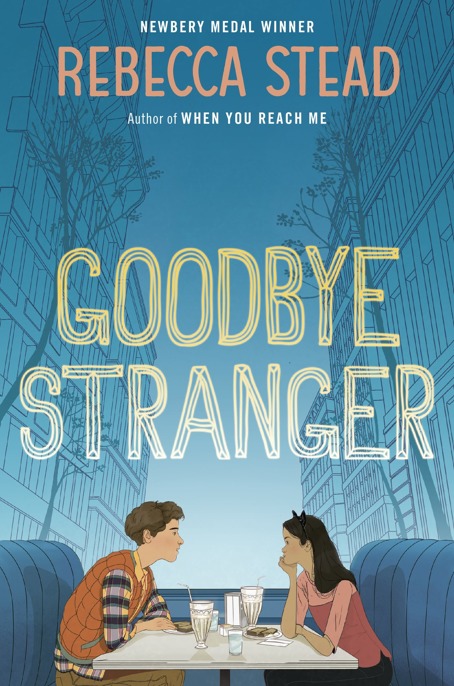

Goodbye Stranger

Authors: Rebecca Stead

ALSO BY REBECCA STEAD

Liar & Spy

When You Reach Me

First Light

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2015 by Rebecca Stead

Cover art copyright © 2015 by Marcos Chin

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Wendy Lamb Books, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Wendy Lamb Books and the colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhousekids.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stead, Rebecca.

Goodbye stranger / Rebecca Stead. — First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-385-74317-4 (trade) — ISBN 978-0-375-99098-4 (lib. bdg.) — ISBN 978-0-307-98085-4 (ebook) — ISBN 978-0-307-98086-1 (pbk.) [1. Best friends—Fiction. 2. Friendship—Fiction. 3. Middle schools—Fiction. 4. Schools—Fiction. 5. Family life—New York (State)—New York—Fiction. 6. New York (N.Y.)—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.S80857Goo 2015

[Fic]—dc23

2014037289

eBook ISBN 9780307980854

Cover design by Kate Gartner and Katrina Damkoehler

eBook design adapted from printed book design by Stephanie Moss

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v4.1

ep

Contents

The Pitfalls of Being Wonder Woman

The Second Definition of Permission

For my friends,

including the one I married

PROLOGUE

When she was eight years old, Bridget Barsamian woke up in a hospital, where a doctor told her she shouldn’t be alive. It’s possible that he was complimenting her heart’s determination to keep pumping when half her blood was still uptown on 114th Street, but more likely he was scolding her for roller-skating into traffic the way she had.

Despite what it looked like, she

had

been paying attention—she saw the red light ahead, and the cars. She merely failed to realize how quickly she was approaching them. Her skates had a way of making her feel powerful and relaxed, and it was easy to lose track of her speed.

When she was eight, Bridget loved two things: Charlie Chaplin and VW Bugs. She practiced her Chaplin moves whenever she could—his funny duckwalk and the casually choppy way he zoomed around on his skates, arms straight down, legs swinging.

Her interest in Volkswagen Bugs was less aesthetic. Whenever she saw one, she shouted, “Bug-buggy, ZOO-buggy!” which entitled her to punch whoever she happened to be with, twice, on the arm.

She saw the red light and the traffic that afternoon, but she also saw a yellow VW Bug double-parked near a fire hydrant. So, still hurtling toward Broadway, she turned her head to yell “Bug-buggy, ZOO-buggy!” at her friend Tabitha, who was on a scooter right behind her. She wanted to be sure Tabitha heard her loud and clear, because she intended to hit her on the arm, twice, when they stopped at the corner, and didn’t want any arguments.

“Bug-buggy, ZOO-buggy!” she shouted.

But Tabitha had fallen behind. “WHAT?” Tabitha called back.

So Bridget started again. “BUG—” And she flew straight past the corner into the street, a Chaplin move if there ever was one, accompanied by the high music of two screaming mothers—her own and Tabitha’s—from somewhere far behind.

—

She missed third grade, but her body repaired itself. After four surgeries and a year of physical therapy, she showed no sign of injury. But Bridget was different, after: she froze sometimes when she was about to cross the street, both legs locked against her will, and she had a recurring nightmare that she’d been wrapped head to toe like a mummy, from which she always woke with a sucking breath, kicking at her covers.

The nightmares began when she was still in the hospital. In those days, which stretched into weeks, her mother sometimes brought her cello and played quietly at the foot of Bridget’s bed. Sometimes her mother’s music drew designs behind Bridget’s closed eyelids. Sometimes it put her to sleep. One afternoon, Bridge woke to the sound of her mother’s cello and said loudly, “I want to be called Bridge after this. I don’t feel like Bridget anymore.” Still playing, her mother nodded, and Bridge went back to sleep.

There was one other thing. On the day Bridge was discharged from the hospital, one of the nurses said something that changed the way she thought about herself. The nurse said, “Thirteen broken bones and a punctured lung. You must have been put on this earth for a reason, little girl, to have survived.”

It was a nicer, more interesting way of saying what the doctor had told her when she first woke up after the accident. Bridge couldn’t answer the nurse, because by that time her jaw had been wired shut. Otherwise, she might have asked, “What

is

the reason?” Instead, the question stayed in her head, where it circled.

THE CAT EARS

Bridge started wearing the cat ears in September, on the third Monday of seventh grade.

The cat ears were black, on a black headband. Not exactly the color of her hair, but close. Checking her reflection in the back of her cereal spoon, she thought they looked surprisingly natural.

On the table in front of her was a wrinkled sheet of homework. It wasn’t homework yet, actually. Aside from her name, the paper was blank. She itched to draw a small, round Martian in the upper left-hand corner.

Instead, she put down the spoon, picked up her pen, and wrote:

What is love?

This was her assignment: answer the question “What is love?”

In full sentences.

She looked at the empty blue lines on the page and tried to imagine them full of words.

Love is __________.

Her mom had once told her that love was a kind of music. One day, you could just…hear it.

“Was it like that when you met Dad?” Bridge had asked. “Like hearing music for the first time?”

“Oh, I heard the music before that,” her mom had said. “And I danced with a few people before I met Daddy. But when I found him, I knew I had a dance partner for life.”

But Bridge couldn’t write that. And anyway, her mom was a cellist. Everything was about music to her.

Bridge squeezed her eyes closed until she saw glittery things floating in the dark. Then she started writing, quickly.

Love is when you like someone so much that you can’t just call it “like,” so you have to call it “love.”

It was only one sentence, but she was out of time.

—

Bridge had noticed the cat ears earlier that morning, on the shelf above her desk, where they’d been sitting since the previous Halloween. They felt strange at first, and made the sides of her head throb a tiny bit when she chewed her cereal, but as she walked toward school, the ears became a comforting presence. When she was small, her father would sometimes rest his hand on her head as they went down the street. It was a little bit like that.

Bridge stopped just outside the front doors of her school, slipped her phone out of her pocket, and texted her mom:

At school.

XOXO

, her mom texted back.

Bridge’s mother was on an Amtrak train, coming home from a performance in Boston with her string quartet. Bridge’s father, who owned a coffee place a few blocks from their apartment, had to be at the store by seven a.m. And her brother, Jamie, left early for high school. His subway ride was almost an hour long.

So there had been no one at home that morning to make her think twice about the cat ears. Not that anyone in her family was the type to try to stop her from wearing them in the first place. And not that she was the type to

be

stopped.

—

Tabitha was next to Bridge’s locker, waiting. “Hurry up, the bell’s about to ring.”

“Okay.” Bridge faced her locker and puckered up. “One, two…” She leaned in and kissed the skinny metal door.

“Nice one. You can stop doing that anytime, you know.”

Bridge spun her lock and jerked the door open. “Not until the end of the month.” Seventh grade was the year they finally got to have lockers, and Bridge swore she was going to kiss hers every day until the end of September.

“You have ears,” Tab said. “Extra ones, I mean.”

“Yeah.” Bridge put both hands up and touched the rounded tips of her cat ears. “Soft.”

“They’re sweet. You gonna wear them all day?”

“Maybe.” Madame Lawrence might make her take them off, she knew. But Bridge didn’t have French on Mondays.