Good Things I Wish You (19 page)

Read Good Things I Wish You Online

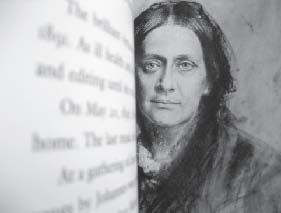

Authors: Manette Ansay

Even now, this heat does not break.

Another gate. Cows like pale boulders.

A fence. The first stand of trees.

More trees, and now woods, moon dappled, fragrant, where she guides him toward a platform she and the boys found yesterday, placing their feet in the ax-hewn steps, hauling themselves up into the cooling leaves. For a moment it seems they can both believe this discovery is why she has led them here. Johannes is delighted. He shimmies up the tree trunk to the platform, then continues to climb, working his way from branch to branch, his dressing gown sending showers of snagged twigs and leaves upon Clara’s head. Even after stopping to knot her gown, she must struggle to climb each step. She is a woman. She is no longer young. When she reaches the platform, she sprawls on her back.

“Johannes?” she calls, but he does not come down.

Hart was reading, the way he did read: silently, rapidly, utterly absorbed. I held the anthology open on my stomach. I watched the cherub, who watched me back.

“Johannes?”

She holds her breath, listening. Though she can’t hear him, can’t see him, she knows he is just above, listening too. Suddenly, wildly, he drops onto the platform; she gasps as the boards shake beneath them, and then he is laughing, she is scolding, they are both themselves again. So much themselves that it seems, at first, that their hands on each other, their mouths on each other, are just a continuation of another conversation, more of the music they make together so easily, so effortlessly, only now everything between them turns strange, his breath like a curse, a hiss, a howl, and it’s nothing like what she remembers of tenderness, over almost before it’s begun.

His gaze on her is a stranger’s gaze: terrible and cold.

“What is it? What is the matter?” she says.

He thrusts her away with such force that she nearly tumbles from the platform’s edge.

She leaves him there, stumbling down through the trees, across the pasture and along the rocky path toward the garden gate, which she passes, and the church, which she passes, and the little road fronting the water, which she crosses, and then she is standing at the edge of the lake. Up to her ankles. Up to her knees. The moon lighting up her shimmering reflection. Angular body. Strong-featured face. She thinks, as she’s often thought before, that if only she’d been prettier, more feminine, everything would have been different. If only she’d been less gifted, less determined, less strong. What happened just now serves only to confirm this.

What happened to Robert was her fault.

“Was there really a tree house and a platform?” Hart asked. The clock in the corner of my laptop screen said

2

A.M

. “Did she really walk out into the water that way?”

“I made up everything in that scene.”

“The way you made things up about us.”

“But it

isn’t

us. That’s what I’m trying to say.”

“Isn’t it?” He rubbed his eyes, and when he looked at me again, I saw the white-coated scientist in his lab, the man I’d first met at the Wine Cellar. “The scene is effective,” he said, “because it plays a trick on the reader. We are not expecting she’ll be thinking of her husband. I myself had not thought about this before. But I believe you are right about how she felt.”

That heat: pressing down like a smothering hand.

“It is the same way, I suppose,” Hart said, still watching me closely, “you feel about your Cal.”

Hard to get breath. Hard to speak. I was about to say it was the last thing I’d been thinking of when I realized it had been the only thing.

All along.

Even now.

“So you see,” Hart said, “you did not make everything up after all.”

Slowly she climbs the path to the inn, her wet gown chafing, sticking to her legs. He is waiting for her on the balcony: smooth faced, slim shouldered. He, too, has been crying. She sits beside him; he extends his hand. She takes it—what else can she do? At last they understand each other. Or perhaps she has understood him all along. He cannot love her, love anyone, completely.

This time, she is protected. Safe.

The first, cool fingers of breeze stir the air. The horizon goes gray, then pink. Clara feels something loosen around her heart, the first flaking pieces of a grief even older than Robert’s illness lifting away. Come September, she’ll be back on the road. She will travel to England, to Russia again. She will, she believes, see America this time.

She will, she believes, feel whole and well again.

When Hart turned out the electric candle, the whole world vanished in darkness. The sort of absolute darkness in which anything might be said. “You don’t love me,” I said. “You have tried, I know. But you can’t.”

“There are better things, more important things, than the kind of love you are meaning.” He turned in the bed to face me; his breath was strangely sweet. “Here is the truth, which I’ve tried to tell you ever since the second time we met. I don’t think I’ll ever love anyone the way I loved Lauren. I’m not sure now I would want to. One loses too much to a love like that.”

I thought of how Clara’s music suffered during the happiest years of her marriage. How Robert protected his art from Clara’s love behind the closed door of his studio,

behind the closed mind of his madness. The long years of sadness between Cal and me, during which time I published five books in six years.

Yes, Hart understood me. I understood him, too.

Art is about desire, is it not?

I’d chosen him, exactly, for this.

Date: Sunday, July 23 2:52 PM

Hi, Jeanie—

There’s this couple in their sixties and they’ve just gotten married and they decide that they want to have children. So they go to a fertility doctor, and he’s doubtful, but hey—cash is cash—so he hands them a container and says, Let’s get a sperm sample first. One hour later, the doctor comes back into the room, only to find the container is still empty.

“What seems to be the problem?” he says.

“Well,” the man says, “first I tried with my right hand, and then I tried with my left hand, and then my wife tried with both hands…but we just couldn’t get the cover off the container.”

In the end, I suppose, it all comes down to this.

Much love to you always, wherever life takes us.

L—

40.

B

REAKFAST AT THE INN

was coffee and bread, fruit and cold meat, cheese. Hart was already on his way to St. Gallen. I’d walked him down to the ferry dock, where we’d kissed each other good-bye. But I hadn’t wanted to spend the day flying with him, and he, in turn, hadn’t pressed. Something between us was already different. Some necessary tension had eased. At the end of the week, we’d meet in Zurich, in time for Friederike’s recital. Back in the States, we’d talk on the phone. I’d see him until he moved to New York. Perhaps, now and then, after that. And yet, as I’d walked back from the ferry dock, I felt as if I’d just been to a funeral. I saw him as if he were still beside me. I could hear his voice in my head. The room smelled, lightly, of his cologne. The shape of our bodies still hugged the bed.

After breakfast, I reserved the room for a second night, and then I wandered along the few waterfront shops until I found a bench overlooking a strip of rocky beach. My eyes blinked, burned against the fresh morning light. Déjà vu. At last I understood what the feeling meant, what it was I had recognized. It hadn’t been Hart after all. It had

been what he’d made me feel. Alive to the world around me. Alive, once again, to myself.

My cell phone buzzed. Heidi, at last. I cleared my throat, answered. But no—it was just Cal.

“I didn’t want you to worry,” he said. “She just doesn’t want to call you this time. I’ll try to put her on, though, if you like.”

“No, it’s okay. Is she happy?”

“Very happy. Settled.”

“If she’s happy, I’m happy.”

“You don’t sound happy. You sound kind of awful.”

How I wanted, at that moment, to tell him everything, to let him comfort me, console me, the way he’d done countless times during our married life together. All that I’d lost truly hit me then. I was alone in the world, I was truly alone. And yet, I must raise Heidi. I must go to work and come home. I must shop and cook and clean the house, balance the checkbook, take the car in for oil changes, repair the gutters, pay taxes. A privileged life, a blessed life, in a world filled with hunger and terror and want. It was shameful to admit, even to myself, that it all seemed impossible somehow.

“I’ve picked up a summer cold,” I said.

“That’s too bad.”

“It’ll pass,” I said. “Thanks for calling.”

“Listen,” Cal said. “I just wanted to say I’m sorry. For the way I acted the last time I saw you. It isn’t even true, what I said.”

“What you said?” I was trying to remember.

“Of course my girlfriend reminds me of you, in some ways. I mean, you and I had so many good things between us. Good years. We still do, don’t you think? I mean, after we get through this part.”

“After we stop being mad at each other,” I said.

“I want to stop.”

“I want to stop, too.”

“God, you really sound terrible.”

“I better hang up, I’m losing my voice. Give Heidi a kiss for me?”

It seemed as if I’d never look forward to anything again. Upstairs at the inn, I pulled the sheets over the bed, closed the thin curtains against the heat that was already spreading over the walls, thickening the moist, still air. I wanted so much to lie down in that bed, close my eyes and bury myself, disappear for the day. Instead I sat down in front of my laptop and turned to the work at hand, to the writing that has always sustained me, kept me whole, even when everything else around me falls apart.

“My true old friend, the piano, must help me,” Clara wrote in 1854, shortly after Robert was institutionalized. “I always believed I knew what a splendid thing it is to be an artist, but only now, for the first time, do I really understand how all my pain…can be relieved only by divine music so that I often feel quite well again.”

*

Perhaps, in the end, it was this belief that formed the cornerstone of their friendship. Clara Schumann could not have been the pianist she was, nor Johannes Brahms the composer he would become, had they not shared the same need to remedy longing.

To medicate loneliness.

41.

B

RAHMS ON THE TRAIN

back to Hamburg, then. Still young, still slender, but already beginning to carry himself with the reserve of a much older man. Hurtling toward his next love affair, and the love affair after that, toward the series of women he will choose because each is impossible to attain. Running through the maze of his heart’s desire, one which will lead him, again and again, to the same plain-faced, plainspoken mother of seven children, fifteen years his senior, mirror of his genius. Home. He will dream of her worn face, the fullness of her body, the broad weight of her hands. He will long for her even as he hates himself precisely for that longing. He will refuse himself the consolation she offers, as well as the consolation of her children, burdened not so much by disappointment as the constant expectation that things will go wrong.

Women are fickle. Whores grow annoying. The young pretty girl who attracts him has nothing of interest to say.

Years later, upon learning she is dying, he’ll clutch at his heart and cry out to a friend, “Apart from Frau Schumann, I am not attached to anyone with my whole soul! And truly

that is terrible and one should neither think such a thing or say it! Is that not a lonely life…”

*

“Although he loved human intercourse and sought it,” Eugenie Schumann would recall, “he was always on the defensive when he was sought after. He liked to give, but resented demands or expectations. He selected his friends very carefully, and there were not many who passed muster. Once, during the last years of his life, he went so far as to say, in an outburst of moodiness, ‘I have no friends, and if anyone tells you he is my friend, don’t believe him!’ We were speechless. At last I said, ‘But, Herr Brahms, friends are the best gift in the world. Why should you resent them?’ He looked at me with wide-open eyes and did not reply. Brahms undoubtedly has suffered very much. He was very human, as human as one can be, and that is why he was also much loved.”

†