Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (62 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

Once we determine the obvious—but overlooked—role that Congress and popular branches play in shaping our free speech universe, we still have to ask, what should the First Amendment’s guarantee of “freedom of speech” mean? Should it mean that we protect the largest corporations, the largest cable companies, the largest billionaire campaign funders in federal elections? Or does it mean that we adopt a vision that all Americans should have a voice in advocating their viewpoints, in having an ability to persuade other Americans, and being able to associate and organize with others online and in person. Once we have to debate the meaning of freedom of speech not before a judge, but before popular branches of government, then it’s the American people who give meaning to the words of the Constitution through elections, through debates, and through reaching out to elected officials and making their voices heard.

In our democracy, the First Amendment should be read to empower the speech of the little person, the Everyman, not just the billionaire and the cable TV executive. It should not be on the side of the copyright holder, the large media company that claims to have broad “property” rights in storylines, characters, songs, and movies. While they have a claim to their original creations, for limited times under the Constitution, they should not be able assert “property” rights that limit the average American’s ability to speak and communicate with other Americans. But I am just one voice among many. With a First Amendment centered not on judicial opinions but on the very future of the Internet, the public’s voice is what matters most.

The SOPA and PIPA debates were an example of millions of Americans engaging in an important free-speech debate. Lawyers for the copyright industries tried to suggest the debate should turn on technocratic, difficult legal questions reserved for constitutional legal experts who understand the law and 200 years of legal precedents (like me!). But the questions underlying those laws are fit for any citizen. Any American that uses the Internet can have an informed opinion of how the Internet should evolve. SOPA and PIPA were particularly problematic. Those laws would have censored some websites without adequate due process based on the new legal standards of whether they facilitated copyright infringement. The impact of the law would have been to punish companies like Twitter, YouTube, Google, Facebook, Tumblr, WordPress. All these companies enable people to speak and to share. Because people can speak through these sites into the Internet, they can also “facilitate copyright infringement.” Copyright industries wanted all of these companies to be “on the hook” whenever any

of their individual users (up to one billion people) shared copyright-infringing material on those platforms.

It is very expensive and dangerous to be on the hook for the potential infringement of one billion people. It would be dangerous to be a platform for others’ speech. The entire Internet would’ve moved increasingly towards controlled spaces, and spaces for corporate speech. Only someone who could afford a copyright lawyer would be willing to take on the risk of opening up their own platforms for others’ speech. At stake was the “social” Internet.

The American public rebelled at this thought of crippling social platforms. Rather than writing a brief to a court, they made their voices known to the political branches of the U.S. governments, branches that are also bound by the Constitution and bound by the First Amendment. That massive public outcry resulted in pro-free speech outcome—one that benefited the speech of all Americans whose creativity and passions have made the Internet the world’s greatest medium for free and democratic discourse.

CORY DOCTOROW

We are headed inexorably toward a world made of computers and networks—a world strung together by the Internet. And there is no way to communicate on the Internet without making copies. We can’t stop copying on the Internet because the Internet is a copying machine. Literally. With regards to copyright today, copying isn’t a problem. In the twenty-first century, copying is a fact. You can’t and won’t solve copying. If we are going to regulate the Internet and the computer, let us regulate them as the building blocks of the information age, not as glorified cable-TV delivery services.

If anti-circumvention and intermediary liability don’t work in regulating the Internet and computers, what does? Blanket licenses do. Almost all the uses of copyrighted works in the world can be covered by blanket licenses. For example, if you operate a karaoke bar and someone wants to sing Jimmy Buffet’s “Why Don’t We Get Drunk and Screw?” at 3 a.m. (a good time for that number, I’m told), you don’t have to get Buffet out of bed and dicker over whether the royalty for the performance will be $0.10 or $0.25. No, you buy a blanket license that covers all the copyrighted music performed in your premises, from whats played by cover bands to CDs and MP3s servers play on slow afternoons. Blanket licenses are how radio DJs are able to play music. In many countries, blanket licenses are collected to compensate writers for library lending and for the use of their works in university course packs.

Here’s how blanket licenses work: 1) We collectively decide that the “moral right” of creators to decide who uses their work and how is less important than the “economic right” to get paid when your works are used. 2) We find entities that would like to distribute or perform copyrighted works, negotiate a fee structure, and put the resulting money into a “collective licensing society.” 3) We use some combination of statistical sampling methods to compile usage statistics for the pool of copyrighted works; the licensing society divides the money proportionately based on the stats and remits it to rights holders.

This not only is a tried-and-true scheme for paying rights holders for the use of their copyrights but also moves users and intermediaries from the realm of the illegal to the realm of the legal. ISPs around the world are desperate to stave off the legal headaches of policing their users’ music downloading. With blanket licenses, ISPs could advertise that their service comes with “free downloads of all music, ever!” The ISP pays a per-user fee to the collective, and the users and ISP become legit. And just as a radio DJ can legally play music regardless of source, so too could users use any service and any protocol to download any music, knowing that rights holders will get compensated for their activity. “Illicit” download

services could start to focus on delivering excellent user experience, artistdiscovery tools, and bandwidth-friendly network designs that minimize the costs borne by ISPs as a result of user downloading.

The devil, of course, is in the details. How much should each user cost? The sweet spot is the price at which it is cheaper to get legit than it is to skirt the law. How to divide up the money? Collective licensing societies have a poor track record when it comes to fairly distributing the fees they collect. Historically, they have been liable to capture by the major labels, who squeeze out the funds that are rightly owed to smaller competitors and indies. This funny accounting is only compounded when statistical sampling is done using several different methods—surveys, network monitoring, self-reporting—as the way each of these numbers is weighted can substantially alter who gets paid what.

But this is the twenty-first century. If there is one signal characteristic that defines today’s technology world, it is analytics. Every major tech company and ad brokerage is in the business of analyzing hard-to-measure, disparate data sources. A collecting society run with the smarts of Google and the transparency of GNU/Linux has the potential to see to it that the sums collected are fairly dispersed.

This is a complex scheme, it’s true. But it has some great advantages when compared to the current record-industry plan, which is based on attacking fundamental human rights in the hopes of realizing the utterly speculative piracy-free Internet that no one (apart from corporate execs and their friends in government) believes to be remotely possible.

First: It is possible. It’s been done. A lot. It works.

Second: It pays investors. If you’re running a record company, your shareholders want dividends, not pie-in-the-sky talk about the money that will pour in when “the piracy problem is licked.”

Third: It pays artists. This is a policy, created by statute. The statute can be designed to protect creators’ income.

Fourth: It encourages investor competition. A world with four major labels is stupidly anticompetitive. A level playing field, with equal access to distribution for all, makes it easy for new kinds of investment businesses to emerge.

Fifth: It encourages intermediary innovation. Any company that wants to produce a music service today must first negotiate a deal with the big four, a Herculean task that is often more expensive and difficult than building the service itself. Better music service will result in more listeners and more license fees and pay more to more artists and more investors.

Blanket licenses are just one example of how we can craft regulations for the entertainment industry that value creation, investment, and innovation without criminalizing fans or attacking the Internet. The Internet era is not—and should not be—silent on the question: how do we ensure that creators and investors get a chance at money?

That’s all copyright ever really wanted an answer to.

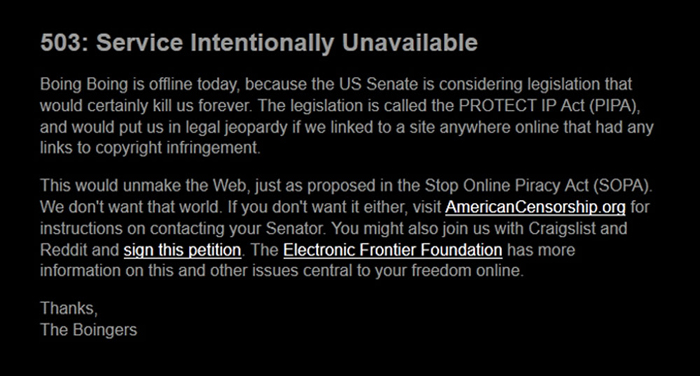

On January 18, 2012 Boing Boing, the website co-edited by Cory Doctorow, blacked out its homepage. Visitors instead saw the message above.

LAWRENCE LESSIG

Lawrence Lessig is the director of the Edmond J. Safra Foundation Center for Ethics at Harvard University, and a professor of law at Harvard Law School. For much of his academic career, Lessig has focused on law and technology, especially as it affects copyright. His current academic work addresses the question of “institutional corruption”—roughly, influences within an economy of influence that weaken the effectiveness of an institution, or weaken public trust

.

No one should doubt the significance of the SOPA/PIPA victory. A decade ago, it would have been literally unimaginable. Ten minutes before it was complete, it was still, to many on Capitol Hill, unimaginable. Yet a netroots movement succeeded in dislodging one of the most effective machines for lobbying on the Hill, through little more than the coordinated activity of millions of souls who depend upon the Net.

Yet however important this victory was, its longterm significance will be lost unless we can learn something here. SOPA and PIPA are just symptoms of a much deeper pathology. And like aspirin with a fever, we delude ourselves if we ignore this underlying disease. The net could play a role in saving this democracy. But not if it rests with stopping stupid copyright legislation.

D.C. is an insiders’ game. Those who work on that inside recognize an incredibly extensive economy of influence that in the end turns upon the ability of lobbyists to deliver results for their clients. Lobbyists can do that because they exploit an obvious dependence: Candidates for Congress need campaign cash. Lobbyists are a reliable channel for that cash—so long, at least, as the clients of these lobbyists get what they want.

Everyone profits when that system works smoothly—except, of course, us. Lobbyists profit, because billings go up. Businesses and other wealthy interests profit, because crony capitalism pays. And Members and their staff profit, because campaigns get funded and Capitol Hill, as Congressman Jim Cooper puts it, remains a “farm league for K. Street.” The business model of government service is temporary governmental service—a temporary stop on the way to a lucrative career as a lobbyist. No one inside wants to threaten this money making machine. Too many just want to get out in time to cash in.

Which leaves it to us, the outsiders, to force a fix for this system. We all must recognize first the particular addiction that Washington has evolved. That addiction is as old as government, though maybe never as profitable. It manifests itself in the drive to bend legislation to profit those who pay to play. It secures itself by making those who ostensibly have the most power—Members of Congress—the most dependent, indeed, fatally dependent upon those (in theory at least) with the least power—the lobbyists.