Good Sex Illustrated

GOOD SEX

ILLUSTRATED

SEMIOTEXT(E) FOREIGN AGENTS SERIES

The publication of this book was supported by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, New York.

“Ouvrage publié avec le concours du Ministère français chargé de la Culture—Centre nationale du livre.”

This Edition © 2007 Semiotext(e)

1974 by Les Éditions de Minuit, 7 rue Bernard-Palissy, 75006 Paris

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Semiotext(e)

2007 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 427, Los Angeles, CA 90057

www.semiotexte.com

Special thanks to Robert Dewhurst, Andrew Berardini, and Jared Elms.

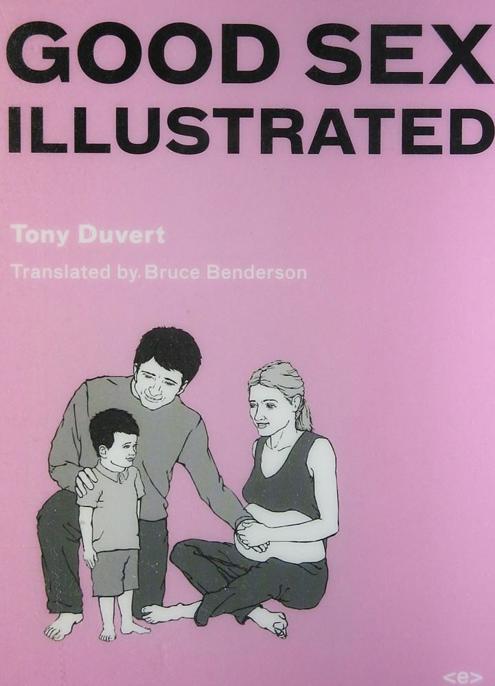

Cover art by Shannon Durbin

Design by Hedi El Kholti

ISBN-10: 1-58435-043-1

ISBN-13: 978-1-58435-043-9

Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. and London, England

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Introduction by Bruce Benderson

The Sexual Order and What It Serves

The Principle of Sex Education

This Is Where He Will Learn the Role of the Father…

To Live Happily, Live Castrated

The Sexual Market and Adolescence

Introduction

The Family on Trial

“

If there were a Nuremberg for crimes during peacetime, nine mothers out of ten would be summoned to appear.

”

—

Tony Duvert, interviewed in

Libération

, on April 10, 1979

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, the book you are about to read will change your life forever. Never before have you encountered a text as rigorous, as relentless, as energetically malcontent or as disgruntled. So step right up, if you dare. The subject? The Sexual Order of the entire Western World. Using structures and concepts that parallel those of capitalist economics, Mr. Duvert will demonstrate before your very eyes what our sex lives really are: exploited, objectified, imprisoned, profit-driven… and, above all, castrated. And when you limp away from the experience—now aware of how crotchless you are—you will forever after look with jaundiced eye at everything you once held dear: marriage, the couple, the protection of children, even psychotherapy.

Wait! Don’t put this book down. Tony Duvert’s rant against these oppressions, which he somehow manages to sustain from start to finish at a manic, nearly delirious level of analysis, subsistson a much more exciting turbulence than the sex activism to which we Americans are today accustomed, with its shallow bromides about the objectification of women, child abuse or the rights of gays to marry. From a position that is nearly converse to these concerns, Duvert points a rageful finger at the strangulation of

pleasure

by capitalist shackles. He demonstrates that, in our sexual order, orgasm follows the patterns of any other kind of capital: it is commandeered by the State, which ensures that its consumption will always be tied to another’s profit, and that any free, or pointless, expenditure of sexual energy will be forbidden.

A disaster from the start, given that sexual energy only brings pleasure when its expenditure

is

“pointless”: as play, as experiment or as an expression of good feelings. Today’s “good sex,” however, is a voracious profit machine. Its tactics begin when the sex of young children is “castrated” in the name of familial order; continue into pubescence, when sexual energy is diverted, or “commandeered,” with the help of contemporary sex education so that any sex outside the family will be thought of as “perversion” or molestation; and, finally, climax at adolescence, where the deformation of the sexual instinct gets its finishing touches by the artful mechanism of guilt, until sex finally becomes an investment toward future profit for the State.

And what is the investment into which our poor, abused capacity for orgasms will inevitably be put?

Baby-making.

That the cycle continue!

Who is Tony Duvert, and has he always been concerned with these issues? He has. But

Good Sex Illustrated

marks a dramatic turning point in his literary production. A novelist firmly rooted in the

nouveau roman

, he won the prestigious Prix Medici for his 1973 novel,

Paysage de fantaisie

, a year before the publication ofthis essay. The novels that followed after

Good Sex Illustrated

were no longer experimental in narrative style, going so far as to adopt a conventional realist (or “pseudo-realist,” as he told an interviewer) narrative approach. It’s as if the experience of writing nonfiction had showed him the importance of expressing his ideas as clearly as possible, and he looked back on his experimental past as a dialogue with himself. From then on, his writings would be turned outward, more overtly political and much more accessible.

Essentially, Duvert’s analysis of the sexual order is in contradiction to most of today’s sex and gender “liberations,” all of which are careful to respect motherhood and the crucial social importance of nuclear family values. But it is the nuclear family itself that, after being exploited, exploits in turn, first through motherhood, and later through the authority of the father: it commandeers, castrates and twists the child’s sex instinct into a sullen instrument of power in the name of protection and education. It isolates him from the outside world and portrays it as fraught with danger. This is, Duvert makes clear, the same system that has manufactured the idea of the stranger as the molester of children, just to keep the child from any outside influence or contact with a non-family adult who might have a chance of removing the veil of family enchantment. Such an invention (and Duvert insists that it is an

invention

by pointing out the statistical infrequency of violent molesters who are strangers and comparing the risk for harm from such people to the much greater one of riding in the family car) serves to deflect attention from the real psychological molester of children: the father.

Father

as

castrator

and perpetuator of the exploitive capitalist system;

mother

as passive

baby-machine

that fashions

child marionettes

;

child

as

victim

of both, his sex crushed in the name oforder, his chances for free expenditure of sexual energy prohibited: this is the grim picture that Duvert presents, using as data a liberal, cheerful French manual of sex intended for children and adolescents and published in the early 70s, a year before

Good Sex Illustrated

was written. Duvert analyzes this text with an obsession bordering on rapture and builds a narrative of nearly total sexual devastation. And because he uses this liberal sex manual for his case study, his text becomes a massive project in the construction of irony, at the very moment in Western culture when sexual liberation was supposedly blossoming.

This, in fact, is the great value of

Good Sex Illustrated:

its Cassandra-like shrieks of doom in the midst of a celebration of sexual victory at the dawn of our contemporary sexual mores, its spitting in the face of the good doctors, therapists and teachers at the moment they are tipping their hats to the “love generation” and congratulating themselves on their alacrity at guiding children through the twisted maze of sexual development. These good educators will be revealed by Duvert as so many spineless collaborators; so the question is, I suppose, whether, some thirty years later, Duvert’s poisonous analysis can now be interpreted as an accurate, ominous prediction of life today, or whether his complaints have been proven to be somewhat off mark.

Both, in my opinion. Much more than, say, Orwell’s

1984, Good Sex Illustrated

has turned out to be uncannily predictive. And just as Duvert implied, very few of us pawns in the game are aware of it. Take for example, his analysis of the bourgeois homosexual, who hopes by collaborating with family values to build a niche for himself in the exploitive sexual order, thereby positioning himself for a little pleasure. Such behavior has reached “epidemic” proportions today. Or the increase in the manufacturingof the evil stranger-sex-offender as repository of all our anxieties about sex, as a mask for our covert exploitation of others and to control, rather than protect, the sexuality of our children. Or our use of the family-values alibi in general to consolidate more and more privileges in the hands of a certain segment of the middle class.

On the other hand—and this is depressing—the part of Duvert’s argument that seems off mark is that small aspect of it that is optimistic. He hoped that measures placing sexual choice in the hands of minors in countries such as Denmark, where the age of consent had just been lowered to 14, would eventually produce a generation—the next one—that would be free of those constraints that perpetuate the abuses of the sexual order.

Todays young adults are that very generation, and they certainly exhibit a greater nonchalance about sex than generations of the past; but are they any freer? They are, rather, a generation of disillusioned libidinists, who see little value in “unleashing” the energy of the orgasm and blame their permissive parents for dissipating the power of sex and endangering it with new diseases. Finally, there are certain phenomena that Duvert interpreted as symptoms of the oppression of the sexual order, such as a lack of concern about the physical abuse of very young children within the home by parents; but now that public attention has focused on these problems, it hasn’t brought us any closer to liberation from the sexual order he described.

Even so,

Good Sex Illustrated

should be lauded as one of the more brilliant deconstructions of systems of capitalist exploitation. In that capacity, its relevance will live on for many decades to come. Once we have learned to look at sex as an economy, it becomes overwhelmingly clear to whose profit that economy functions. That is also the moment when many aspects of our ownlives that we thought of as the results of choices are suddenly reinterpreted as programmed stimulus-response patterns drilled into us by punishment, lies and the withholding of rewards.

That said, I think that some brief remarks about the translation of this work are warranted. In several key instances, a word that had two essential meanings in French—one to do with economics and the other to do with behavior—could not unfortunately be employed with the same double connotation in English. For example, the French word

détournement

can signify the misuse of public money, but it can also refer to the corruption of a minor. I was not happy with some previous English translations of the word as “detournment” when referring to the

détournement

of the Situationists, so I had to be content with the translation “misappropriation,” which is inadequate, but its full meaning progressively becomes clear in the contexts in which Duvert uses the word. Even a French word as seemingly straightforward as

aliener

, often used by Duvert to describe the effect of sex education on the young person’s sexuality, also had economic connotations in this text because

aliéner un bien

means “to dispose of property.” Additionally,

consommation

in French can mean either “consumption” (an economic term) or “consummation” (relating to sex and marriage), so I had to resort to the use of both words in English, creating an association between the two as best I could. There are a dozen other examples, and even the usually difficult

jouissance

(does it mean “pleasure,” “orgasm,” “thrill,” “enjoyment” or something more?) entailed extra problems because of the fact that

avoir la jouissance

refers to the full use of a property under the eyes of the law.