Grunts (22 page)

COPYRIGHT © 2010 RICK BRITTON

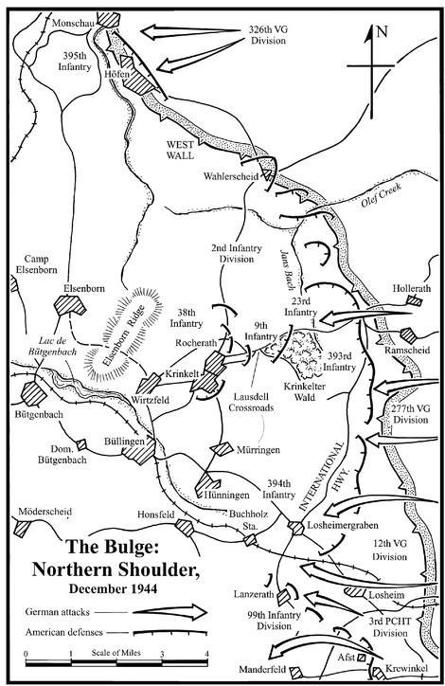

By the middle of December 1944, though, they had seen no extensive action. They had patrolled, stood guard near their frontline holes, huts, or dugouts, and generally learned as much as they could about the ruthless world of frontline combat. Their vast sector consisted of “rocky gorges, small streams, abrupt hills and an extremely limited road net,” according to a divisional report. Much of the area was blanketed with fir and pine forests that were now thick with snow and, on balmier days, mud. At this time of the year, there was only about seven hours of daylight in the Ardennes. Even at the height of the day, though, the trees made it almost seem like night. “Visibility was limited to 100-150 yards at a maximum,” one soldier later wrote. “Fields of fire were equally limited and poor. Fire lanes for automatic weapons would not be cleared for any great distance without cutting down trees and thereby disclosing the position.” It was a confining, almost claustrophobic environment. Throughout December, they could hear the Germans, several hundred yards to the east, moving large numbers of vehicles and soldiers. Patrols confirmed that the Germans were moving these men and this matériel into position, for what purpose no one really knew. The Battle Babies sensed that the Germans were up to something, but they had no idea they were right in Dietrich’s path.

1

Battle Babies Part I: The 394th Infantry at Losheimergraben

Precisely at the stroke of 0530 on Saturday, December 16, the Germans unleashed a monumental artillery barrage on the 99th Division lines. Unlike Guam, Peleliu, and Aachen, this time the Americans were on the receiving end of massive firepower. The shells poured in with “unprecedented ferocity,” in the recollection of one soldier in the 394th Infantry. “Guns and mortars of all calibers, supplemented by multiple-barreled rocket projectors plastered . . . the area.” So unaccustomed were the Battle Babies to large concentrations of German artillery that some of them initially thought the barrage was coming from American rounds falling short. Gradually, though, they realized that the shells were German, particularly when they recognized the familiar, and dreaded, crack of the enemy’s 88-millimeter artillery pieces and the terrifying roar of Nebelwerfer rocket launchers. “It sounded like wolves howling,” Private Lloyd Long, a BAR man in A Company, said. “[We] could hear incoming whistle and whoosh depending upon how close. Direct hits on the huge trees blew their tops off but also splattered shrapnel around.” Huddling in a deep hole, Long heard pieces of shrapnel flying around outside. “It came down like deadly rain for what seemed like hours,” Sergeant Milton Kitchens, a machine gunner in H Company, wrote. “My bunker sustained a direct hit, logs, timber and muddy snow flew everywhere.” Blood was pouring from his mouth and his coat was shredded, but he was otherwise okay. His heavy, water-cooled machine gun was undamaged. Two men on his crew were wounded. Another was on the verge of a mental breakdown. “[He] was bawling like a baby and he looked finished but I kicked his ass up and ordered him to man that machine gun, which he did admirably.”

At the crossroads, two gun crewmen from an antitank unit ran from their gun. They had failed to dig a proper hole for themselves and were frantically looking for cover. In the chaos of the moment, they ran into a line of foxholes manned by a platoon from K Company. The riflemen of this platoon did not know the crewmen. In the recollection of one witness, the crewmen were “oblivious to the several calls to halt, and tore off the cover of one of the foxholes. They were, of course, the instant target of the foxhole occupants.” One of them was killed immediately, the other badly wounded.

2

The pounding lasted for about ninety minutes, and inflicted surprisingly light casualties on the Battle Babies, mainly because most of the men enjoyed the shelter of deep, log-reinforced dugouts or holes. Some had even built sturdy log cabins for themselves. The enemy shells tore up communication wire and shredded many of the cabins, but they did little damage to the soldiers themselves.

The morning was dark and misty. Several inches of snow blanketed the ground. When the shelling ceased, an eerie, wintry silence descended. At 0800, just before sunrise, German infantry soldiers began moving toward the American lines. The darkness provided ideal concealment for them but, for obvious reasons, it also hindered their movement. The German high command arranged for legions of spotlights to bounce their beams off the clouds, thus providing the assault troops with artificial moonlight, which they used to infiltrate in and around the American lines. But the light also made them visible targets for the Americans, who now saw their adversaries emerging, like gruesome phantoms, from the predawn shroud.

At Buckholz, where the 3rd Battalion was in position astride both sides of a north-south railroad line at the extreme right of the 99th Division’s entire front, soldiers from L Company were queued up in a chow line near the railroad station, waiting for breakfast. The company first sergeant, Elmer Klug, was inside the station, standing next to First Lieutenant Neil Brown, his company commander. At nearly the same moment, they saw several dozen men approaching, in march formation, on either side of the tracks. At first glance, they thought these figures in the darkness were men from the 1st Platoon, showing up for breakfast. Lieutenant Brown knew that it was not this platoon’s turn to eat, though. He turned to his NCO and asked: “Klug, First Platoon is coming in for breakfast. What the hell is going on?” The first sergeant looked at them for a moment and exclaimed: “First Platoon my ass! Those are Germans.”

Klug grabbed his M1 carbine, raced outside, ran toward them, and called for them to halt. In response, they stopped, as if shocked. One of them gave a command in German and they began to disperse on either side of the tracks. First Sergeant Klug shot the one who gave the command, and he dropped dead right on the spot. The others dispersed into the darkness. Klug ran back inside. By now Lieutenant Brown was on the phone to battalion, reporting the presence of the Germans. He did not know it, but these were the lead troops of a two-company attack on Buckholz. Within a few minutes, the American chow line quickly dissolved as men ran every which way, finding cover, shooting, trying to figure out what was going on. “Part of the Germans took cover in a railroad car about three hundred yards south of the station,” one soldier recalled. “Others began to run towards this car and towards the woods to the south.” Actually they took cover in at least one car. The cars, and many of the German soldiers, were actually to the north of—or behind—the L Company men.

Small-arms fire crackled as soldiers from both sides looked for targets and opened fire. A BAR man sighted in on one running figure, fired, and dropped him at a range of one hundred yards. The Americans fired several bazooka rounds at the trains but missed. Staff Sergeant Savino Travalini and two other soldiers unlimbered an antitank gun and shot at the boxcars, scoring several hits. The Germans, in or out of the boxcars, were in a difficult spot, exposed to American small-arms and mortar fire. Many of the enemy soldiers got hit and played dead in the snow. “I had a good position in the loft of . . . a barn,” Private John Thornburg, a rifleman, wrote. “I was able to see the smashing of the railway car by the artillery [

sic

] piece. I could also see small figures, discernable as our riflemen, crawling in the snow and firing occasionally.” An American M10 Wolverine tank destroyer rumbled up and fired several three-inch shells into the boxcars. A small group of enemy soldiers emerged from the trains and surrendered.

Soon German mortar and artillery fire screamed in. One shell scored a direct hit on the railroad station. A fragment from the shell glanced off T/5 George Bodnar and ripped into the head of Private Joe Ryan, killing him at once. The shelling continued unabated, prompting all of the men inside the station building, including Lieutenant Brown, to take shelter in a concrete bunker next to the station.

The Germans placed a machine gun atop a nearby water tower, as well as another one four hundred yards south of the station. The guns bracketed much of the open ground around Buckholz Station and the tracks with bullets. In the memory of one officer, they “beat the hell out of us.” This was the officer’s way of saying that some of those bullets struck men, usually with the now familiar sound of a baseball bat hitting a watermelon, spraying blood and tissue as they hit. The plaintive cries of the wounded rose above even the din of the shooting. “When you hear the painful cry of a wounded soldier,” Private John Kuhn, a runner in K Company, wrote, “and you see his life’s blood oozing out in the waist deep snow turning it to crimson red, whether he is friend or foe, it is not a thrilling experience or one soon forgotten.” Captain Charles Roland, the battalion operations officer (S3), watched in horror as “a young lieutenant danced rubber legged until he twisted slowly and revealed a blue bullet hole in the middle of his forehead.” Roland and Kuhn both saw the decapitated bodies—heads sheared off by shrapnel—of the regimental chaplain and his assistant, lying beside their jeep.

Once again, Sergeant Travalini was a difference maker. Somehow, he crawled to within striking distance of the machine gun south of the station and killed the crew with a grenade. In addition, he went back to the antitank gun and fired at least one round into the water tower. As if that were not enough, he took action when he found out that German soldiers had moved into a roundhouse only a few hundred yards from the station. In the recollection of several soldiers in a post-combat interview, Travalini “fired [a] bazooka several times into the roundhouse. This . . . flushed some of the enemy and as they came into view Travalini picked up his M1 and fired into them.” For his exploits, he earned a battlefield commission. The fighting raged around Buckholz much of the day. The Germans were unable to dislodge the 3rd Battalion, so instead they found gaps in the thin American line and, dodging U.S. mortar and artillery fire, swung around to the battalion flanks, trying to cut the Americans off.

3

A mile and a half to the east, much of the 12th Volksgrenadier Division was launching, in broad daylight now, another such relentless push for the Losheimergraben crossroads. This objective was important for the Germans. Taking it would give them a good avenue of advance north, toward the important towns of Murringen, Krinkelt-Rocherath, and the Meuse. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Douglas, commander of the 1st Battalion, had placed all of his companies in and around the crossroads. Company A was on the battalion’s right, between Buckholz and Losheimergraben (which was little more than a cluster of farmhouses and barns on either side of the road). Company B was in the middle, astride the road. Company C held the east, or left, flank. Mortarmen and machine gunners from D Company were sprinkled around in support of the three rifle companies (lettered A, B, and C). The brunt of the attack hit the junction between B and C Companies. “ ‘B’ Company was overrun, with ‘Jerries’ all over the position using some of the foxholes which were in the area,” Douglas later said. “There were more foxholes than there were American infantry to fill them.”

The chaos and confusion were almost indescribable. Private First Class Carl Combs, a rifleman in B Company, was in a well-camouflaged, log-reinforced dugout about fifty yards east of the road, covering a 57-millimeter antitank gun. In the hazy daylight, enemy soldiers brazenly approached, in distressingly large groups. “German infantry showed up to our front and we opened fire, getting quite a few. After three or four such incidents, a tank moved up the road and at close range the 57 knocked it out. It was quite a sight with its ammo exploding.” While the Germans were destroying some of the American dugouts, they had trouble locating Combs and his partner, Fred Robertson. Combs and Robertson kept shooting at large numbers of Germans who were crossing the road east to west, killing more than a few. “It was sort of like a shooting gallery.”

Most of the defenders had a limited field of vision, obscured by the winter haze, the pervasive trees, and the myopic perspective inherent in any well-dug, fortified position. This created a sense of isolation, one so common to infantrymen in combat, who often see only a few yards to their left or right. At the crossroads (and, in fact, at many other spots along the northern shoulder of the Bulge), it was as if each group was fighting its own private war. The actions of NCOs were crucial. They were the ones who set the example, and they often did the fighting and dying. In one spot near the road, a squad leader saw his entire squad wiped out by a group of Germans. In a rage, he grabbed a BAR from one of his dying men and charged at the Germans, all the while firing the weapon on full automatic. The BAR’s

dat dat dum

cadence petered out as the clip emptied. A German soldier killed him from a distance of no more than ten feet. Elsewhere, Technical Sergeant Eddie Dolenc set up a machine gun in a shell hole and zeroed in on an attacking enemy platoon. In just a few minutes, bodies, clad in Wehrmacht field gray overcoats, were literally piled up in front of the shell hole. The German tide swept past the hole. No one ever saw Dolenc again. In another spot, a BAR man climbed atop a log cabin and kept up a relentless fire on any Germans who tried to move within his field of fire. Several other men scurried back and forth, resupplying him with ammunition.