Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (12 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

Takedown notices are the measure of first resort for rich and powerful people and companies who are threatened by online disclosures of corruption and misdeeds. Moreover, there are almost never penalties for abusing the takedown process.

In perhaps the ultimate abuse of intermediary liability, Viacom, in a lawsuit against Google, argued that YouTube was complicit in acts of infringement because it allowed its users to mark videos as “private.” Private videos couldn’t be checked by Viacom’s copyright-enforcement bots, and Viacom wanted the privacy flag banned. Under Viacom’s legal theory—supported by all the major studios, broadcasters, publishers, and record labels—online services should not allow users to share files privately, or, at the very least, must allow entertainment corporations access to all private files to make sure they aren’t copyrighted.

This is like requiring everyone to open up their kids’ birthday parties to enforcers from Warner Music to ensure that no royalty-free performances of “Happy Birthday” are taking place. It’s like putting mandatory spy-eye webcams into every big-screen TV to ensure that it’s not being used to run a bootleg cinema. It’s like a law that says that each of the big six publishers should get a key to every office in the land to ensure that no one is photocopying their books on the sly. This is beyond dumb. It’s felony stupidity.

It’s not as though this is the first time we’ve had to rethink what copyright is, what it should do, and whom it should serve. The activities that copyright regulates—copying, transmission, display, performance—are technological activities. So when technology changes, it’s usually the case that copyright also has to change, and it is rarely pretty.

When movies were invented, Thomas Edison, who held key film-related patents, claimed the right to authorize the production of films, tightly controlling

how many movies could be made each year and what subjects these movies could address. The filmmakers of the day hated this, and they flew west to California to escape the long arm of Edison’s legal enforcers in New Jersey. William Fox, Adolphe Zukor, and Carl Laemmle, of Fox Studios, Famous Players, and Universal, respectively, founded the great early studios because they believed that their right to expression trumped Edison’s proprietary rights.

Today’s big five movie studios are rightly proud of their maverick history. But they and the entertainment industry as a whole keep saying that their demands are the existential minimum. “Give us a kill switch for the Internet, the power to monitor and censor, the power to control all your devices, and the right to remake general purpose networks and devices as tools of control and spying, or we will die.”

If we have to choose between that vision of copyright and a world where more people can create and more audiences can be served, where our devices are our honest servants and don’t betray us, and where our networks are not designed for censorship and surveillance, then I choose the latter. I hope you agree.

JOSH LEVY

Free Press advocates for universal and affordable Internet access, diverse media ownership, vibrant public media, and quality journalism. As Internet Campaign Director, Josh Levy leads Free Press’s work to secure an open Internet, strong protections for mobile phone users, public use of the public airwaves, and universal access to high-speed Internet. Before joining Free Press, Josh was the managing editor of

Change.org

, where he supervised the launch of more than a dozen issue-based blogs. Josh holds a B.A. in English and religion from the University of Vermont and an M.F.A. in integrated media arts from Hunter College

.

Before there was SOPA, there was Net Neutrality. Indeed, the fight to keep the Internet open—to stop big companies from becoming the ultimate gatekeepers of what we do, say and share online—has a long history.

Back in 2005, Ed Whitacre, then-CEO of SBC (which soon joined with other Baby Bells to become the reconstituted AT&T) described his company’s vision for the Internet:

There’s going to have to be some mechanism for these people who use these pipes to pay for the portion they’re using. Why should they be allowed to use my pipes? The Internet can’t be free in that sense, because we and the cable companies have made an investment, and for a Google or Yahoo! or Vonage or anybody to expect to use these pipes [for] free is nuts!

1

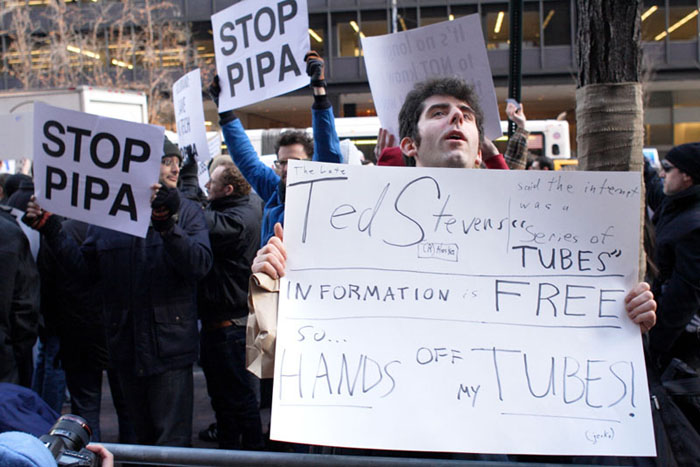

Years after former Senator Ted Stevens (R-AK) called the Internet “a series of tubes,” protestors made sure to express their displeasure at lawmakers’ shallow understanding of how the Internet works. In the photo above, an opponent of SOPA/PIPA tells Congress: “Hands Off My Tubes”

Whitacre’s so-called “shot heard ‘round the Web” jumpstarted the Net Neutrality movement, made up of more than two million activists—including Internet superstars like Tron Guy and Ask a Ninja—and a bipartisan collection of hundreds of organizations united under the

SavetheInternet.com

umbrella.

Net Neutrality’s initial rise as a hot-button issue was notable—suddenly a relatively obscure piece of Internet policy was coming up everywhere from the Daily Show to the messaging for Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign. And it was the first time Internet users realized they were a politically powerful constituency. As for tactics, it was the first time we, in the words of organizers at the time, “used the Internet to save the Internet.”

In fact, from 2006 through 2010, activists, civil society groups, academics, artists, bloggers, and everyday Internet users laid the groundwork for effective networked activism. If it weren’t for these efforts, the anti-SOPA Internet blackout on January 18, 2011 very likely would not have had close to the same reach and impact.

From the time most users started going online in the mid-1990s, they assumed that the Internet was simply “open.” When you clicked a link—and waited for your dial-up modem to transfer data at a glacial speed—there was no reason to think that

MyWebsite.com

wouldn’t load at the same rate as

YourWebsite.com

.

In fact, it’s essentially illegal for phone companies to give preferential treatment to websites or censor the content that flows over these telephone network connections.

That’s because these connections are just that: they’re transmission lines that carry network users’ messages. The phone company that provides the transmission line isn’t allowed to decide what you say or who you can talk to when you use its network.

This de facto “Network Neutrality” forms the basis for the Internet’s historical openness. Sir Tim Berners-Lee could have adopted proprietary technologies to build his vision of a web of interconnected documents. Instead, he opted for openness when inventing the software that became the Web.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, was one of the key Internet figures to speak out against SOPA/PIPA. Twitter is one of the ways he was able to help spread the word about the threat, including by re-tweeting messages from contributors to Hacking Politics.

But then along came cable and DSL. The advent of high-speed broadband connections in the home changed—and is still changing—the ways in which we communicate, learn about our communities, find entertainment, share information, and engage with politics.

This new delivery system also changed—for the worse—the way the Federal Communications Commission regulates Internet access. In 2002, the FCC responded to lobbying from the phone and cable companies and made the terrible decision to reclassify high-speed Internet access as an “information service” and exempt it from most of the Communications Act’s requirements. These rules had kept dial-up service neutral and required phone companies to open up their lines to competing ISPs.

In 2005’s controversial Brand X v. FCC case, the Supreme Court upheld the agency’s decision to deregulate. The FCC’s action and the Supreme Court ruling exempted broadband from some of the longstanding “open access” requirements that apply to other communication services.

2

It was the moment executives at companies like AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, and Time Warner Cable had been waiting for. They had started to both fear and loathe the Internet’s emergent, people-powered culture. Their top-down corporate empires were built not on innovation, free speech, and inclusion, but on controlling markets and squelching new competition.

The phone and cable companies’ aggressive push to control not only the pipes we use to communicate, but the content that flows through those pipes, prompted Internet users to act. It was time to start the movement to Save the Internet.

The

SavetheInternet.com

coalition launched in April 2006. It quickly grew to include more than eight hundred organizations, an unlikely alliance covering the political spectrum and including groups like the Christian Coalition and

MoveOn.org

as well as a host of tech innovators and two million online activists signed a petition supporting Net Neutrality, and thousands of bloggers took up the cause. This show of public support for Net Neutrality derailed a dangerous overhaul of the Federal Communications Act that would have failed to protect Internet openness. This public advocacy morphed into a movement to “Save the Internet” that continues to inspire the larger Internet freedom movement. Sound familiar?

In 2007, Comcast blocked file-sharing protocol BitTorrent for any use at all—even downloading the Bible. This forced the FCC to take action and sanction Comcast, which in turn led to Comcast suing the FCC and claiming the agency lacked the authority to regulate Internet access. Given the FCC’s prior deregulatory decisions upheld in the Brand X case, another federal court ultimately agreed with Comcast.

Then came candidate Obama and his promise that he’d “take a back seat to no one on Net Neutrality.” That stance, and FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski’s early promises, inspired the hope that Net Neutrality would finally be protected once and for all. But the comments from Obama and Genachowski also prompted the phone and cable companies to do what they do best: fight back with lobbyists and lawyers.

These incumbent companies, looking to preserve their old business models in the face of pro-consumer innovations, funneled tens of millions of dollars to nearly five hundred Washington lobbyists. Their mission: drive a wedge into the nonpartisan coalition of Net Neutrality supporters, politicize the issue, further consolidate industry control over Internet access, and kill Net Neutrality before the public got a say. The telecoms invested in fake grassroots operations, corporate-funded “Astroturf” groups that spread misinformation about Net Neutrality to sway policymakers and the media.

SCARE TACTICS: Just as they did during the Net Neutrality battle, incumbent industries rolled out a campaign of scare tactics claiming SOPA/PIPA were needed to stop the loss of American jobs. See these screencaps from a “scary” web video called “Stolen Jobs,” which tries to link file sharing and job losses. Of course, the advertisement was created by a film industry front-group called “Creative America.”

The strategy worked. Thanks to the rise of these industry-funded groups—which helped turn technological neophytes like former Fox News host Glenn Beck into rabid Net Neutrality opponents—Net Neutrality went from being a no-brainer to a supposedly partisan issue that divided left and right, progressive and conservative.