Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip (18 page)

Read Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #General, #United States, #Automobile Travel, #Biography & Autobiography, #20th Century, #History

Truman then walked over to his old desk in the back row. (At the time it was assigned to Hubert Humphrey, one of the three Democratic senators absent that day.) Truman smiled broadly as the applause continued. When it finally subsided, Nixon invited Truman to say a few words.

“I think I have told you before,” Truman said, “that the happiest ten years of my life were spent on the floor of the Senate. I used to sit in this seat; and I had a seat here for the simple reason that, when the going became too rough, there was always a way to get out.” Truman motioned toward a nearby door. The chamber erupted in laughter.

“This body,” he continued, “of course, has great responsibilities. Its members do not need to be told that by a former senator. But it is up to this body to keep the peace of the world. My ambition has always been to see peace in the world for all nations; and if that happens, it means peace and prosperity for our own nation.

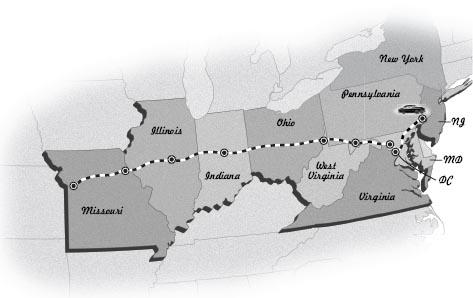

“I have had a most wonderful experience in driving across the country as a chauffeur in an automobile—a privilege which I had not enjoyed for about eight years…. Mrs. Truman watched the speedometer very carefully and we arrived safely.

“I express sincere appreciation for the courtesy which this body has extended to me. I have enjoyed it very much.”

Applause filled the chamber again. Though brief, Truman’s remarks were historic: he was the first ex-president to address the Senate since Andrew Johnson in 1875. (Johnson, the only former president elected to the Senate, served less than five months before dying.)

As he departed the chamber, again escorted by Johnson and Knowland, an impromptu receiving line formed. Truman moved along the gauntlet, shaking hands. All the senators he greeted warmly—save two. William Jenner, an Indiana Republican, and John Marshall Butler, a Maryland Republican, received handshakes that, the

New York Times

noted, were “quick and perfunctory.” Both were allies of Joseph McCarthy.

McCarthy himself was conspicuously—and, some said, prudently—absent.

His private meetings with lawmakers not only gave Harry a chance to catch up on politics. They also gave him a chance to lobby—discreetly, to be sure—for a pension. The issue was not new. After Ulysses S. Grant’s financial problems came to light in 1880, his friends launched a campaign to raise $250,000 in private contributions for a trust fund, the interest from which would be paid to “the surviving ex-President whose Incumbency is most distant in point of time.” Grant, naturally, would be the first recipient. The campaign ended when Grant indicated he would not accept the pension.

After he left the White House, Grover Cleveland was asked if the best way to deal with ex-presidents wasn’t to “take them out to a five-acre lot and shoot them.” “Five acres seems needlessly large,” Cleveland replied, “and, in the second place, an ex-president has already suffered enough.”

In late November 1912, Andrew Carnegie offered to pay future ex-presidents twenty-five thousand dollars a year so they could “spend their latter days free from pecuniary cares in devoting the intimate knowledge they have gained of public affairs to the good of the country.” By limiting the pensions to “future” ex-presidents, Carnegie pointedly snubbed his old trust-busting nemesis Teddy Roosevelt, the only living ex at the time. Roosevelt was too rich to care. “In any event,” he said upon learning of Carnegie’s offer, “[my] interest isn’t in pensions for ex-Presidents, but in pensions for the small man who doesn’t have a chance to save, and who, when he becomes superannuated, faces the direst poverty.” The sole immediate beneficiary of Carnegie’s offer would have been his good friend William Howard Taft, who had recently lost his bid for a second term (largely because Roosevelt had run as a third-party candidate). Taft had hinted at his upcoming need in a speech shortly after the election. “I consider that the President of the United States is well paid,” he said, “… unless it is the policy of Congress to enable him in his four years to save enough money to live in adequate dignity and comfort thereafter….”

Carnegie’s proposal was widely condemned as “undemocratic.” “The idea of ex-Presidents being dependent on private bounty is distasteful to many of Mr. Taft’s associates and friends,” the

New York Times

reported. Taft was forced to disavow the offer, and Carnegie withdrew it. (Taft, as it happened, found a good post-presidential job in 1921, when Warren Harding appointed him chief justice.)

Members of Congress, meanwhile, exhibited an aversion to presidential pensions that bordered on hostility. (They were more generous with presidential widows. At least twelve had been allocated pensions, usually around five thousand dollars a year. They were also more generous with themselves. A congressional pension plan was begun in 1946—too late for Harry, though.)

In 1912, shortly after Carnegie made his pension offer, Albert S. Burleson, a Democratic congressman from Texas, proposed that ex-presidents be made permanent, nonvoting members of the House of Representatives at an annual salary of $17,500. The proposal went nowhere.

In 1948 none other than Senator Robert Taft, son of William, proposed a “substantial” pension—perhaps twenty-five thousand dollars a year—which would allow former presidents “to live in a dignified manner.” He also said exes should be made nonvoting members of the Senate. But, again, Congress did nothing.

In an editorial published shortly before Truman left office, the

New York Times

spoke out in favor of pensions for ex-presidents. “A president nowadays is likely to be a worn-out man when he lays down his office,” the paper wrote. “He shouldn’t have to embark on making a living even in a comfortable and dignified way.”

To Harry Truman, a pension was a matter of principle. Members of Congress got pensions. So did federal judges, and generals and admirals. Yet he got nothing—and he had been commander in chief for nearly eight years! “If you were a rich man before becoming President you went home to your estates,” he wrote in September 1953, “[and] if your means were modest you did the best you could to earn a living…. You were just a private citizen. Ideally, this fits in with our notions of the equality of man. Practically, though, it presents a few problems.”

Even if he didn’t get a pension, Truman argued, the government should at least help him pay his expenses. Truman estimated the cost of maintaining his office in Kansas City at more than thirty-six hundred dollars a month. The government, he believed, should pick up 70 percent of that cost, the remainder being “what I would ordinarily have been out on my own hook if I hadn’t tried to meet the responsibilities of being a former President.”

Still, Congress wouldn’t budge.

In contrast to the bitter denunciations he had sometimes suffered in the editorial pages during his presidency, the newspaper coverage of Truman’s return to Washington was mostly fawning.

A cartoon on the front page of the

Washington Star

depicted Harry as a tourist, a travel guide in his back pocket and camera in hand, standing on the sidewalk, peering at the White House through the iron gate. It greatly amused Truman, who once described the White House as a “prison.” “I’d much rather be on the outside looking in than on the inside looking out,” he joked.

“The friendly quality that was so much a part of the Truman family during their years in Senate life and later in the White House was still with them during their recent visit here,” said an editorial in the

Star

(which had endorsed Dewey in 1948). “It was good to have them back. They looked fine, and it’s nice to know they’re happy and enjoying life. One hopes that they’ll make a habit of dropping into town from time to time. Old friends are always welcome.”

Not everybody was so welcoming. Harry’s old enemies on the right couldn’t abide his carefree return to Washington. “Harry S. can stroll blithely around the nation’s capital, without a care in the world, secretly hugging himself with glee,” wrote the newspaper columnist George Dixon, who noted that Truman had run up a budget deficit of better than six billion dollars in the final year of his administration. “He did the dancing, but Dwight D. has to pay the piper.”

But Harry didn’t give a damn what George Dixon or any of his ilk thought. He had the time of his life on his first trip back to the capital. “As soon as we arrived in Washington,” Harry wrote, “the calendar seemed to have been turned back a year…. It seemed like a dream to relive such an experience. For one solid week, the illusion of those other days in Washington was maintained perfectly. The suite we stayed in at the Mayflower could have been the White House; many of the visitors were the same. Everything seemed just as it used to be—the taxi drivers shouting hello along the line of my morning walks, the dinners at night with the men and women I had worked with for years, the conferences, the tension, the excitement, the feeling of things happening and going to happen—all the same. I was deeply moved by the spontaneous expression of good will shown me.”

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

June 26–27, 1953

O

n the afternoon of Friday, June 26, Harry took the train to Philadelphia. He rode in a private railcar loaned to him by the Pennsylvania Railroad, another “favor” that the former president gladly accepted. Bess and Margaret, meanwhile, drove ahead to New York City in the Chrysler. Harry would meet them there after his speech.

Philadelphia played a pivotal role in Truman’s political career. It was the site of the 1948 Democratic National Convention, where Truman roused languid delegates in a sweltering auditorium with a characteristically pugnacious acceptance speech: “… I will win this election and make these Republicans like it—don’t you forget that!” It was the opening salvo of the whistle-stop campaign.

Five years later, almost to the day, Truman was returning to Philadelphia to deliver the first major speech of his post-presidency.

At 4:12

P.M.

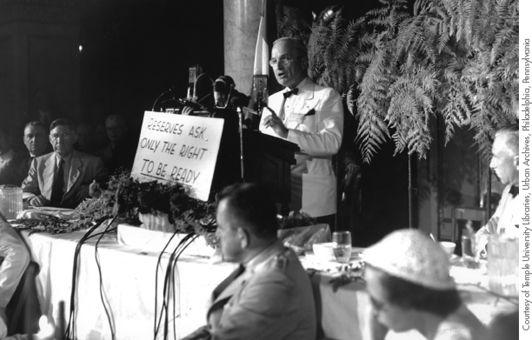

his train pulled into 30th Street Station, where he was greeted by a delegation of city officials as well as a contingent from the Reserve Officers Association. Dressed in a blue summer suit and a Panama hat, the former president looked relaxed and jovial. He was driven to the Warwick Hotel, where he took a nap. Then he was driven several blocks to the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, the site of the Reserve Officers Association’s twenty-seventh annual convention.

Standing in a receiving line before dinner, Truman, now donning a white dinner jacket and black bow tie, greeted another member of the Reserve Officers Association who, like Truman, was a colonel in the army reserves: J. Strom Thurmond, former governor of South Carolina and erstwhile presidential candidate. Back in 1948, Thurmond had bolted the Democratic Party to protest its civil rights platform. “There’s not enough troops in the army to break down segregation and admit the Negro into our homes, our eating places, our swimming pools, and our theaters,” he declared. Thurmond, who had secretly fathered an illegitimate child with his African American maid twenty-three years earlier, ran for president as the candidate of the States’ Rights Democratic Party (aka the Dixiecrats). In his standard stump speech, Thurmond castigated Truman, whom he described as “mad with the lust for power.” What Truman was proposing, he said, was “a program so full of narcotics that the American people are in danger of being lulled to sleep by it. They have named this program ‘civil rights.'”

Thurmond carried four Southern states, capturing thirty-nine electoral votes and ending the Democrats’ stranglehold on the region. Two years later, Thurmond returned to the Democratic Party and ran unsuccessfully for the Senate on a decidedly anti-Truman platform. And just the preceding fall, he’d endorsed Eisenhower, not Stevenson. (Thurmond would get elected to the Senate as a Democratic write-in candidate in 1954. He would hold the seat the rest of his life. In 1964 he switched parties and became a Republican.)

Truman, understandably, didn’t much care for Strom Thurmond, whose disloyalty to the Democratic Party was something that Truman couldn’t stomach. But in the receiving line that night, Harry did the same thing he’d done with Ike on Inauguration Day and Nixon two days earlier. He smiled. He shook Thurmond’s hand. The flashbulbs popped.