Grifter's Game (19 page)

Authors: Lawrence Block

The habit doesn’t bite. Mona is not one of the junkies I see from time to time in the café, hollow-eyed and shivering, haggling with the big man. For a drug addict, Mona is sitting pretty.

But there are times when I look at her, at this very beautiful and very wealthy woman who happens to be my wife and who also happens to be an addict. I look at her and I remember the woman she used to be, the free and independent one. I remember the first night on the beach, and I remember other nights and other places, and I know that something is gone forever. She is not alive in quite the same way now. The face is the same and the body is the same but something has changed. The eyes, maybe. Or the deep darkness behind them.

The bird in your cage is not the same bird as the wild thing you caught in the forest. There is a difference.

So many things could happen. Some fine day the big man could disappear forever from the café. She’d be a deep-sea diver with her air-hose cut, and we’d burrow through Vegas turning over flat stones to find a connection, and I would have the rare privilege of watching Mona die inside. By inches.

Or a raid, and cold turkey behind bars, banging her head against the walls and screaming sandpaper curses at the guards. Or an overdose because some idiot somewhere in the long powdery chain forgot to cut the heroin when it was his turn. An overdose, with her veins blue and her eyes bulging and death there before she gets the needle out of her arm.

So many things—

I think she’s happy now. Once she got used to being addicted—how do you get used to addiction? A good question—once she got used to it, she began to enjoy it. Strange but true. When you have an itch you enjoy scratching it. Now she looks forward to her shots, takes pleasure in them. A certain amount of reality is lost, of course. But she seems to think that what she gets in its place more than compensates for reality. She may be right. The real world is often vastly overrated.

Strange.

“You should try it,” she’ll say now and then. “I wish I could tell you what it’s like. It’s really something. Like a bomb going off, you dig?”

She retreats into hip talk when she gets high.

“You should make it, Joe. Just one little joy-bomb to get you moving. So you can see what it’s like.”

A strange life in a strange world.

A funny thing happened yesterday.

I was giving her her four

P.M.

fix. I cooked the heroin, sucked it up in the hypo, picked up her leg and hunted around for the vein. She was just at the point where she needed the shot and in another five or ten minutes she would have started to shake. I found the vein and fixed her and watched the graceful smile spread on her face before she went under.

Then I was washing the spoon, getting ready to put the kit away. Some junkies don’t take good care of their equipment. They die of infection that way. I’m always careful.

I was washing the spoon, as I said, and then I was putting it away. I stopped—maybe I should say I slowed down—and then I was picking up another little capsule filled with funny white powder, putting it on the spoon.

I wanted to take a shot myself.

Silly. Her words hadn’t done it, her invitations to find out what it was all about. I wasn’t a kid looking for kicks.

So naturally I put the cap away. And I put the spoon away and put the syringe away. I locked up the kit and the bag of capsules. Even in Vegas you never know when some cop is going to decide his arrest quota is off for the month. I never leave things lying around.

I put everything away.

For the time being.

And I’ve been thinking about it ever since. I have a damned good idea what is going to happen. It may be the next time I give her a shot, or a week from then, or a month. She’ll slip away from me, with the same grateful smile fading slowly on the same sad and lovely face, and I will begin to wash the works.

Then I’ll take a shot of my own.

Not for kicks or thrills or joy. Not for pleasure or escape, not as a reward and not as penance. Not because I crave the life of a junkie. I don’t.

Something else. To share with her, maybe. Or maybe the nagging knowledge that every time the heroin takes hold of her she slips that much further away from me. Something like that, I don’t know. But one of these days or weeks or months I’ll take that shot for myself.

I think we’re going to be very something together. Whatever it is, at least it will be together. And that’s what I wanted, isn’t it?

This turned out to be the first book published under my own name, although I assumed it would be pseudonymous soft-core porn when I started it. A couple of chapters in I decided that this book might be a cut above what I’d been writing, so I wrote it as a crime novel with the hope it might work for Gold Medal Books. They were the first house to see it, and Knox Burger bought it. I can’t recall that he asked for any changes.

But they changed the title. I’d called it

The Girl on the Beach

, because that was such a Charles Williams / Gil Brewer / Peter Rabe title, perfect for Gold Medal. Knox didn’t like it. Go figure. Then somebody, he or I or my agent, came up with

Grifter's Game

, and that was one everybody liked.

Next thing I knew, it was published as

Mona

. Years later I learned from Knox that this was publisher Ralph Daigh’s idea. He’d bought a painting of a woman’s face from an illustrator and wanted a chance to use it on something. If he’d used a portrait of himself, I might be the author of

Horse’s Ass

.

The book has had various titles over the years. Someone used the phrase “sweet slow death” in a cover blurb, and Berkley made

that

the title on their reprint edition. When Hard Case Crime brought out the book a couple of years ago, we finally got to call it

Grifter's Game

.

Going over the story prior to ebook publication, I found it remarkable how many of the book’s fifty thousand words seem to be devoted to the lighting, smoking, and stubbing out of cigarettes. I’m surprised lung cancer didn’t take Joe Marlin out of the picture before the plot had run its course. I noticed, too, that I always used the word “lighted.” As in “I lighted a cigarette.” Do people talk that way? I never did, so why should Joe Marlin? I changed all those instances of

lighted

to

lit

. And I couldn’t resist the chance to fix the occasional infelicitous phrase here and there.

But I didn’t do much to it. The book was written in 1960 in a small apartment on West Sixty-Ninth Street between Columbus and Amsterdam avenues. I’d moved to 444 Central Park West by the time it came out in 1961. The fact that it’s still around strikes me as remarkable, but then I’m still around, too, and that’s no less remarkable. Here’s to both of us!

—Lawrence Block

Greenwich Village

Lawrence Block ([email protected]) welcomes your email responses; he reads them all, and replies when he can.

Lawrence Block (b. 1938) is the recipient of a Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America and an internationally renowned bestselling author. His prolific career spans over one hundred books, including four bestselling series as well as dozens of short stories, articles, and books on writing. He has won four Edgar and Shamus Awards, two Falcon Awards from the Maltese Falcon Society of Japan, the Nero and Philip Marlowe Awards, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Private Eye Writers of America, and the Cartier Diamond Dagger from the Crime Writers Association of the United Kingdom. In France, he has been awarded the title Grand Maitre du Roman Noir and has twice received the Societe 813 trophy.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Block attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Leaving school before graduation, he moved to New York City, a locale that features prominently in most of his works. His earliest published writing appeared in the 1950s, frequently under pseudonyms, and many of these novels are now considered classics of the pulp fiction genre. During his early writing years, Block also worked in the mailroom of a publishing house and reviewed the submission slush pile for a literary agency. He has cited the latter experience as a valuable lesson for a beginning writer.

Block’s first short story, “You Can’t Lose,” was published in 1957 in

Manhunt

, the first of dozens of short stories and articles that he would publish over the years in publications including

American Heritage

,

Redbook

,

Playboy

,

Cosmopolitan

,

GQ

, and the

New York Times

. His short fiction has been featured and reprinted in over eleven collections including

Enough Rope

(2002), which is comprised of eighty-four of his short stories.

In 1966, Block introduced the insomniac protagonist Evan Tanner in the novel

The Thief Who Couldn’t Sleep

. Block’s diverse heroes also include the urbane and witty bookseller—and thief-on-the-side—Bernie Rhodenbarr; the gritty recovering alcoholic and private investigator Matthew Scudder; and Chip Harrison, the comical assistant to a private investigator with a Nero Wolfe fixation who appears in

No Score

,

Chip Harrison Scores Again

,

Make Out with Murder

, and

The Topless Tulip Caper

. Block has also written several short stories and novels featuring Keller, a professional hit man. Block’s work is praised for his richly imagined and varied characters and frequent use of humor.

A father of three daughters, Block lives in New York City with his second wife, Lynne. When he isn’t touring or attending mystery conventions, he and Lynne are frequent travelers, as members of the Travelers’ Century Club for nearly a decade now, and have visited about 150 countries.

A four-year-old Block in 1942.

Block during the summer of 1944, with his baby sister, Betsy.

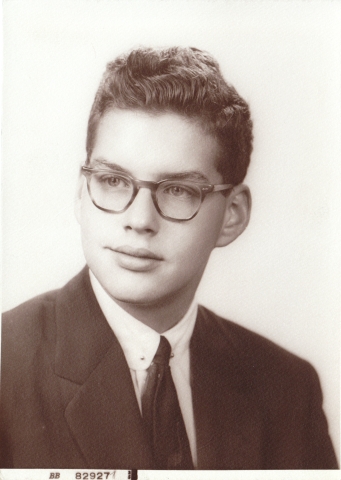

Block’s 1955 yearbook picture from Bennett High School in Buffalo, New York.

Block in 1983, in a cap and leather jacket. Block says that he “later lost the cap, and some son of a bitch stole the jacket. Don’t even ask about the hair.”