Good Things I Wish You (6 page)

Read Good Things I Wish You Online

Authors: Manette Ansay

He was speaking to me as my teacher, of course, but also as a friend.

“A little bit of lipstick never hurt a girl,” he said. “Not that I’m suggesting you should paint yourself like one of Herr Brahms’s whores.”

He apologized for his language. He only wanted what was best. He was trying to protect me, the way Clara’s father tried to protect her, but did Clara listen? Did she? Could I understand how much Clara’s father had loved her, how he would have done anything to save her from the life she lived with Schumann, reduced to a common hausfrau, wiping the mouths and asses of brats? I must find a man who would be prepared to offer everything, but only from a distance. A man who would look out for me. Who would ask almost nothing in return.

Kissing my fingers, untucking my shirt.

How can you play if you can’t lift your arms?

We were at it again, two hands, four. The room echoed with our longing. Still, I wouldn’t let him hold me. In the end, I’d always get up, step away.

For art is about desire, is it not, and never its consummation?

“I am beginning to think,” the piano teacher said, “that you are incapable of passion.”

12.

F

OR SEVERAL YEARS, THERE

was a man who was in love with me. L—had gotten divorced after discovering a cache of e-mails from his wife’s lover, and he’d call me (not too often, of course, for I was married to Cal) just to see how I was doing, talk about books, exchange manuscripts-in-progress. We’d talk about love and relationships, marriage and friendship, true friendship between women and men, which we both agreed was absolutely possible, why not? Not only possible. Necessary. At a literary conference, drunk on wine and success, I told him about Cal, our separate rooms, our separate lives. L—followed me up to my hotel room…

…where I left him standing outside the door.

All night long, my chest and belly ached with what I thought was virtue.

“I don’t see how you can stand it,” he said the next time we spoke.

The last time.

“It’s not so bad,” I said.

“Then something’s wrong with you,” he said, and I hung up on him.

Shortly after my divorce, I heard from him again, a brief e-mail in which he said he’d been sorry to hear about Cal and me. He’d recently remarried, someone we both knew, a woman who writes about horses. She, too, he said, was thinking of me, would keep me in her thoughts. Both of them had been through it themselves. Both of them knew how tough it could be. So how was I doing? Probably okay. But I shouldn’t hesitate to drop him a line if I ever needed a listening ear.

13.

“G

OING THROUGH A DIVORCE,

” Ellen had said as we’d carried Cal’s boxes out to the garage, “is like going through chemotherapy. You have to expect to get really, really sick. The difference with divorce is that you know you are going to get better.”

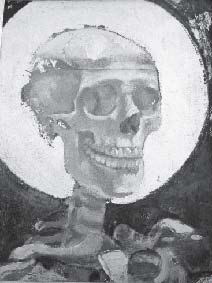

Self-Portrait: Gaela Erwin

*

Frozen

14.

T

HE SECOND TIME I

experienced déjà vu, Heidi was two years old. It was October, a Thursday morning. I’d just started at the university, teaching classes on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. Each Tuesday, I made the six-hour round-trip commute from West Palm Beach, arriving home just in time to tuck Heidi in for the night. On Wednesday nights, however, I’d stay over in Miami. I’d check into my hotel room by six

P.M

. I’d write until one or two in the morning, sleep in until eight the next day, when I’d start to prep my graduate seminar.

This was the longest block of writing time I’d had since Heidi’s birth.

That morning, just as I’d been packing up my computer, I’d received a call from my mother. Cal wasn’t working at the time. He’d resigned a full-time contract on the promise of another job that, in the end, hadn’t worked out, but we were trying to look on the bright side. He’d been thinking about getting out of teaching anyway. He was thinking about earning a Ph.D. He was supposed to be researching programs, studying for the GRE, but the reality was that

he was stuck, not certain what he wanted to do next. If we could have talked about it—but we couldn’t talk about it. The trick to getting along seemed to be avoiding talk altogether. I worked and wrote and took care of Heidi. He read the news on the Internet, blogged with reenactment friends.

Of course he took care of Heidi on the days I was at work.

“You don’t give Cal a chance with that baby,” friends and family members said. “Get out of the house. Get out of his way. Let the two of them get to know each other.”

I believed them because I wanted to believe them.

I believed them because I waited all week for that single night, alone at my computer, in room 342 at the Holiday Inn.

“I don’t want to worry you,” my mother said. “But yesterday, Cal and Heidi came over, and Heidi threw up on her shirt. I offered to wash it, but he said no, he’d take care of it when they got home.”

“Is she sick?” I said.

“I think she’s fine,” my mother said. “But this morning, when I stopped by to see if she was feeling better, she was still wearing the same shirt.”

“Maybe it’s just that he couldn’t get the stain—”

“She stank to high heaven, Jeanie,” my mother said. “And Calvin looks—well, he hasn’t changed his clothes since yesterday, either. It’s more than a hangover, Jeanie. He’s not in a good state of mind.”

What I should have said: “I’ll be home on the next train.”

What I said: “I’ve got to teach in an hour.”

My mother did not say anything.

“You can’t just cancel a graduate-level class.”

My mother said, “You know what you can and cannot do.”

Now, nursing a Starbucks cappuccino, I was standing at the corner of Ponce and Dixie, preparing to dash across the four-lane highway, as I did every day, to get to campus. Hurricanes had knocked out the pedestrian walk signs, so you had to time the lights, gauge the speed of the on-coming traffic, which tended to accelerate—Miami being Miami—at the sight of a human being actually braving a crosswalk. During the first week of classes, at exactly this spot, a student had been hit by a car and killed. I thought of her today, as I always did, reminding myself to be careful.

High overhead, a half-dozen vultures circled aimlessly.

Perhaps Heidi had insisted on that particular shirt and Cal simply hadn’t had the energy to deal with it. Perhaps she was sick, had been sick all night long, and that’s why Cal was in the same clothes: he’d spent a sleepless night caring for her. None of this rang true, but I didn’t want to think about what it meant. By

what it meant,

I did not mean what it meant for Heidi or, for that matter, Cal. I was thinking about my writing. I was thinking about myself. I was thinking about what it would mean to lose those Wednesday nights, and I thought to myself, in exactly these words: “I am a dead woman. I am dead.”

The light changed. There was a gap in the traffic. I decided to run for the median, wait for a second opportunity

to cross the remaining lanes. But as soon as I stepped up onto the narrow concrete strip, I could see exactly what would happen next. Even before I dropped my cappuccino, I knew how it would bounce, still capped, into the oncoming traffic. Even before my left ankle buckled, I knew how my body would feel as it fell, the impact of my hip, vibrations rising through the concrete. The car that would strike me already gaining speed. The steely flash of fender in the split second before, in an attempt to twist away, I’d make things worse by rolling directly into the path of the wheel.

The traffic lights changed. Changed again. I stood, frozen, on the median. How long was I waiting there before a group of students came along? One of them doubled back.

Are you okay? You want to cross with us?

As long as I remained there, the future could not reach me.

Do you want to take my arm?

Even now, I can re-create the feeling of that car striking me as if it really happened, though in fact it never did.

15.

T

HE NIGHT BEFORE THE

suicide attempt was the first time Clara hadn’t shared his bed. Sheets wet with sour perspiration. Bruises, the size and shape of kisses, dotting her upper arms. Another bruise on the small of her back from the unexpected bucking of his knee. That was the thing that did it. Not that she would ever blame Robert for what he’d done. Hour after hour, the dead were tormenting him, singing the same three notes while he thrashed like a man in physical pain. At last he’d lulled into stillness. She, too, slept for a while—until awakened by the impact of the floor.

“Stay away from me,” he was shouting. “I will hurt you! I will kill you! How can you bear it?”

And she looked up at his frenzied face peering down at what he’d done—fat-cheeked, demonic—and answered, “I cannot.”

“Why not fetch your maid to sit with me?” he’d said, suddenly cogent, calm. So she’d kissed his damp hand and done as he had said, crawling into bed beside Marie, where she slept six uninterrupted hours before awakening to the sound of the milk cart. Marie was already gone. A faint, greasy light filtered in beneath the door, seeped

through the rift in the curtains. Downstairs, the cook battled the coal stove. The clop of the milk cart continued on. Everything normal. Everything calm. For a moment, a thought came into her mind, accompanied by guilt as sharp as pleasure. But then she heard him talking, heard the maid’s stout reply.

The door opened. Marie, fully dressed.

“Papa is better, I think,” she said.

Time, once again, to get out of bed. To step forward into the day. Robert already seated at table, fumbling his napkin beneath his great, soft chin. Clara directs the children toward eggs set in cups, toward bowls filled with porridge and cream. She eats. Smiles. Performs. As she’s been performing since the age of nine, through broken pianos and cholera epidemics, through her father’s rages and her husband’s jealousies, through cities and countries and continents not nearly as far-flung as she’d hoped. Even in good health Robert requires just this: familiarity, routine. A house in which children sit in their places. Orderly servants. Clean windows and halls. A room of his own where he keeps his piano, books, compositions, poetry, reviews. Glasses of sweet, dark beer at the pub during the hour or two before supper each night when she closes the door against children and staff, practicing hastily, hungrily.

Later he’ll wrap his arms around her with the same quick, anxious greed.

So she’s come to be pregnant with his eighth child. And to anyone here in the twenty-first century who might object to the phrase “his child,” who suggests that these children

belong to them both, she’ll insist—urgently, fiercely—that the children, like everything else, belong only to her husband. As the concerts she has performed, the money she has earned, the lessons she has taught belong to him. The few compositions she’s managed during her fourteen years of marriage? These belong to him as well. If she could, she’d drain the very blood from her body. She’d feed it to him as she feeds broth to the little ones, trembling at the lip of the spoon.

The only thing she has kept for herself: her desire to play music in public, to perform. Since it’s all that she has kept, it’s the one thing he wants. Day after day, it sits between them. The single thing she’s held back.

But today, as he smiles across from her, the children encircling them both with bright laughter, it seems possible that everything she’s offered, everything she’s given, will suffice. Perhaps Marie is right this time. Perhaps Papa is truly better. Clara is looking directly at him—a look in which everything good must shine—when he says, “Forget about me, Clara. I am not worthy of your love.”

The words hit her like a slap.

Forget about me. Forget about us. Forget about all we have meant to each other.

He said that,

she will write in her diary,

he to whom I had always looked up with the greatest, deepest reverence.

*