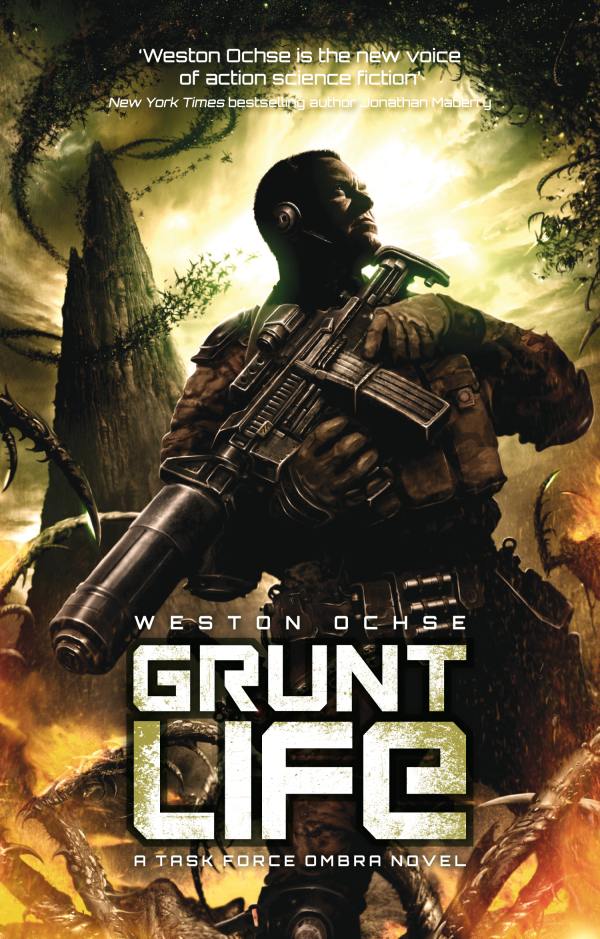

Grunt Life

First published 2014 by Solaris

an imprint of Rebellion Publishing Ltd,

Riverside House, Osney Mead,

Oxford, OX2 0ES, UK

ISBN (epub): 978-1-84997-670-1

ISBN (mobi): 978-1-84997-671-8

Copyright © 2014 Weston Ochse

Cover art by Clint Langley

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners.

“This isn’t a war,” said the artilleryman. “It never was a war, any more than there’s war between man and ants.”

H.G. Wells,

The War of the Worlds

People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.

George Orwell

CHAPTER ONE

I

T WAS MY

love of movies that made me choose the Vincent Thomas Bridge to kill myself. The bridge had gained a certain notoriety over the years. That it had been a shooting location for the films

Gone in Sixty Seconds, Lethal Weapon 2, To Live and Die in LA, Heat

and

The Island

was a bonus. But the chief reason I’d chosen to jump from it was because of my adoration of film director Tony Scott, and the fact that he’d jumped from this very same bridge back in 2012. The director of

Top Gun

,

The Last Boy Scout

,

True Romance

and the incomparable

Man on Fire

had parked his car beside where I now stood, climbed over the rail, and leaped. Some people said that Tony hadn’t meant to kill himself, that a bad combination of drugs had affected his thinking, but I knew better. The truth was that sometimes life was just shit and there was nothing else to be done about it.

I fought against the fear of dying and concentrated on the lights of the harbor. A cruise ship was pulling in. Beyond it, giant cranes glowed with warning lights. To my right, the San Pedro hill was dotted with a thousand lights, each one a home, someone watching television, eating dinner, fucking, or simply staring off into space. To my left was the great plain of Long Beach, where another million souls did the same, unaware that a man who’d been awarded two silver and three bronze stars was about to take a swan dive, just to be rid of all the irrevocable memories of what he’d done, what he’d seen, and what he hadn’t done as a soldier in far-flung countries.

Life was so far behind me, I don’t know when I’d lost it. My current mission was death, and I’d come prepared. I wore black fatigues, boots and gloves. A black skull cap covered my head and I’d painted my face with black camouflage. I wasn’t there to draw attention. I wasn’t there to make a statement. I was there for one final selfish moment, to do something for myself, if only I had the courage of Tony Scott.

I remember laughing at the idea of suicide back before my life happened. I remember talking to my soldiers and scolding them, even ridiculing them, to dissuade them from committing such a final act. I knew it was the wrong thing to do. I knew a person should never give up. I absolutely understood that by killing myself I was dishonoring all of those who had laid their own lives on the line to preserve mine. I’d counseled these very same things on numerous occasions.

So then why couldn’t I follow my own counsel?

I’d stepped over the rail and had backed into the shadow of a beam ten minutes ago. Cars sped past behind me, windows open to catch the sea air, leaving me with a random montage of music by which to die. Grasping the beam, I leaned forward and stared down at the stygian black water. I let my mind wander back to Iraq, to Afghanistan, to Mali, to Kosovo—a badly edited film filled with variations on deathly themes. The deaths of children lying like discarded dolls in the middle of an Iraqi street; at the bottom of a Serbian burial pit; atop a mountain near Tora Bora. The deaths of women, raped and left in a position so much like prayer. The deaths of men, body parts raining like confetti at an end of the world party. Death. Death. More fucking death.

Somewhere along the line I’d ceased to be a hero and had become a death merchant. The very term

hero

had become a laughable idea. “

Who do you think you are, a hero

?” my platoon sergeant had once asked. I’d wanted to respond that I did, that I was, but I knew that he’d already turned that corner where he no longer cared about the mission, but just wanted to survive. Heroism was so far beyond him he might as well have been back on his couch, getting fat and watching other people play sports. It was then that I’d realized that there would come a time when I’d be just like him. If I ever got to the point where I didn’t know the difference between a hero or a zero and lost my grip on what’s right and wrong, I promised myself that I’d end it.

So here I was.

Opened in 1963, the Vincent Thomas Bridge had a clearance of one hundred eighty-five feet, which was like jumping from an eighteen story building. It used to be lit by only a few random bulbs, but in 2005 that had been changed to a hundred and sixty solar powered LED lights. It looked like I was about to leap from the side of an alien spacecraft.

If only.

I tensed my body and prepared myself. I’d decided not to swan dive. That worked in the movies, but it was the sort of stupid gesture that would make me tumble and flail in my final moments. The last thing I wanted at the end was to be out of control. My design was to jump straight out and allow gravity to bring me to grace.

“This could be a beginning instead of an end, you know?”

The voice startled me so much that I almost slipped and fell right then. I saw a figure climbing over the rail. Dressed in a black suit with a white shirt and a black tie, he had a drawn, pallid complexion. Like that actor from

Reservoir Dogs

; what was his name?

“Get out of here,” I snarled.

“It’s a free country,” he said.

Was he being serious? “What the fuck are you doing here?”

“Trying to see if we can convince you to stick around for a while.” The man seemed at ease and spoke with the authority of an officer. Closer now, I saw the pockmarks on his thin face. That was it: I was thinking of Steve Buscemi.

“Do I know you?” I asked.

“No, but we know you. Benjamin Carter Mason, assigned to 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team in Logar Province, Eastern Afghanistan and on leave in Los Angeles, until your untimely death in a house fire.”

Wait a minute. Was I already dead? Was this the synaptic backwards flip of a brain that had already become lifeless?

“I assure you that you’re not crazy.” Mr. Pink grinned and held up a finger. “At least not to the degree to which you think.”

“I didn’t die in a fire,” I said with as much authority I could muster under the circumstances.

“

Au contraire

,” Mr. Pink said, pointing towards San Pedro. A point of light expanded, becoming a raging orange blob. “Seems there was a gas leak. They’ll find a body inside matching your general height and weight. During the autopsy when they check your DNA and fingerprints, they’ll find that they match the deceased. They were lucky the fire didn’t spread to the rest of the apartment complex. Your next door neighbor, Ms. O’Brien, is passed out in her chair, sleeping through a rerun of

Survivor

.”

After a few moments of staring at the fire, I managed to stammer, “Why are you doing this?”

“It seemed to us you were determined to end your life. We hastened to help so that you can start a new one.”

“Who are you?”

“No one you’ve ever heard of.”

I couldn’t help but laugh. I’d seen some version of this in several bad made-for-cable movies. Then again, I’d also seen movies about how insane people believe in conspiracy theories or that everyone is out to get them. A line of dialogue from a Woody Allen film came to mind. ‘

There’s a word for someone who believes that everyone is conspiring against them—perceptive.

’ I also remembered my favorite radio talk show host, The Night Stalker. ‘

Conspiracies are what smart people call the truth, and what stupid people call too complicated to be real.

’

Conspiracy or no conspiracy, whether they substituted my body or not, whether they wanted me to work for them or not, didn’t change the fact that there were people, places and events I could never remove from my mind... things I’d done and hadn’t done, which could only be obliterated by an eternity of nothing.

“You shouldn’t have gone to all the trouble,” I finally said.

Then I jumped.

I was in free fall for three glorious seconds before I hit the net. I bounced once, twice, three times, then got my legs entangled. By the time they lowered me to the ship below, I was calling their mothers things that would shock even a jail house whore.