Harald (2 page)

She hesitated a moment.

"How far to Valholt?"

"Two hours, easy going. Safe enough; we don't have bandits this side of the mountains. Watch for the oak tree by the turnoff—big branch missing on one side. You'll be there before dark."

"I'd best go then."

"Come visit when the sisters are done talking you dry."

Niall watched her out of sight then turned down the path. As he came into the clearing he saw a black horse cropping the grass in the home field. A child weeding the lower garden saw him, dropped what she was doing, started to yell.

"Niall's home. Niall's home."

He slid off his horse. Someone took the reins from his fingers. He climbed the stairs to the wide porch that ran around the hall. The door opened; Gerda was there, her face calm as always. He caught his mother in his arms. Over her shoulder he saw his father, plainly dressed, rising from the table where the King's messenger sat.

Niall Haraldsson was home.

Haraldholt had been buzzing for days. The King's messenger had brought, along with the royal version of the winter's events, an invitation. His Majesty was holding council in his great castle south of Eston and the presence of the Senior Paramount of the Northvales, his father's ally and general, was greatly desired.

Gerda's first response, once the messenger was out of sight and her youngest son had finished his account of the King's quarrel with the Order, was that her husband should send back a courteous no. The Lady Commander was probably dead. A king mad enough to attack one of his father's allies should not be trusted with the other. It took Harald a day and a half to talk her around; the rest of the household had only guesses as to how.

That settled, there were a thousand things to do—armor to relace, clothes to mend or make, messages to send. Most of them got done. Five days after the King's message arrived, two cats rode east from Haraldholt.

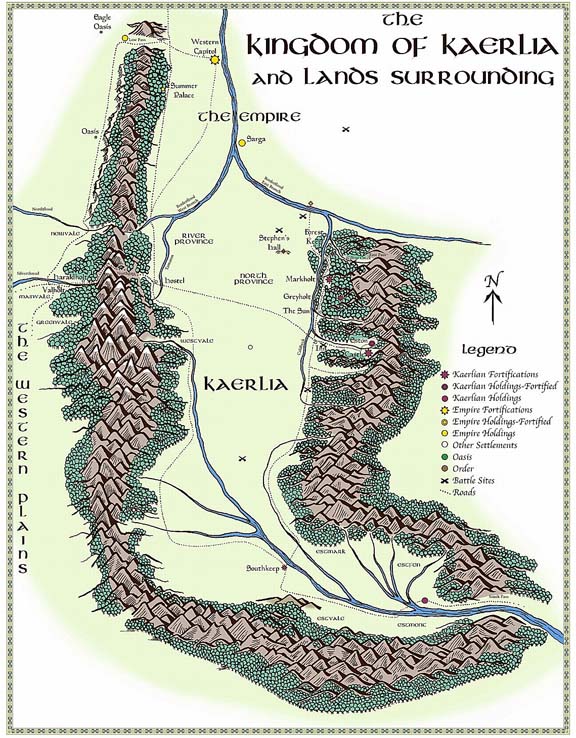

Hrolf and Harald spent the first night in the shelter below the high pass, by good luck empty, the next between Cloud's Eye and the forest. The end of the third put them on the western slope of the foothills. Before dark of the fourth day they had made camp off the trail, a mile above the warden's hostel and the entry posts.

An hour after full dark they broke camp, led the horses down the path and along the forest edge. A mile south of the hostel and its campgrounds they came out of the woods, mounted, rode east. By midnight they reached the west bank of the Tamaron, a sleepy stream swollen with spring melt, forded it. Dawn found them well out in the central plain, hidden in a dip of the land. Most of the day was spent resting, one sleeping while the other stood guard. In late afternoon they mounted again, heading south and east.

For the next three days they rode across the plains. Several times they passed flocks of sheep; the shepherds seemed inclined to keep their distance. Once they passed a burnt out farmstead. Twice too they saw groups of riders. One followed for a while at a trot, but having closed half the distance sheared off.

Harald turned to Hrolf.

"Prudent."

Late in the third day Hrolf stopped his horse, pointed.

"What's that?"

"Village here three years back. Someone put a wall around it."

They rode forward, stopped just outside arrowshot. The high timber wall was pierced by a gate, over the gate a walled walkway. Heads moving on it.

The gate opened. One man came through, on foot, unarmored. Halfway to the two cats he stopped. Harald glanced at Hrolf, slid from his horse. Hrolf leaned down, caught the bridle, held it while Harald walked forward, empty hand raised.

"We come in peace."

"In peace welcome then." Middle-aged, graying hair, wide shoulders—by dress and speech a farmer. Harald hesitated a moment, signed to Hrolf, whistled. The mare trotted over, followed by the packhorse; he led them through the gate. Hrolf rode. Inside the wall the usual scatter of houses and huts, eight or ten new cottages and a surprising number of people. The wall had a walkway along the inside, almost a man's height below the top. A sentry over the gate, another near the middle of each wall. At one side of the gate, next to the stairs leading up, an orderly stack of spears.

"Will you join us for dinner? The boys will take your horses."

Hrolf looked at Harald, Harald nodded. Their host led them into one of the largest of the houses.

"Rest a minute; I'll get you something to drink."

He went through the door at the back; there was a sound of voices. In a few minutes he was back with a clay pitcher of beer.

"You'll be dry from the ride. Dinner soon."

He ate with his guests at the small table—wheat bread, a thick stew of lentils and root vegetables. They shifted to benches by the fire while the rest of the family replaced them at table.

"Long ride?"

Harald nodded.

"Four days over Northgate, three after."

"Welcome to rest here a few days."

"Kind of you. Stay the night, with your leave. On our way in the morning."

"We could use a couple of trained men."

"Done all right for yourselves. Wall looks solid. People hereabouts can use bows. Unless you're expecting a legion at your front door."

"Bandits. Some say they're King's men, some don't. Not much difference that we've seen. Lord's hold is way up in the mountains. We lost a few folk, more cattle, decided to take care of ourselves. We've got spears, bows."

"Good luck to you. Should be home by summer—could pass the word. If two or three of our lads come across, help guard and train, can you feed them through the winter?"

"No problem. A couple of men, with armor, who knew what they were doing would help a lot."

"You could make armor for your men."

"From what?"

"Westkin mostly use hardened leather—not as hard as iron, but light. We use it too, mostly for the horses."

They spent the evening discussing leather hardening and showing their host how to lay out and lace a lamellar coat, the night in their host's bed, at his insistence. After a breakfast of bread and porridge, they fetched the horses. Harald and Hrolf mounted; their host's wife passed up a sack—bread, hard baked to keep, and sausage.

"Food for your ride."

"And many thanks. You or yours have cause to come west, we're the first holding over the pass."

Their host gave him a long look. Harald nodded; they rode out of the village.

Early shall he rise who has designs

On another's land or life

Two more days brought them to where plains turned to forest, running up in hills and valleys into the eastern range. They forded the Caldbeck, turned south on the road that paralleled the forest edge. Before sunset they were rubbing down their horses in the stable of a small inn where the main road met the road running up the valley to Eston and the King's castle. A clatter of hoofs in the courtyard and a loud voice:

"Beer and food. Tell them to take care of the horses. We'll see you inside."

Footsteps went off. Another voice yelled for the stableboy. After a long wait he appeared, was cursed for a lazy fool, started to bring the horses in one by one, muttering under his breath. He saw the two cats, stopped with a start. Harald spoke first.

"Not friendly folk."

The boy looked at them.

"Do you need your horses taken care of too?"

"Grateful for some hay in the manger, grain if you've got it. We can pay. Other than that they should be all right. No hurry."

The boy nodded, led the horse into a stall, went out for another.

Harald reached up to where he had hung his saddle, pulled the saddle mace free, stuck it in his belt, untied the rain cloak, wrapped it about him. His companion spoke in a low voice.

"The horses?"

"Not all night, but they should do for an hour; two safer than one."

Hrolf nodded, armed and cloaked himself and followed Harald into the courtyard.

The inn was a big dining room, kitchen built on at the end, stairs to sleeping rooms above. Most of the party of riders were at the one big table; their leader was arguing with the owner.

"King's men, King's road. You want to be paid for two lousy rooms, send the bill up to the castle."

He turned on his heel, went to join the rest. One of them was yelling for beer. They got it.

The owner saw Hrolf and Harald in the door, motioned them in.

"You see how it is. You're welcome to benches in the hall, but gods know when you'll get to sleep."

"By your leave, we'll eat here, sleep over our horses. Hay's softer than wood."

"Suit yourself—how many horses?"

"Four."

"A silver penny'll feed you and them, buy space for both."

Harald gave him a long look.

"High, but times are hard. I'll throw in breakfast in the morning, bread and sausage to take with you for lunch. Bound up Eston way?"

Harald nodded, paid, found a bench in one corner of the room. After some time the one serving maid got free of the big table long enough to bring mugs of ale, bowls of thick soup, a flat loaf of dark bread. They ate in silence. Aside from the riders, there were only a handful of men and no women.

The big man was talking, his voice only a little slurred.

"I say tomorrow. Bitches aren't expecting us."

"Peaceful, like the lordling said?"

"By the time we're done, peacefullest hold in the damn kingdom. Leave at dawn, lunch in their hall."

He fell silent, glanced around the room. Harald was slumped on the bench, head down on the table, Hrolf draining the last few drops from his mug. Two others were stretched out on benches by the big fireplace, wrapped in cloaks.

Bedded down in the hayloft over the horses, they took quiet counsel.

"Dawn to noon, say a six-hour ride. What holds that close?"

Hrolf thought a moment.

"Big one up the valley?"

"Too close to the castle. If it's still there the King has it—or his cousin's friends in the Order. Besides, I only counted twelve; they wouldn't try that one without more. It'll be some little place, four or six Ladies, a few helpers. No guessing where. Have to follow."

The next morning they heard voices and the noise of horses below, lay still until the stable was empty. Twenty minutes later, packed and saddled, they followed, fresh hoof prints clear on the road south. At the top of the rise they slowed. The road ahead, visible for a mile or more to the next rise, was empty. Harald crossed the flat, took the long downslope at a gallop; Hrolf followed.

Two hours south the road forked—the main south, the tracks east. The eastern road ran up a small valley into the mountains, thinning to little more than a path. Ahead shouts and a heavy thudding noise. Coming over the next low rise in the path they could see the whole tiny battle spread out before them.

To the left of the road the hold, little more than a fortified house. In the stone courtyard a body, mail over the gold-brown robe of the Order. The door shut, three men with a tree trunk trying to open it. Up on the roof two archers shooting down into the courtyard where one attacker lay while another, weapon arm limp at his side, crouched behind his shield. Four more crowded the courtyard, shields up to protect the men with the ram. On the other side of the road two more men, with bows, shooting from behind trees. One of the archers on the roof fell back.

Harald's bow was out, arrow on the string, two more held by the fingers of his bow hand. He nodded right, drew and loosed. The first missed, the second caught the archer high in the back. The man turned, looked uphill with an astonished expression. The third arrow took him in the throat. Harald gave a glance to Hrolf's man, down as well, and rode for the courtyard.

The wounded man at the rear of the attack heard the hooves, turned, died. The ram swung again, the noise echoing through the courtyard; the door split, revealing a slight figure with shield and sword behind it. The ram swung back, fell to the ground; the last of the three carrying it looked with astonishment at the arrow point emerging from his chest, went to his knees, collapsed. There was sudden silence.

The Lady in the doorway stepped forward, shield up. Harald sheathed his bow with his left hand, raised his right palm out and empty, slid down.

"Where are the horses?"

She looked at him, confused.

"They came on horses. Left somewhere, probably with a man to watch them."

"I don't know. Pounding on the door. Mara went. I have to see if she's . . ."

Harald looked up at Hrolf. "The horseholder. Then our horses."

Hrolf rode out of the courtyard; Harald helped the Lady lift the body. The sword the fallen Lady had been holding clattered on the stones. Although he had no doubt, he still felt for a pulse.

"I'm sorry."

"She can't be. So quick. Took the second one's sword arm before he had the shield up. But there were so many. She told me to close the door. I did."