that Chrysler collectors can be “oddballs.” “We’re a little more quirky,” he explained. “You go to a show, you can see loads of General Motors cars and loads of Ford cars, but there’s just not nearly as many Chryslers out there, particularly of this era.” Chrysler collectors, he speculated, “go for the underdog.”

I was greatly relieved when I safely pulled the big car into his driveway. Inside his house, Alan showed me an issue of

Consumer Reports

from 1953. Of the New Yorker, the magazine said, “The steering is precise.”

Steering issues notwithstanding, Harry Truman loved his New Yorker. With its wire wheels, whitewall tires, and gleaming chrome trim—not to mention its famous driver—the big black sedan soon became the most recognizable vehicle in Independence, a distinction that made Truman proud. As he tootled around town, running errands with Bess or just taking it out for a spin, passing motorists would honk and wave, bringing that famous toothy smile to the ex-president’s face.

Harry cared for the New Yorker the same way he cared for all his cars: with a meticulousness that bordered on the compulsive. He had the oil changed every thousand miles. He had it washed and vacuumed every few days. He habitually inspected the tires, measuring the tread and air pressure. He religiously recorded every gasoline purchase on a small card he kept inside the glove compartment, so he could calculate fuel mileage.

“He was very particular about his cars,” was how Margaret put it.

In early May, buried in the avalanche of mail that Truman received was a letter that especially caught his attention. It was an invitation from the Reserve Officers Association to address the group’s convention in Philadelphia on June 26. Founded after World War I, the organization not only represented the interests of officers in the military reserves, it also advocated “the development and execution of a military policy for the United States that will provide adequate national security.” Truman, a former reserve officer himself, had helped found the association. Attending the convention would give him a chance to catch up with some old friends. It would also give him a chance to speak his mind.

Since leaving the White House, Truman had remained conspicuously mum when it came to the new administration in Washington. “I’m not going to do or say anything to embarrass the man in the White House,” he told one interviewer. “I know exactly what he’s up against.” Privately, though, he was seething. Before leaving office, Truman had proposed a defense budget of forty-one billion dollars. Eisenhower had proposed slashing that by 12 percent—about five billion dollars. The Republicans believed the reduction was necessary to offset proposed tax cuts. Besides, their thinking went, who needs a big army when you’ve got nuclear weapons? Many Republicans believed atomic bombs alone were enough to deter the Soviets. Eisenhower himself noted that three aircraft with nuclear weapons could “practically duplicate the destructive power of all the 2,700 planes we unleashed in the great breakout from the Normandy beachhead.”

To Truman the cuts were reckless and irresponsible. He believed America needed to project strength with muscular armed forces, not just bombs. Truman was sure the Soviets would regard Eisenhower’s cuts as a sign of weakness and would seek to expand their influence even further. The Republicans, Truman believed, were sacrificing national security—for tax cuts.

Harry Truman was tired of holding his tongue. It was time he spoke his mind. What better place than the Reserve Officers convention? Truman accepted the invitation. It would be his first major speech since leaving the White House.

And he was determined to drive to Philadelphia to deliver it. He’d been wanting to give his new Chrysler “a real tryout” anyway. He would make a vacation out of it. First he and Bess would drive to Washington—just to visit friends, he insisted. Then they would go up to Philadelphia for his speech, then on to New York to visit Margaret and do a little sightseeing. Then they would drive back to Independence, just the two of them, like they used to do back in the old days when he was in the Senate.

Harry was even convinced he and Bess would “enjoy the pleasures of traveling incognito” on the trip, even though theirs were two of the most recognizable faces in the country. To help preserve their anonymity, he would closely guard their schedule and route.

Bess had her doubts. Unlike Harry, she was not under the illusion that they could drive around the country just like any other retired couple. She also knew it would be a physically demanding trip, especially for Harry, who always did all the driving when they traveled in the car together. Yes, back when Harry was in the Senate, they had driven between Independence and Washington all the time. But, as she surely reminded him, that was a long time ago. They hadn’t taken a long car trip together since 1944, when they drove home from the Democratic convention in Chicago—the one at which Harry was nominated for vice president. That was nearly nine years ago.