Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (41 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

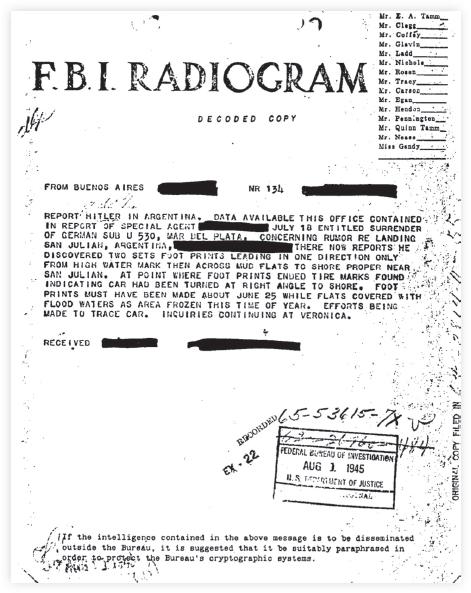

FBI REPORT RECORDED in August 1945, substantiated in Argentine police files, of the landings at Necochea and the support system awaiting Hitler.

ANOTHER SAILOR

from the

Admiral Graf Spee

also had recollections of the landing.

Petty Officer Heinrich Bethe

, whose later role in Hitler’s life is discussed at length in

Chapter 23

, was interviewed by one

Capt. Manuel Monasterio

in 1977, when Bethe was living in the Patagonian coastal town of Caleta Olivia under the pseudonym Pablo Glocknick (he was also known as Juan Paulovsky). Bethe had repaired Monasterio’s car one day after it had broken down. The captain and the former Kriegsmarine petty officer immediately hit it off, and on a number of occasions over bottles of wine and local seafood, the former sailor recounted his time as Hitler’s companion in exile. Bethe said he had escaped the clutches of the Bormann organization after Hitler’s death in Argentina and had lived in obscurity on the coast, working as an occasional mechanic, his trade aboard the

Admiral Graf Spee.

Petty Officer

Bethe’s recollections of the U-boat landings

are essentially similar to those of

Schultz, Dettelmann, and Brennecke

, but his description of the location of the landing site differs substantially (see

map

). Bethe spoke of a landing area “several hours” of driving over rough roads from the city of Puerto Madryn, which is much further south than Necochea. Bethe recalled that on the evening of July 28, he directed trucks to a determined point on the coast and from there proceeded to load a large number of boxes that came ashore on rubber dinghies from two submarines. The trucks carried the boxes to two large depositories where they were carefully unloaded. Later, about seventy people disembarked from the U-boat. In Bethe’s opinion, “the cargo was very valuable, and the people that arrived were not common sailors like [himself], but presumably hierarchy of the Third Reich.”

The two accounts may seem to describe the same landing, but there were in fact two such missions: one at Necochea that delivered Hitler, and one further south that unloaded the loot to finance his future.

Ingeborg Schaeffer

, the wife of First Lt. Heinz Schaeffer, commander of U-977, which surrendered at Mar del Plata on August 17, 1945, was asked in 2008 if her husband had brought Hitler to Argentina. Mrs. Schaeffer replied, “If he did not bring him, there were another two U-boats that could have brought him, and [my husband] could have given them food and so forth, because the others went on to Puerto Madryn.” Although her comments are somewhat cryptic, she was obviously aware of other Nazi submarines in Argentine waters at the same time as U-977, information she could have got only from her husband. Schaeffer’s U-977 was a Type VIIC from U-Flotille 31. The Allies had believed that Argentina was beyond the range of this smaller class of U-boat, but the fact remains that Schaeffer reached Mar del Plata. However, Puerto Madryn was indeed beyond his range unless he stopped to refuel, as it was more than 500 miles away as the crow flies and much more following the coastline. Ingeborg Schaeffer’s testimony, and other evidence from Argentine navy documents, clearly point to two separate groups of U-boats.

One pair was U-880, which likely passed Fegelein over to a tug off Mar del Plata on July 23, and U-518, which is believed to have landed Hitler at Necochea on July 28. Both of these were Type IXC boats from U-Flotille 33, large enough to carry passengers and cargo (as also were U-530 and U-1235).

A separate group included U-530, which First Lt. Otto Wermuth surrendered at Mar del Plata on July 10—two weeks ahead of the boat that brought Hitler. This boat was in terrible condition and contained nothing of value; it may already have offloaded cargo at Necochea for Estancia Moromar.

Wermuth’s interrogation report

—translated from German into Spanish, and finally into English by the U.S. Navy—says that he considered landing at “Miromar” before deciding to surrender at Mar del Plata. He said that he had left Kristiansand on March 3, 1945, and proceeded to Horten in Oslo Fjord, Norway, where for some reason “not stated” he remained for two days (possibly to load cargo). U-530 had no torpedoes, weapons, or ammunition on board; by contrast, U-977 was carrying its full complement of weapons and torpedoes when it surrendered on August 17—a full five weeks after U-530. Wermuth’s mention of “Miromar,” and the fact that getting rid of the torpedoes would have provided space for clandestine cargo, suggest that he may have had something to hide from his interrogators. He refused to say whether or not U-530 was alone, but he did say that he operated under direct orders from Berlin and that the last direct contact he had was on April 26. Wermuth said that he did not know of any other submarines headed for Argentina, but that if any more were coming, they would arrive

within a week of his own arrival

.

REPORT FROM FBI in Buenos Aires recorded in August 1945, concerning arrivals in Argentina by U-boat.

INGEBORG SCHAEFFER’S TESTIMONY

suggests that a second group of boats, responsible for the landings near Puerto Madryn described by Heinrich Bethe, might have been escorted by her husband’s fully armed U-977, which left Kristiansand on May 2, 1945—the day before U-530 sailed. Both U-530, and U-1235 from Gruppe Seewolf, had the range for the southernmost landings. The presence of a second group of three boats is also suggested in two separate

television interviews conducted in Buenos Aires with Wilfred von Oven

. Oven was the personal press adjutant to Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels between 1943 and 1945. He had accompanied the Condor Legion in Spain as a war correspondent and was acquainted with Gen. Wilhelm von Faupel of the Ibero-American Institute. Oven went into hiding in 1945 under an assumed name and fled to Argentina in 1951; a committed Nazi, he was declared persona non grata by the Federal German Embassy in Buenos Aires. Before he died in 2008, Oven was asked about a “fleet” of Nazi submarines coming to Argentina in 1945. On two occasions—once to an Argentine author, and again to a British TV crew—he replied, in what appeared to be almost a conversational slip, “No, there were only three, just three.” His interviews are rambling and given in an arch manner suggesting that he knew more than he was willing to tell, but on the matter of the three U-boats he seemed quite lucid.

An

Argentine government memorandum

of October 14, 1952, stated:

I bring to your attention that our agents [names deleted] have detected at Ascochinga, in the mountainous region of Córdoba province, a farm located on the Cerro Negro, which has been acquired by a former officer who disembarked from U-235 [sic] at the Mar del Plata naval base. This boat, together with other German submarines, came to Patagonia from Germany after the conclusion of hostilities.

The Canadian author William Stevenson also mentions a U-235:

It was reported that members of the brotherhood began to quarrel over money during the 1960s, and this seemed probably true. The leader of the rebellion against Bormann was

described as the commander of U-235

. He was said to have brought his vessel to Argentine waters, discharged a cargo of stolen Nazi treasures, scuttled the U-boat, converted the cargo to money and bought a large estate.

Confusion in these sources between the numbers U-235 and U-1235 seems quite plausible. It is certain that the real U-235, a Type VIIC, was

lost with all hands

in the Kattegat Bay area off the Danish coast on April 14, 1945, to a depth-charge attack in error by German S-boat T-17. There is no official record of a third boat in addition to U-530 and U-977—which might have been U-1235—surrendering to the Argentine authorities at Mar del Plata. However, on July 19, 1945, the Buenos Aires daily newspaper

Critica

reported that yet another U-boat had been “surrounded by Argentine Navy vessels thirty miles off the coast of Mar del Ajo” just north of Mar del Plata. Nothing more is ever heard of this boat.

The question of what happened to the crews that landed from those U-boats that were scuttled rather than surrendering—potentially, U-518, U-880, and U-1235—naturally arises. Despite the story that the commander of what was probably U-1235 (

Lt. Cdr. Franz Barsch

) survived to buy a farm in Córdoba, where he was still living in 1952, there are no reports of any of the other submariners surfacing in Argentina after the war. The three boats together had a total of about 152 crewmen. The simplest answer is that it would have been perfectly possible to disperse these sailors among the hundreds of German communities scattered across Patagonia. It is possible to imagine that numbers of them might have preferred this prospect over a return to ruined, starving, occupied Germany, especially if their families had perished in the air raids or were now lost somewhere in the Soviet zone. A much more sinister alternative explanation is that they may have been disposed of shortly after their arrival. Nobody was looking for them in Argentina, after all, just as nobody was looking for Hitler, Eva Braun, Hermann Fegelein, or the masterminds of the entire escape plan, Martin Bormann and Heinrich “Gestapo” Müller. Bormann’s and Müller’s utter ruthlessness is beyond question; and Fegelein’s service in Russia had been spent commanding SS units employed in “antipartisan” warfare behind the fighting front.

IN 1945 THERE WAS NOTHING CONTROVERSIAL

about the idea that German submarines were operating clandestinely along the coast of Argentina. The possibilities were outlined

in a letter dated as early as August 7, 1939

, from Capt. Dietrich Niebuhr, the naval attaché at the Buenos Aires embassy, to his Berlin espionage controller Gen. von Faupel: “The strategic situation of the Patagonian and Tierra del Fuego coast lends itself marvelously to the installation of supply bases for [surface] raiders and submarines.” The Nazi-hunting Argentine congressman Silvano Santander had no doubts that such plans were carried out: “These [contact points] were established, and served to supply fuel to the German submarines and raiders. The Argentine government’s tolerance of this provoked numerous protests from the Allied governments. Later on, after the Nazi defeat, these bases were also used so that mysterious submarines could arrive, bringing both people and numerous valuables.” Allied intelligence services were aware of such possibilities from at least 1943, when the Americans began actively

seeking a secret U-boat

refueling and resupply base near the San Antonio lighthouse.

On May 22, 1945, after the end of the war with Germany, the Argentine foreign ministry informed the navy of “the presence of German submarine warships in the waters of the South Atlantic, trying to reach Japanese waters”; and on May 29, the

Argentine navy carried out antisubmarine operations

in the Strait of Magellan to prevent submarines passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This did not stop the traffic. The federal police reported that on July 1, 1945, two persons landed from a submarine near San Julián, on the Atlantic coast near the southern tip of Argentina and the Strait of Magellan. The two Germans paddled ashore

in a rubber boat

and were met by “a person who owned a sailboat.” The police said that the submarine was refueled from “drums hidden along the coast.” Such stories were nothing new. In January 1945,

Stanley Ross

, who had been a correspondent in Buenos Aires for the Overseas News Agency, reported that Nazi submarines had intensified their activities, bringing “millions of dollars in German war loot to this hemisphere to be cached here until the Nazi leaders could claim it.” Ross went on to write,

A Nazi submarine surfaced near the Argentine coast at Mar del Plata. It was seen to transfer to a tugboat of the Axis-owned Delfino line of Buenos Aires some forty boxes, and the person of Willi Koehn, chief of the Latin American Division of the German Foreign Ministry. While the submarine waited to take him back, Koehn, the former head of the Nazi Party in Chile, conferred in Buenos Aires with key Nazi agents and collaborationists.

By July 1945,

Koehn was already back

in Argentina, having joined Fegelein for U-880’s last voyage from Fuerteventura.

COL. RÓMULO BUSTOS COMMANDED

an Argentine coastal antiaircraft unit at Mar del Plata in the southern winter of 1945. In early June he was ordered by his superiors to cover a broad section of the coast between Mar del Plata and Mar Chiquita, to oppose any attempts by German U-boats to land and disembark; if anybody did disembark, he was to take as many prisoners as possible. “My group had to cover the area near Laguna Mar Chiquita, a few miles to the north of the naval base. We had nine cannons; we were ready to open fire. One dark night I saw light flashes from the sea to the coast, [directed] at a spot near the place where we were. I contacted the leader of our group. When he arrived at our position, the flashes had stopped,” but when the commander was about to leave, the flashes started again.