Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (32 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

The only reason the full Senate did not pass the bill shortly afterwards was because one courageous senator, Ron Wyden of Oregon, stood against the bill from the onset. He understood from the beginning that what was being proposed would fundamentally alter the Internet in a negative way and that it would be unacceptable to the public (once they found out about it, that is). If it was not for his “hold,” then it is likely that PIPA would already be law. Americans owe him, and most importantly his dedicated staff, a lot for their bravery in the face of fierce political pressure.

I will not provide names of any individual staffer I met with, but I want to give folks a peek into how policymakers view these things. Congressional staffers who work for a particular Member of Congress who supported PIPA did not believe there were legitimate concerns about free speech, censorship, cybersecurity, or excessive litigation that we believed the bill would cause. The lobbyists for the bill were very effective at portraying anyone that opposed them as people who did not take piracy seriously and believed that it was fine for artists to have their content stolen. The lobbyists would paint our concerns as just gimmicks to stop the bill, which naturally would make it very hard to be taken seriously if you actually believed that to be true.

Often after raising the fact that the mechanisms in the bill would take down lawful content with unlawful content, the well-trained response would be, “Do you expect us to do nothing to stop piracy?” Sometimes the discussion would degrade into arguments over whether the government should just stand idly by while grandma purchased bad drugs on the Internet and subsequently died—the lead sob story lobbyists used to make the case for passage. In other instances, concerns would be met with the flagrant disbelief that the government could ever harm an innocent in going after criminals (this was before the

Dajaz1.com

story came out). The mental block to taking these issues more seriously revolved around their belief that PIPA was a good bill and the arguments against PIPA were somehow out of touch. After all, if PIPA was really that bad, wouldn’t the public be complaining to Congress about it?

The worst part of these discussions revolved around Domain Name Server (DNS) filtering, which would essentially allow the government to reroute the roads of the Internet (though never actually taking down the infringing content). The bill’s sponsors were dealing with the fundamental nature of the Internet but had no idea what they were doing. It is also ironic that my point that users could just bypass that filter in seconds with a plug-in or a router setting change, was met with skepticism. I commented to a friend of mine that perhaps I need to bring sock puppets to explain the difference between DNS, Domain Names, and Internet Protocol Addresses.

Now I do not fault anyone for lacking the basic understandings or a router or a broadband modem, but I do fault the lobbies in favor of filtering for exploiting it. Having spoken with engineers who work with law enforcement and deal with cybersecurity on a day-to-day basis, it was breathtaking to me to see how

a mixture of technological ignorance and blind faith in the MPAA and RIAA lobby could be so dangerous. Despite countless hours of intense research done by the Center of Democracy and Technology on how DNS filtering would harm our national security and Public Knowledge’s own understanding of the international implications on human rights should the United States adopt filtering as a policy choice, this provision almost made it into law.

This was only possible because the content industry’s lobbyists engaged in a very sophisticated game of misinformation. I summarized in detail the extent of their misinformation campaign on DNS filtering in a blog post. Essentially while I would explain to an office that DNS filtering is used by countries like China and Iran and that, according to the experts, filtering makes the network vulnerable to cybersecurity attacks, the SOPA lobby would tell Congress that DNS filtering happens all the time for child pornography and malware and that experts have shown it is ok. But that’s technically untrue—Comcast, for example, does not filter anything because that would make its network unsecure.

For those keeping count, more than one hundred forty Internet engineers and cybersecurity experts, including the people that built the Internet, told Congress that filtering is dangerous while a grand total of three individuals said it was totally fine. Another argument was that the mere fact that the cable industry endorsed SOPA was proof that DNS filtering was not that big of a deal. I suppose it is just a coincidence that the NBCU (also Comcast) merely happens to be the largest and most powerful member of the National Cable and Telecommunications Association.

Now, all things being equal, my arguments would win and theirs would lose. But keep in mind that the content industry, through their access to campaign cash and dozens of lobbyists, was able to gain direct access to Members of Congress to spin their story, while my capacity to inject the truth was limited to just me and a few other public interest advocates. Simultaneously, in order for our concerns to reach the attention of Members of Congress, the public needed to force them to care.

Only a very small number of people in Congress were actually hardcore supporters of SOPA and PIPA. A substantial majority of staff were skeptical about the effectiveness and the constitutionality of the proposals. The challenge here, though, is that true courage on Capitol Hill is scarce—particularly if the public is silent. This is not the fault of any staffer or legislator, because I think most of us tend to conform to what seems to be inevitable. Rather, a lot of Capitol Hill operates on a “safety in numbers” mentality because it is politically safer to be with a group. That is why it is so rare to see individual senators stand up on any particular issue (with some rare exceptions).

Congressional staffers are also responsible for both informing their boss and protecting their boss on a multitude of issues. In debates where the public is silent, the issues the players in these offices often concern themselves with are determined by the influence lobby and campaign money that is prevalent in the

political system. If they do not have the confidence that the public will have their back in a tough election—especially in the age of Super PACs—because they did the right thing, they will almost always do the wrong thing. During the months of PIPA, I met with countless Congressional staffers who were concerned about the national security implications of DNS filtering and the First Amendment concerns raised by the free speech community. However, given the fact that the politics looked extraordinarily one-sided, many staffers and their bosses fell into one of two spaces: a) If so many other offices cosponsored the bill, then maybe our concerns were unwarranted, and b) why should they stick their neck out against a bill that seemed all but certain to pass?

Some may wish the system worked differently and that Members of Congress, on their own accord, would always do the right thing for the public. But I will tell you that this will never happen in a representative democracy if the public itself does not stay informed and engaged with their government. This is why the only players that want you to believe you do not have the power to make your Congress work for you are the very players in Washington D.C. who rely on your silence. The deaths of SOPA/PIPA are proof.

On October 26, 2011, having captured nearly forty senators into supporting PIPA, the content lobby got greedy and pushed the House Judiciary Committee to create the abomination known as SOPA. Throughout the drafting process of SOPA, the public interest community (regardless of political affiliation) was shut out of the process and only major corporations were consulted with a heavy bias towards the movie and music industry. This process was so closed and lopsided that Republican leaders like Rep. Darrell Issa (CA) and Rep. Jason Chaffetz (UT) came out fiercely in opposition to the bills.

In essence, SOPA changed the debate from the original argument for PIPA (targeting foreign websites) to targeting everything Americans use and cherish today on the Internet. SOPA targeted user generated websites and open platforms in a way that would have destroyed the ecosystem of YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr. When I first saw the bill, I was floored that some in Congress would go so far as to engage in a scorched earth policy to fight piracy (and ultimately do very little to curb it).

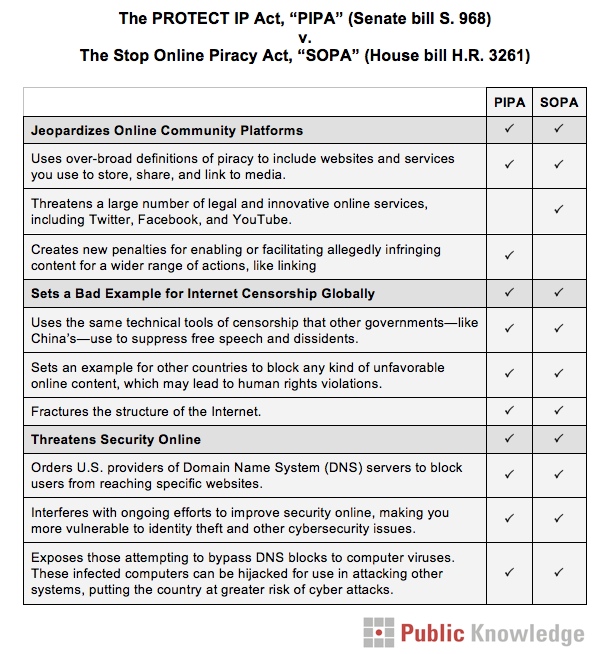

When SOPA was released, Public Knowledge created a quick chart highlighting differences and similarities between it and PIPA.

At the same time, I was hopeful that this overreach would garner the public’s attention because, at this point, we were losing on Capitol Hill. At this point, the powerful coalition of those of us working in Washington, with our fabulous allies working online and in the rest of the country, began to show its influence as they began to show the public what was going on with those bills.

The result was simply amazing. Normally a couple of dozen people watch a Congressional hearing. But here, more than one hundred thousand Americans watched the legislative hearing on SOPA on the Internet and millions of people signed petitions opposing the bill. At that point, I finally began to believe we could realistically water down or outright stop these bills. Once people started

calling Congress, writing letters, and attending town halls to express their displeasure, groups like mine finally had the leverage necessary to start winning.

Now, meetings with offices revolved around the discussion of what needed to come out of the bills in order to address the free speech harms, the cybersecurity issues, and the cost of excessive litigation. I even had one staffer preemptively call me before my meeting to tell me that their boss would oppose the bills and questioned whether we needed to meet at all (but we met anyway so I could explain the specific problems). It was now politically necessary for all of Congress to find out what the Judiciary Committees were pushing, but only because voters back home were both upset and engaged. Once Members of Congress realized it would be wildly popular to be against SOPA and PIPA, they begin instructing their staff to pro-actively contact opponents for more information.

Believe me, when an office receives even one hundred letters on an issue, it garners a lot of attention from the Member of Congress. Having worked on Capitol Hill for more than six years, I can say it is absolute fact that many Members of Congress actually read the emails they receive from their constituents. Some even take the time to make personal calls back if the email or letter is personally impactful. One of the most memorable instances of this during the SOPA debate was when Rep. Steve Cohen (D-TN) spoke about the college student who started their own web business and was afraid that SOPA would bankrupt their dream. Your story and your engagement will always have an impact.

The floodgates were open. Throughout November, as the House Judiciary Committee held its lopsided SOPA hearing (five witnesses for the bill, one against) and the Senate prepared to vote on PIPA, more and more people around the country responded to the information we and our allies were sending out. People around the country also became more aware of the injustice of the legislative process with their own eyes. The House Judiciary Committee started two days of voting on the bill, but due to the heroic efforts Rep. Darrel Issa (D-CA), Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), Jared Polis (D-CO), and Jason Chaffetz (R-UT), opted to wait on finishing work on the bill until after the Christmas break. The Internet Blackout was scheduled for the day the Committee voting would resume, as well as for the planned Senate vote the next week, the week of Jan. 24. I did my part by explaining why the 24th of January was so critical to the entire process and laid it out to the coalition that we either won this fight or lost it on PIPA, not SOPA.

By the time January 18th rolled around, even the most dedicated protectors of the MPAA and RIAA scurried away from SOPA and PIPA. I recall warning one staffer weeks before the blackout that that the MPAA and RIAA had completely lost the public debate and it would be a really bad idea politically to move forward. I gave this warning with confidence because, at this stage, many offices had received on average more than two thousand letters and emails from their voters—a number that had only occurred in response on issues like the Iraq War

or privatizing Social Security. The Internet Blackout made it crystal clear to all in Congress that a vote for one of these bills would be political suicide.

While Public Knowledge and other organizations spent countless hours in strategizing, organizing, distributing information, meeting with Congress, and initializing other components of a national campaign, we were never going to win this fight without your participation. It is only due to your willingness to pick up those phones, tell your friends, write those emails, and visit those town halls that SOPA and PIPA died. I hope that my story will help show you the transformative impact your engagement had on the legislative process because it is possible that the next copyright war will actually not be a war at all but rather a positive agenda for innovation and the Internet. In order for that to be the future, though, you the reader must remain informed, active, and engaged with your government.