Great Maria (59 page)

Authors: Cecelia Holland

She paced around the room. On the wall near the head of the bed, there were thirty-eight short, deep scratches in the wall. She sat down and ran her fingertip over them. She wondered if Roger had made them, counting off the days. She lay down on the bed, her head in her arms, already bored. The afternoon crept along, dragging its shadow up the far wall.

A short knight brought her dinner; he came in without knocking first, and when he left she pulled the latch string inside the door, so that no one could get in without her will. She had no appetite for the meal he had brought her. She sat picking over it. The light faded out of the room. She had no lamp; she went to bed, but she could not sleep. A night bird sang just outside the window. The jarring uninflected ringing notes put her nerves on end. Finally, just before dawn, she dozed.

The knight woke her up, knocking on the door, but she ignored it. She lay staring at the scratches on the wall. Thirty-eight days. This was her second day in the treasure-house, and the twenty-third day of Lent. She would not miss Easter Mass; either she or Richard would give up by then.

She kept the latchstring tied inside the door. When noon came and the knock on her door signaled her lunch she ignored it again. She stood at the window, her arms folded on the sill. Deer grazed at the far end of the park. She longed for sight of her children, but sundown came without them. Morose, she let in the knight with her dinner.

That night she could not sleep again. She thought over and over of the baby who had died: its feeble mewling cry of hunger, while it vomited up everything it was fed. Once, deep in the night, she wept. The next morning she felt worse than ever before in her life. When the knight came in with her tray of breakfast she nearly sent him to Richard.

She could not eat. She sat on the bed and faced the scratches on the wall. Throughout the day she longed for death. She knew why Roger had gone so calmly out to die: the room was cursed.

In the evening, after she had forgotten to pull in the latchstring and they had brought her a supper she did not want, she began to pass blood. She felt bloated and exhausted, although she had done nothing for days. She felt the blood sign like a message: she should submit, she was a woman. She lay down on the bed and put her face into the pillow and cried until she fell asleep.

Morning came. She felt no better. She dragged herself into her clothes and stared out the window. When they knocked with her breakfast she did not let them in. The fallow deer grazed across the park. The little stag, darker than his does, strutted around wagging his tail. She missed Richard. She wanted Richard.

He was the only person who really knew what she was like; if her other friends had known all she had done, they would have hated her. She still had a ewer of wine left from the dinner they had given her the night before. She sat down and drank it, unwatered, until she was spinning drunk, and went to sleep. When she woke up, sick to her stomach, deep night had come and she had missed her supper.

She went to the window. Moonlight painted the grass and the wind-curried trees. She put her cheek against the cold stone. In the sky, the tiny cold fires of the stars burned: homes of angels. She could die here. He could keep her here for the rest of her life. For her children’s sake, she should surrender. She would, if Easter came. If she could not force him to come to her, she deserved no crown. That made her feel better, to think there was justice in it. She changed the blood-soaked rags between her legs and got back into bed.

The next day she took out her sewing baskets and began to mend her clothes. Often she went to the window to watch the deer and the sky and to look for her children. There was no sign at all of the children and she realized Richard was keeping them away from her. At sundown the knight knocked, and she let him in.

He put the food he carried down on the stool, as he usually did, and knelt to put the dishes of the previous meal back on their tray. Maria sat down on the bed. His back to her, he said, “Are you warm enough at night?”

“Yes. I’d like a lamp.”

“I’ll have to ask,” he said. He picked up the tray and left. She sat there savoring her first conversation in days. They did not bring her a lamp.

She began to lose her sense of time. When she had mended all of her clothes, she began to embroider them. At first she made flowers and birds but they bored her and she made up fantastic animals, dragons and basilisks, things with claws and wings and triple heads. When she ran out of thread she took apart the birds and flowers. She made up stories while she worked, about the beasts she stitched, the worlds they lived in, their remarkable qualities, and the heroes who fought them. Usually the beasts won. In the worlds where they lived there was no God.

***

She woke up in the dark. Someone was beating on the door. She sat up, pulling the blanket around her.

“Yes?”

“Maria,” Richard said, “let me in.”

She got up. She was naked, and she wrapped the blanket around her. The full moon glared in through the window and cast the shadow of the iron grid across the door. She opened the latch, and the door swung in.

“Put on your clothes. We’re going,” Richard said. He stood in the bright barred light.

She sat down on the foot of her bed. “You know what I want.”

He came into the darkness of the room, leaving the door half-open behind him. He went to the window, looked out, and turned around, his head and shoulders against the light. She watched him, wary, wishing she could see his face.

He said, querulous, “What’s wrong with this place? That stinking monk has everybody convinced you’re cooped into a barrel.”

“I don’t mind. It’s very peaceful. How long have I been here?”

“Seventeen days.”

She knew he was watching her. With the window behind him he was only a black shape to her. But he was here. Amazed, she realized that meant he was surrendering. She said, “When is Easter?”

“Tomorrow. If you and I don’t go to Mass together—”

He broke off. She said, “What?”

“I don’t know. I’m not ready to find out. Father Yvet wants the Pope to crown me. I want to put my own crown on my own head. You talk to him. Arrange that, and I’ll crown you with me.”

She drew a deep breath. “Yes.” She could do it; she already knew what argument to use. “I will.”

“Why are you doing this?”

She said, “If you could rule without me, you wouldn’t be here.”

“Put on your clothes.”

In the dark she pulled on a shift and a gown and groped around the floor for her shoes. They went down the steep steps and across the treasure room, and he knocked on the door. Torches burned around the treasure room. The chests and boxes were covered with dust and smeared with handprints. They went on into the antechamber. Three knights stood there, their faces yellowed in the lamplight. Richard went straight out the door.

Maria stopped on the threshold. Off across the half mile of grass lay the back wall of the palace and the round of the Dragon Tower. Richard was already halfway down the path. One of the knights behind her said loudly, “If she were mine, she’d never get out.”

She turned around. The three men shuffled and looked away. “Roussel,” she said to the tall knight. “Bring my chest back to the palace.”

“Yes, Madonna.”

She went out the door onto the sodden grass. The moon was sinking. Along the eastern edge of the sky, dawn light whitened. She admired him for having waited as long as he could: the Mass began at sunrise. She would hardly have time enough to change her clothes.

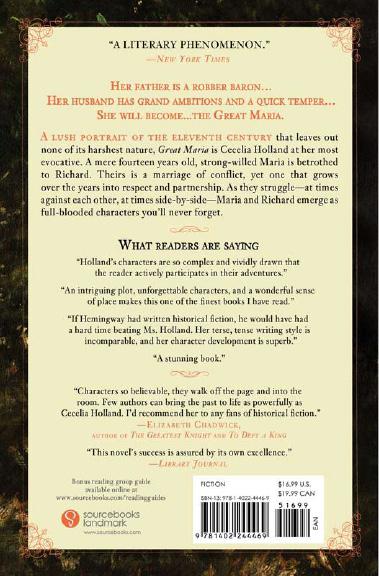

About the Author

Cecelia Holland was born in 1943 and has written twenty-four historical novels, the first of which was published in 1966. The

New York Times

has called her a “literary phenomenon.” She attended Connecticut College and now lives in northern California.