Grunts (13 page)

By the early morning hours of September 17, the fighting petered out. The Japanese attack was a deadly failure. In a day and a half of fighting, some four hundred Imperial soldiers had been killed. Their torn, rotting corpses were draped all over the Point. They lay in mute testimony to the waste, vulgarity, and valor inherent in war. “They sprawled in ghastly attitudes with their faces frozen and their lips curled into apish grins,” Hunt recalled. “Their eyes were slimy with the green film of death. Many of them were huddled with their arms around each other as though they had futilely protected themselves from our fire. They were horribly mutilated; riddled by bullets and torn by shrapnel until their entrails popped out; legs and arms and torsos littered the rocks and in some places were lodged grotesquely in the treetops. Their yellow skin was beginning to turn brown, and their fly-ridden corpses still free of maggots were already cracked and bloated like rotten melons.” Such were the troubling realities of life and death at the Point. In securing it, the Americans had secured their beachhead on Peleliu.

Years later, Russell Honsowetz, a battalion commander in another 1st Marine Regiment unit that did not fight at the Point, smugly claimed that many Marines and historians “made a lot of ballyhoo” about K Company’s desperate battle at the Point. Yet the company, he claimed, “was never in danger.” This would have been news to the men who fought so desperately, and bled and struggled, and watched their buddies die in that awful place. Of the 235 members of the company who went into the Point, only 78 came out unscathed (at least in the physical sense). Hunt lost 32 men killed and another 125 wounded. “Imagine if an officer less brave than George Hunt had the job of securing the Point,” Major Nikolai Stevenson, the 3rd Battalion executive officer, once said in tribute to the captain and his Marines. Knowing that K Company was fought out, Colonel Puller immediately placed the unit in regimental reserve. He knew full well that Captain Hunt’s men had performed brilliantly. He and most other Marines rightly thought of the Point battle as one of the great small-unit infantry accomplishments in World War II.

16

Sheer Misery

In the meantime, Peleliu was turning into a bloody slugging match of pure attrition, exactly the sort of battle the Japanese wanted to fight. The Americans were paying dearly for every substantial gain they made. On D-day alone, the 1st Marine Division suffered nearly thirteen hundred casualties. Late in the day, the Japanese launched a tank-infantry counterattack designed to push the Americans back from a shaky perimeter they had carved out at the airfield. This was a carefully planned albeit ill-advised assault, not a banzai attack. The Americans slaughtered their enemies in droves. “Here they come,” Marines yelled to one another, even as they opened up with every weapon at their disposal. A combination of fire from Sherman tanks, antitank guns, bazookas, machine guns, and rifle grenades destroyed the enemy soldiers, and at least thirteen of their tanks, at close range.

The Japanese attack failed for two reasons. First, their tanks were small, thinly armored, and lightly gunned. They were no match for American antitank guns, especially the bigger Shermans. “Bazookas helped stop the assault, but it was the General Shermans that did the major portion of the damage,” a Marine combat correspondent wrote. Second, the Japanese attacked over the relatively flat terrain of the airfield into a well-prepared defensive position, making perfect targets of themselves. When the fighting petered out, the shattered hulks of enemy tanks burned in random patterns all around the airfield. Treads and turrets were blown off. Side armor was peppered with holes. Flames consumed metal and flesh alike. Dead, half-burned enemy soldiers—some without legs, arms, or heads—were sprawled around the scorched vehicles, sometimes even wedged underneath their grimy treads. The following day the 5th Marines weathered heavy mortar fire to secure the airfield, the campaign’s major objective. But this hardly seemed to matter. From the coral ridges beyond the airfield, the Japanese poured thick gobs of mortar, artillery, and machine-gun fire onto the vulnerable Americans. The American advance was slow in the face of such ferocious opposition.

17

Moreover, the elements were emerging as a real problem. The heat was absolutely brutal. Temperatures reached 105 degrees in the shade, and there was precious little of that to be found anywhere on the beachhead. In the open, the temperatures were at least 115 degrees. It was, in the recollection of one Marine machine gunner, like a “steam room. The sweat slid into one’s mouth to aggravate thirst.” The surviving records most commonly describe the heat as “enervating,” a word that means, according to

Webster’s

dictionary, “to deprive of vitality.” That certainly held true for many of the Marines. Robert “Pepper” Martin of

Time

had covered Guam. At Peleliu, he was one of the few civilian correspondents to see the battle firsthand. “Peleliu is a horrible place,” he wrote. “The heat is stifling and rain falls intermittently—the muggy rain that brings no relief, only greater misery. The coral rocks soak up heat during the day and it is only slightly cooler at night. Marines are in the finest possible physical condition, but they wilted on Peleliu. By the fourth day, there were as many casualties from heat prostration as from wounds. Peleliu is incomparably worse than Guam in its bloodiness, terror, climate and the incomprehensible tenacity of the Japs. For sheer brutality and fatigue, I think it surpasses anything yet seen in the Pacific.”

The stress of combat, combined with the unrelenting heat, made for a miserable combination. There was no way to escape the heat. The sun beat down relentlessly, turning the island “into a scorching furnace,” according to one unit after action report. Everyone was sunburned. Jagged coral rocks poked painfully into tender, sun-baked skin. Men sweated profusely. Their fatigues were salt-stained, dripping wet from their smelly perspiration. Salt tablets helped a little bit, but supplies were low. Some Marines collapsed from heat exhaustion. One officer in the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, saw many such men in his outfit “unable to fight, unable to continue. Some were carried out with dry heaves. Others had tongues so swollen as to make it impossible for them to talk or to swallow. Others were unable to close eyelids over their dried, swollen eyeballs. We lost their much needed strength in a critical phase of the operation.”

Dehydrated, frightened, and exhausted, a few broke mentally under the strain of the heat. Private Russell Davis saw a big redheaded Marine, with dried lips and cherry red sunburned skin, completely lose his composure. “I can’t go the heat! I can take the war but not the heat!” he screamed. Davis watched as “he shook his fist up at the blazing sun. Two of his mates pounced on him and rode him down to the earth, but he was big and strong and he thrashed away from them.” Davis never knew the broken man’s ultimate fate.

18

To make matters infinitely worse, water was scarce. Each Marine came ashore with two canteens of water, a woefully inadequate ration for Peleliu’s killer heat. Most of the men drank their canteens dry within the first few hours of the invasion. “We had practiced water discipline at great length . . . but the body demands water,” Private Richard Johnston, a machine gunner in the 5th Marines, explained. “No matter how strong your will or how controlled your mind, you either drink what water you have or die in not too long a time.” Medical corpsmen were covered with the blood of wounded men, but now had no water to wash that blood off their hands. With no other choice, they treated their patients with filthy, bloodstained hands. After the chaos of the beach assault abated, and the battle settled into a steady push inland to gain ground, shore parties hauled water ashore, mostly in fifty-five-gallon drums and five-gallon cans. By the second or third day, this water reached the frontline fighters. When a five-gallon can reached Private Sledge’s K Company, 5th Marines, he anxiously held out his canteen cup for a drink. “Our hands shook, we were so eager to quench our thirst. The water looked brown in my aluminum canteen cup. No matter, I took a big gulp—and almost spit it out despite my terrible thirst. It was awful. Full of rust and oil, it stunk. A blue film of oil floated lazily on the surface of the smelly brown liquid. Cramps gripped the pit of my stomach.”

The drums and cans had originally been used to carry fuel. Before the invasion, work parties had not properly cleaned the containers. Thus, when they were filled with warm water, the fuel residue mixed with the water, and the metal of the containers, producing a noxious, unhealthy, rusted, repulsive brown liquid. “Smelling and tasting of gasoline, it was undrinkable,” Robert Leckie, a machine gunner in the 1st Marines, wrote. Nonetheless, many Marines, like Sledge, were so desperately thirsty that they drank the tainted water. Some vomited. Others were incapacitated with sharp cramps and had to be evacuated.

Word of the tainted water spread quickly. Soon the Marines began looking for other ways to slake their acute thirst. Private First Class George Parker’s unit found two Japanese bathtubs filled with used bathwater. “It tasted a little soapy but we drank it. We had no choice.” Private First Class John Huber, a runner in Sledge’s company, was with a group of men who found a shell crater full of water and trash. “We filled our canteens and put in halzone [

sic

] tablets to purify it.” Sweaty and thirsty, they chugged down the supposedly purified water. Then someone moved a metal sheet from the crater, revealing a dead Japanese soldier floating facedown in the water. A wave of nausea immediately swept over Huber and the others. “We soon started losing the water . . . and everything else we ate during the day.” One of the men in Private Johnston’s company took a canteen off a dead enemy soldier. Another Marine offered the man two hundred dollars for the canteen. Johnston was struck by how starkly different values in combat were in contrast to life back home. Fresh water was “something that in everyday life most people take for granted.” On Peleliu, it was like gold. The man did not sell the water to his buddy. Instead he gave him a drink for free.

Engineers originally believed that Peleliu offered no sources of fresh water. Within a few days, though, they discovered Japanese freshwater wells. They appropriated those and dug several more of their own. By September 19, the wells were yielding about fifty thousand gallons of water per day, enough to sustain each man with a few gallons each day. In addition, the engineers brought desalination equipment ashore. “All we had to do was run this hose into the ocean,” Private First Class Charlie Burchett, an engineer, recalled. “That thing would pump the water through this unit and it comes out nice, cool, just perfect drinking water.” Within a few days, the water crisis passed. Infantrymen were not exactly awash in water, but they had enough to stave off extreme thirst and dehydration. The heat did not abate, though. Neither did Japanese opposition.

19

The Destruction of the 1st Marines

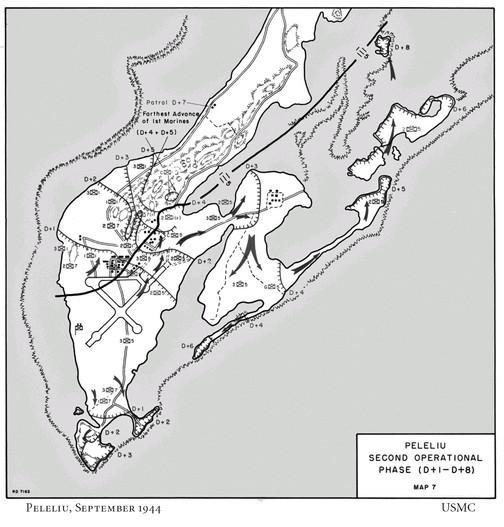

Within three days of the invasion, the 1st Marine Division had already suffered over fourteen hundred casualties, in spite of the fact that the division had not even encountered the most difficult Japanese defenses. In the south, the 7th Marines were clearing out the swampy lowlands of the island. In the center, the 5th Marines were pushing from the airfield across the midsection of the island, fighting their way through plateaus, jungles, and swamps. In the north, the 1st Marines, having overcome the stoutest enemy beach defenses (including the Point), began attacking the daunting ridges of the Umurbrogol. This was the heart of Colonel Nakagawa’s formidable inland defense.

Because of the limits of preinvasion photographic intelligence and inadequate maps, the Marines had little sense of just how daunting the Umurbrogol was until they were enmeshed in it. Already they were referring to this high ground as Bloody Nose Ridge, but it was more than just one ridge. “Along its center, the rocky spine was heaved up in a contorted mass of decayed coral, strewn with rubble, crags, ridges and gulches . . . thrown together in a confusing maze,” the regimental history explained. “There were no roads, scarcely any trails. The pockmarked surface offered no secure footing even in the few level places. It was impossible to dig in: the best the men could do was pile a little coral or wood debris around their positions. The jagged rock slashed their shoes and clothes, and tore their bodies every time they hit the deck for safety.” Even under ideal circumstances, in peacetime, the ground would have been quite difficult to traverse. “There was crevasses you could fall down through,” Sergeant George Peto recalled. “It was a horrible place. If the devil would have built it, that’s about what he’d have done.”

What’s more, it was very difficult to find cover, and the nature of the ground multiplied the fragmentation effect of mortar and artillery shells. “Into all this the enemy dug and tunneled like moles; and there they stayed to fight to the death,” an officer in the 1st Marines wrote. To the Americans, the Japanese cave defenses were unbelievably elaborate. According to one Marine report, they were “blasted into the almost perpendicular coral ridges. The caves varied from simple holes large enough to accommodate two men to large tunnels with passageways on either side which were large enough to contain artillery or 150mm mortars and ammunition.” Some of the caves even had steel doors. All of them were well camouflaged, with nearly perfect fields of fire. Naval gunfire, air strikes, and even artillery only had so much effect against these formidable hideouts. Only infantry and tanks could hope to destroy them, and this had to be done at close range, under extremely dangerous circumstances.

20