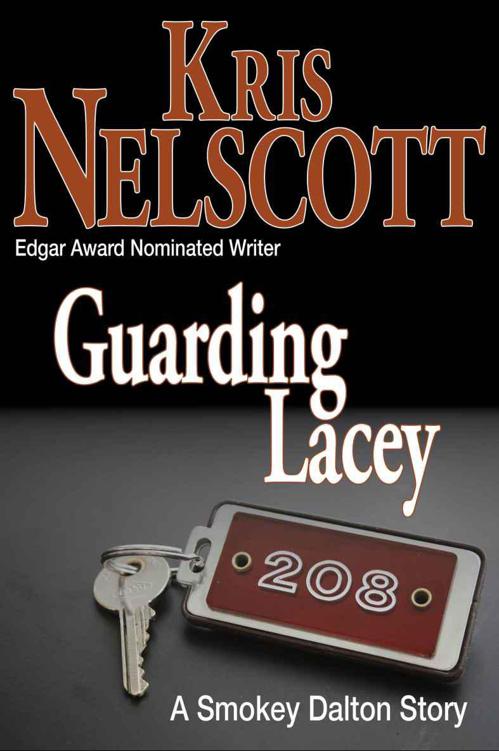

Guarding Lacey: A Smokey Dalton Story

Read Guarding Lacey: A Smokey Dalton Story Online

Authors: Kris Nelscott

Guarding

Lacey

Kris

Nelscott

Guarding

Lacey

Copyright © 2012 by

Kristine Kathryn Rusch

First

published in

Chicago

Blues

,

edited

by

Libby Fischer Hellmann, Bleak House Books,

2007.

Published by WMG Publishing

Cover and Layout copyright

© 2012 by WMG Publishing

Cover art copyright © 2012

by Andy2000soft/Dreamstime

This book is licensed for your personal

enjoyment only. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All characters and

events portrayed in this book are fictional,

and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

This book, or parts thereof, may not be

reproduced in any form without permission.

Table of

Contents

Every other morning, my dad drives me and

my cousins to school, except he’s not really my dad and they’re not really my

cousins. My dad — his name is Smokey — he says we’re family, and I

guess he’s right about that.

He sure guards us like family. When Smoke

drives I known Smoke since I was three; I just can’t get used to calling him

Dad), he lines us up like little ducklings, and makes us walk hand-in-hand into

the school.

The duckling thing is hardest in the

winter. It’s the beginning of 1970 — a decade Smoke says’ll be better

than the last one — and there’s been ice. We lose our balance if even one

person slips (and it’s usually Noreen, who’s six, and never pays attention),

and we just look plain silly.

I’m tired of looking silly, but I know

the dangers if we don’t.

Last year, the Blackstone Rangers tried

to recruit me and my cousin Keith, and Smoke, he beat up a Stone so bad they

ain’t bothered us since. Or not much, anyway. Smoke’s a big guy and now he’s

got a knife scar on his face and he can take on just about anybody. The Stones

look away when they see him. I think he scares them.

They hang in the playground and smoke

cigarettes and they watch us all, especially my cousin Lacey. Smoke says she’s

thirteen going on trouble, and he don’t know the half of it.

Our school is on the South Side, which

the news says gots the worst schools in Chicago. Smoke agrees, but he’s weird

about it; his girlfriend, Laura Hathaway, is rich and white and has what Smoke

calls clout and she says she can get me into one of them private schools and

she’d even pay for it. But Smoke says we gots to do what we can afford and we

don’t take charity from nobody, not even if it’s from someone like Laura.

Besides, he says, we got to do for

everybody, not just make one of us special, so that’s why him and my Uncle

Franklin started the afterschool program for anybody who wants to come and

really learn.

Sometimes I wish Smoke would come inside

our school though instead of staying out front. He thinks we’s safe inside, but

that’s not true. Some of the gang kids still go to classes just to cause

trouble. Last week, Li’l Dan sat in the back of history class and just snicked

his knife open and closed. I almost turned around and took it from him, but

that would get me noticed, and I been noticed enough.

Lacey and Jonathon, they say it’s worse

in the junior high part of the school, which is an attached building at the

other end. They come in with us, go down the hall, and then go through the

double doors which get locked until school’s over since the teachers don’t want

no older kids coming in and “corrupting” us younger ones. But they forget: most

of us gots brothers and sisters who’re older or friends or neighbors and we get

corrupted all the dang time.

I don’t like school much.

Especially this year, and that’s because

of Lace. I’m the only one who sees the problem, and I ain’t sure what to do.

***

Ever since she got into junior high, Lace

has been weird. I mean, she’s always been stuck-up and stuff, and she’s always

worn make-up and clothes that my Uncle Franklin don’t like at all. This year,

Uncle Franklin and Aunt Althea, they make Lacey change dang near every morning

before school, and they’re threatening to ground her.

But it won’t do no good.

Once Smoke or Uncle Franklin drops us

ducklings off at school and we get inside those dented metal doors, Lace heads

to the girls room. If she can’t smuggle her clothes out of the house, she takes

what she’s already wearing and changes it. She rolls up her skirt and tucks the

fabric under the waistband so the skirt is short and double-thick. She ties off

her shirt to show her tummy, and she puts on so much make-up you can’t see her

face at all.

Lately she’s been gluing on them fake

eyelashes and wearing hot pants like Twiggy and big ole clunky high heels. That

kinda stuff is expensive, and I know her family don’t got that kinda money.

The problem is she looks good in it too.

When Lace dresses up, she can pass for eighteen, maybe twenty. Most of her

friends look just dorky in the same clothes, but Lace looks slutty-gorgeous.

She got big tits last year and a waist and a fine ass, so she looks like a

grown-up girl, which is why Uncle Franklin is so worried, I think.

Or maybe he knows what Lace really looks

like.

When she dresses up like that, Lace looks

just like my mom.

***

I ain’t seen my mom in almost exactly two

years. She skipped January 8, 1968. I remember because that’s one week before

my birthday. When I turned ten, my mom was gone and my older brother Joe was

out toking with his buddies. That was Memphis, not Chicago, and Smoke, who was

just this guy down the block who kept an eye on me, bought me lunch and told me

I needed to get to school.

He didn’t know it was my birthday, just

like he didn’t know Mom ain’t paid the rent—again. We got

evicted—or really, I did—and that was the end for Smoke. He’d been

watching over me for a long time, making sure I studied, making sure I ate. But

the eviction, that’s when he took me in.

Mom ain’t got no idea where I am now, not

that it matters. She stayed gone from January to April, and even Smoke, who’s a

private detective, couldn’t find her (not that I think he tried real hard). Mom

ran off with one of her johns again, or maybe she knew the rent was due. She

said she was gonna send money but she never did.

Sometimes I think she’s dead. I seen a

lot of hookers before I moved to Chicago, and they get hurt lots. Knifed or

beat up or worse. Sometimes they get beat so bad they die. That last Christmas,

I was mopping up after Mom all over the apartment, she was bleeding so bad from

her female parts. I ain’t never told Smoke that. He’d give me that shocked look

like he does when I mention my mom, like he can’t believe anybody would ever do

the stuff she did.

But Mom explained it to me and Joe. She

said you have the kinda life she had, you gots to do the best you can. And if

she had it to do over she wouldn’ta chased all them boys when she was twelve

and she wouldn’ta gone with the older guys, and she wouldn’ta never had kids.

Mom, she was only a year older than Lace

when she had my brother Joe. She knew who his dad was, but she never said. Me,

my dad coulda been anyone. Sometimes my mom would take on four or five guys a

night—and that don’t count the quickies in the alley behind our

apartment.

Sometimes her pimp, this guy named Thug,

used to get her to train the new girls. He’d say he could break them in but he

couldn’t teach them the ropes. Mom was in charge of the ropes. She’d talk to

them and by the end, they’d be crying and she’d be yelling at them:

If you’re crying now, you ain’t gonna make

it. You’ll die before the year’s out. You gotta be tough.

Lacey ain’t tough and she ain’t

hooking—at least not yet. But the guys she meets in the schoolyard during

lunch ain’t junior high boys. They ain’t even high school boys. They’s men, and

they’s way too interested.

***

It’s so cold in Mrs. Dylan’s classroom

that I’m wearing my coat, and I’m glad Laura gave me real sturdy boots for

Christmas. Still, the tip of my nose is freezing and I can see my breath.

Mrs. Dylan’s going on about fractions. I

had that a long time ago, so I keep doodling on my notepad while I look out the

window.

Lace is standing underneath an archway.

The graffiti on it is mostly basic crap—Jud loves Susan, stuff like that,

but Lace’s standing under some spray-paint that says

Blackstones Are Stone Cold

. She’s wearing a miniskirt and open toed

high heel shoes and a top tied under her tits. She’s teased her hair into a afro—I

got no idea how she’s gonna get that out before we get to the afterschool

program at the church—and I can see her eye makeup from across the yard.

Her hands are cupped as she leans forward

to light a cigarette. That’s another new habit, and one I’m surprised Uncle

Franklin and Aunt Althea haven’t figured yet. Lace stinks of cigarettes most of

the time.

She’s gotta be cold, but she don’t look

cold. She looks like she’s waiting for someone, just like my Mom used to do,

only there ain’t no road here for them to drive up to, and no way for some guy

just passing by to ask her into his car so she can make a quick twenty.

I can’t tell her none of this. I swore to

Smoke I’d never talk about Memphis ever because I might slip and the secret’d

be out. And the secret’s an important one. I seen something I wasn’t supposed

to and people tried to kill me for it.

Smoke saved me, and then he brought me

here. Thanks to Uncle Franklin, we get to use his last name (and his kids all

think I’m a real cousin) and Smoke got fake i.d.s and stuff. People are

searching for me, but Smoke says we’re safe if we stay quiet.

Still I get nightmares and I know if we

slip we might gotta leave with a moment’s notice. Smoke hates it when I even

think of Memphis because then I can’t sleep and stuff.

But seeing Lacey like that, all tricked

out and me not able to say anything for fear of hurting me and Smoke, scares me

to death.

I talked to Smoke about it last fall,

when things wasn’t quite so bad. We was in the car after dropping off Lacey. He’d

seen her tricked out—well, wiping the crap off her face anyway—and

he tried to tell her what happens to girls who look like that from our part of

town, but Lace didn’t listen, not really.

After everybody got out of the car except

me and Smoke, I asked him, “You don’t think Lace’ll end up like my mom, do

you?”

He looked at me. He’s got this measuring

thing, where he can see all the way inside you, and he was doing that to me

then. He could tell I was worried.

He said, “She won’t end up like your mom.

Lacey has too many friends and family for that. But she could get hurt.”

I remembered how Mom laid in bed for days

sometimes with ice pressed on her face so the bruises would go away, or that

last Christmas, cleaning up the blood she left all over the apartment because

she couldn’t afford no doctor. I didn’t want none of that to happen to Lace.

“Some trick’ll hurt her?” I asked.

“Some

boy

’ll

hurt her. He’ll think she wants to do what your mom used to do. Lacey won’t

understand and—”

“He’ll just do her. I know,” I said real

quick because I didn’t want to think about Lace like that.

That’s when Smoke gave me that shocked

look, like he can’t believe half the stuff I know. Then he blinked, and the

look went away.