Good Mourning

Authors: Elizabeth Meyer

Thank you for downloading this Gallery Books eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Gallery Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

To Dad, Mom, and Damon

Happiness is beneficial for the body,

but it is grief that develops the powers of the mind.

âMARCEL PROUST

Prologue

W

e're all going to die.

I'm not trying to bum you out. And I also know that somewhere, deep down, you are perfectly aware of the fact that none of us will be here forever. Death is a tough topicâit's scary to think about dying, and it's not any

less

scary to think about losing someone you love. So we have a tendency to not talk about “the end” and all the things that come with it: funerals, gravestones, the nail-biting decision of whether to adorn your loved one's casket with orchids or peonies.

But not you, who picked up this book and thought,

Give me some of that sweet funeral knowledge!

You're not afraid. You're open-minded. And I dig that about you.

Not everyone is so relaxed when it comes to death, though. In fact, sometimes the people who have it all in this

life are the ones who are most afraid of it. I guess when Âeverything around you is so gosh-darn fabulous, you don't want the curtains to close. I get that. But even the people in the high-society circle I've been running in since I was born can't escape the same fate as . . . well . . . every living thing ever. (I know, I know . . .

Did she really just say “high society”?

But there's just no term for the people I grew up around that doesn't solicit an eye roll. Trust me. I've Googled.) I guess what I'm trying to say is, death is hard for a lot of us to accept . . . and perhaps especially difficult for people who are accustomed to getting what they want, when they want it. “Yes, your car is waiting for you.” “Yes, we'll find you a table.” “Yes, we can custom-make that for you.” “No” is simply not part of their vocabulary. “No, there is not a cure.” “No, there isn't anything else we can do.” “No, it won't make a difference if you pay me in Louis Vuitton suitcases filled with cash.”

Don't get me wrong, the purpose of this book isn't to make fun of a bunch of silly rich people; in fact, I changed names and identifying details. If anything, death is the one experience other than birth that unifies all of usâfrom the guy who drives the limo to the CEO of the company who built its engine. And since we can't avoid it, well, I figure we might as well embrace what we've got coming. That's part of the reason I got into the death business in the first place. When I was twenty-one and most of my friends were

Daddy-do-you-know-someone?

-ing their way into fancy banks and

PR firms, I was grieving the loss of my father, who had just died of cancer. That's how I found myself in the lobby of Crawford Funeral Home, one of several premier funeral homes in Manhattan, begging for a job one day. This might not be politically correct, but I'm just going to say it: anyone who's anyone in New York Cityâor rather, anyone who's anyone who's

dead

in New York Cityâwinds up at Crawford. It's where loved ones said good-bye to everyone from John Lennon and Jackie O to Heath Ledger and Philip Seymour Hoffman. If you can afford it, it's just

where you go

.

One last social gathering to finish off a lifetime of champagne toasts.

Of course, not everyone in my life thought that my sudden desire to hang around dead people was as amazing as I did. Seriously, you would have thought I'd traded in all my Armani gowns for some goth-chick combat boots and black lipstick. My best friend, Gaby, thought I was having a quarter-Âlife crisis. My mom, well, she had to practically hold herself up against her Nancy Corzine sofa when I told her the news. “But, Elizabeth,” she said, her perfectly manicured nails digging into the velvet. “You could work in

fashion

.” Even my brother, Max, who usually doesn't give a damn what I do as long as it doesn't embarrass him (for which I should probably apologize now), was concerned. “Does this have to do with Dad?” he asked late one night when he called from his prestigious white-shoe law firm. “Mom's worried.”

Maybe it

was

a little weird for a woman in her early twenties to choose to work at a funeral homeâand I'm sure my dad's death had

something

to do with it. But mainly, I think I liked being there for people when they needed it the most. I've said it a million times: just because you pull up to a funeral in a Bentley wearing Dior doesn't mean that it hurts any less. Death is death. Grief is grief. And as it turns out, I have a gift for planning last hurrahs for the richest of the rich (and sometimes the craziest of the crazy) so that their families can feel comfort during a really difficult time. When clients walked into the foyer of Crawford, with its ginormous ceilings and eight-foot oil paintings, I would greet them and they'd instantly relax. As one old lady in pearls once told me: “I can tell you're one of

us

.”

But things didn't always run so smoothly. There was the time I lost a body, the time I had to deal with a dead man's two wives (not ex-wives,

wives

), the time I urgently raced around Crawford looking for a fucking brain. In my years there, well, I saw it all. And like any good funeral planner, I've kept those stories locked up tight.

Until now.

ONE

It Starts with an Ending

Y

ou know that feeling when someone tells you bad news, and for a second, it's like you're watching someone else's life happen to

your

life? And then, after you've had a moment to absorb it all, there's this moment of panic. You realize you can't fast-forward to the happy scene where all the characters break out in a dance or clink their glasses of wine together over a table because

Whew, thank God

that's

over

.

Now somebody roll the freaking credits.

That's how I felt when my dad, whom the rest of the world knew as Brett Meyer, told me he had cancer. If my life had a soundtrack, the music would have stopped in that moment.

My

dad? Cancer? Impossible.

That's not my movieâat least, I was naïve enough to think it wasn't when I was sixteen. Up until then, my life had been about ski vacations to Vail, weekend trips to Palm

Beach, and partying with my best friend, Gaby. Know where we had our Sweet Sixteen? At a club in New York's hip Meatpacking District. It was total excess: bamboo invitations to three hundred friends, Mark Ronson at the turnÂtables, a gaggle of models circling around the dance floor. Gaby and I spent half the night sneaking Long Island Iced Teas and cosmopolitans into the bathroom (those seemed cool to drink at the time) and the other half grinding up against prep-school boys trying to move their Ferragamo loafers to a beat. At that point, the biggest problem in my life was whether we should go with buttercream or fondant for our five-tier birthday cake.

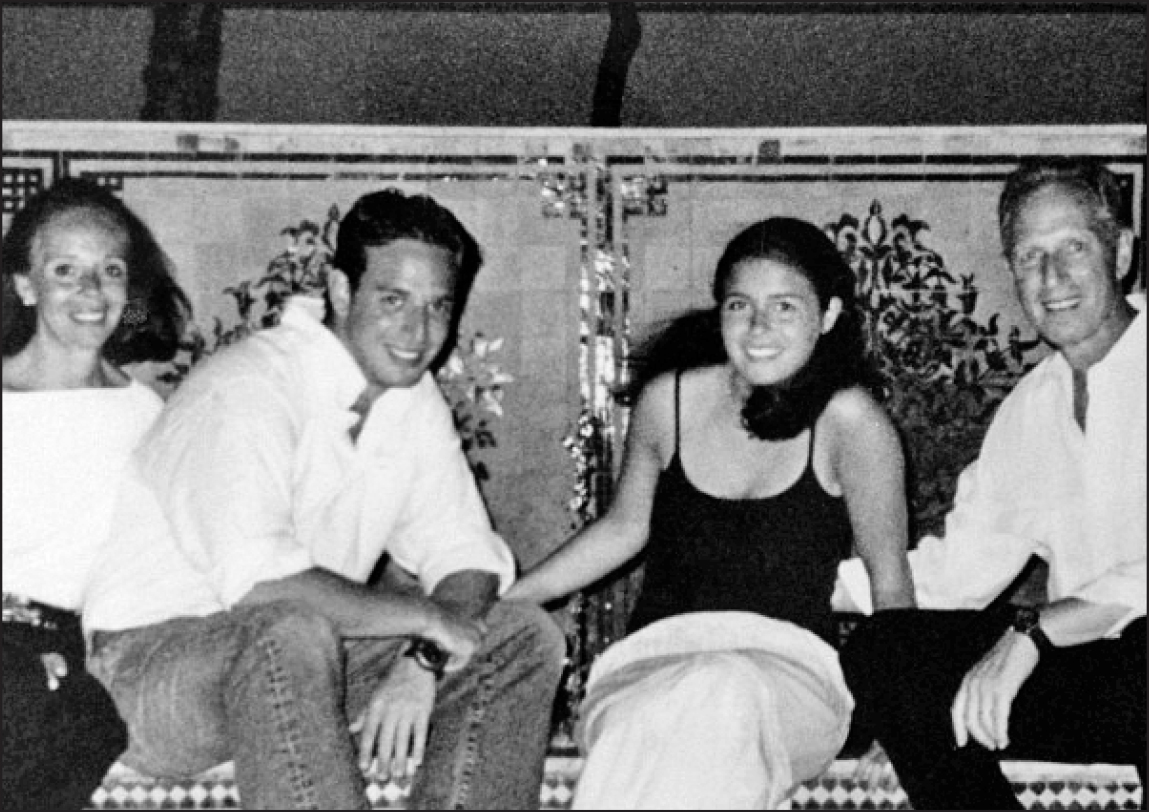

To his credit, my dad didn't want to make a big deal about the whole cancer thing, and so after the initial shock of his diagnosis, my mom, Francesca; my brother, Max; and I went back to business as usual. Dad occasionally scooted to the hospital for a quick chemo treatment, but we treated it more like he was going to a hair appointmentâa weekly “touch-up” to make sure no roots were peeking through. He never acted like he was going to die, or like death was even a possibility, and so we didn't think that way, either. Even nine years later, my mom can hardly believe that he's gone. “I never once thought this would happen,” she says. Mom has always been a realist but still thought, as most of us do, that the bad stuffâthe cancer, the car accident, the overdoseâhappened to other people. Not her. Not her family. Not my dad.

Part of what made Dad seem so untouchable was his personalityâyou just couldn't shake him. One of my favorite stories is from early in my parents' marriage when they took a trip to Key Biscayne, Florida. Dad got this idea to rent a catamaran, even though my mom thought they should play it safe on the beach. (This was a common theme in their marriage: Dad was the adventurer, Mom was the voice of reason . . . or at least practicality.) “Something

always

goes wrong,” she said to him. But Dad was all, “No, no, it'll be great!” andâthanks to his lawyer skills and a smile that always got herâthey went. A couple of hours later, there they were on the catamaran, watching the sunset, when the thing

split in half

. Mom wasn't a great swimmer, so she hung on to a piece of the broken boat, bobbing up and down in the water, as the sky grew darker and darker. “Are there sharks?” she asked my dad, terrified. He looked around, treading water. “Probably,” he said, as if he were talking about guppies. A couple of hours laterâyes,

hours

âa boat finally noticed them and came to the rescue. Know what Dad wanted to do the next day? Go sailing.

Mom settled into the Upper East Side well, but she grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Queensâthe type of place where big Italian families got together after church every week for macaroni and Sunday sauce. While Dad studied at an expensive private university in New England, she was keeping it real living at home while going to college in the city. In fact, they probably wouldn't have metâLord

knows their social circles never overlappedâif my mom hadn't randomly befriended an acquaintance of my father's while she was on vacation. By the time her plane landed back in New York, she already had a missed call from my dad. She only called him back because

her

mom insisted it was rude not to at least respond, and she eventually agreed to go out with him for the sole reason that he asked her out for a Tuesday. Mom had other options, and she was not keen on giving up a Saturday night for some what's-his-face on the other side of the river.

Dad, on the other hand, grew up in a mansion in Scarsdaleâan affluent New York suburb where extravagant homes line the streets and people have pool houses and gardeners. His mom, Elaine, was less than welcoming when Dad brought home a girl from Queens. My mom still talks about the horror of their first dinner: Elaine kept kicking under the table, shouting, “It's not working! It's not working!” Only later did Mom realize that the “it” was a bell attached to a wire used to signal the help, either to clear a plate or fetch her something from the kitchen because

God forbid she get up

. Dad, who had cut the wire, laughed off his crazy mother's behaviorâsomething he was always able to do. (Me? Not as much. Elaineâyes, I called my grandmother by her first nameâwas the epitome of a society snob.) Even at stuffy charity dinners and black-tie parties, Dad was always able to keep a sense of humor about the whole thingâthe money, the people, the

scene

. He used to

say, “Never own something you can't afford to lose, Lizzie.” I never forgot it.

So when it became clear that, after he'd been fighting cancer for five years, I might actually lose my dadâthe one thing I couldn't imagine living withoutâI struggled to wrap my head around it. I started to treat Dad's hospital stay like he was shacking up at a nearby hotel. After a night clubbing with friends from New York University (where I went to college so that I could stay close to my father), I'd head to a bagel shop at five a.m., pick up a half dozen soft, doughy pieces of heaven and a tub of cream cheese to share with the nurses, and head to Dad's hospital room for breakfast. He never said a word about my probably too-short skirts or probably too-high heels. We'd just talk about how the Giants played last weekend and if they had a shot in hell on Sunday.

Then one morning before a major surgeryâone that he might not make it out of, the doctors told usâmy father finally admitted that there was a chance, a slight chance, that he wasn't going to be there to do all the things we'd planned. There might not be another trip up to our country house in the Berkshires, where Dad used to pull my friends and me on an inflatable tube around a frozen lake from the back of a four-wheeler. There might not be another family trip to Europe, or sail up the Hudson, or even early-morning bagel breakfast; no more father-daughter dates to the Met Ball or summertime canoe races. There might not be more of our Âfavorite things, because time might be up.

And then, just like that, it was.

I remember getting the call: I was out walking our black Lab, Maggie, and didn't have my phone on me, but I just got this feeling in the pit of my stomachâsomething told me to get home, and fast. When I ran through the door, I grabbed my cell phone without so much as taking off my coat and saw that I had ten missed calls from Max and my mom. I didn't check the messages. I didn't have to. I knew what this meant. The only person I did reach out to was Elaine. I knew she was on her way to the airport, eager to get back to her bridge games and Russian wolfhounds, affectionately and ridiculously named Smirnoff One and Smirnoff Two. (For all her fantastic taste in designer clothes and vintage cars, Elaine had terrible taste in booze.) I figured she'd want to have the car swing back around ASAP to the hospitalâthis was her son, after all. But instead she just sighed into the phone. “Lovey girl, I

have

to get back.” Elaine had never been maternalâI'd never once seen her even hug my dad, and the only way she ever showed me affection (if you can call it that) was by tapping on her nose and demanding a kiss.

On her nose.

Although, what can you expect from a woman who hid a bell under the table to summon her staff?

When I returned to the hospital, Dad was lying in his bed, with Max standing behind him and my mom at his side. My uncleâDad's brotherâwas also there with his wife. The doctors explained what was about to happen: Dad needed to be put into an induced coma so that they could try to elevate

his white blood cell count. First, they would need to stick a tube down this throat. After that, he would be on a ventilator and would soon be completely unresponsive. They were clear that the odds were stacked against us, and there was a good chance Dad might not wake upâever. But they were also clear that there was no other option except to take no chancesâvery unlike Dadâand lose him anyway within days, even hours.

I walked around to the other side of the bed, opposite from where my mom was standing, and held my dad's other hand. He looked up at me calmly, even though he knew exactly what was going on. “I love you,” I said, somehow managing to stick to the group's code of not crying, not even now. “It'll be fine,” Dad replied.

I stroked his hand while a nurse pushed the breathing tube down his throat and then as they wheeled him away. For the next two days, Max and I swapped turns sitting by Dad's side in the ICU. Max read him short stories by Kurt Vonnegut, and I talked to him about nothing in particularâalthough I did ask him,

beg him

, a few times not to leave me. “What would I do without you?” I asked, sometimes jokingly, other times desperately. I wondered if it was true what they say about people in comas being able to hear and feel you. Staring at my father lying there, hooked up to a gazillion machines, it was hard to imagine that was possible. In a lot of ways, I wished that he had already gone somewhere else. If he'd been able to speak, I'm sure he would have said

something like, “This place sucks. I mean, talk about a bunch of stiffs. Let's get out of here.”

Finally the doctors told us what we already knewâDad wasn't coming out of it. So we once again gathered around his bed, my mom and I each taking one of his hands, and prepared ourselves for another good-bye . . . this time, the final one. The machine with Dad's vitals went from

beep-beep-beep

to

beep . . . beep . . .

to one long, steady beep, just the way you think it does. And while my heart was aching, the scene itself lacked much drama.

Before we headed out to the garage to get the car, I grabbed Dad's cell phoneâwhich was still ringing with calls from clients and friends, many of whom he had never even told he was sick. Up until his death, Dad had still been holding meetings in his hospital room, where a bunch of associates from his office (they of course knew he was sick, but not

that

sick) would stand around and debrief him on this case or that case, while Dad told them how to handle things. He had never let on that he might not make itâand so there it was, a cell phone filled with missed calls and voice mails, going off once again.

“Hello, this is Elizabeth speaking,” I answered, trying to keep my voice steady even though my mind was spinning.

Is this really happening?

I thought.

Am I really answering Dad's phone, because Dad is gone?

“Hi there, Elizabeth. Can you put Brett on? We have a question and I think heâ”

“I'm so sorry, but my father isn't available.”

“Oh. Okay. Well, just tell him thaâ”

“He passed away,” I said, blurting the words out, getting them over with.

“What?”

I took a deep breath, willing myself to say it again. The room spun faster. “He passed away. It just happened.”

Silence.

More silence.

“Oh my God.”

“We'll be in touch with the firm as soon as we've made arrangements,” I said, a weird numbness setting in.

There was another missed callâseveral, actuallyâfrom Elaine. She'd been dialing me, Max, and Mom, one after the other, for the past few hours, and we'd all been hitting “ignore.” I listened to her voice mail, which said, and I kid you not: “Lovey girl. It's Nanny calling. I've started running a bath. I'd like to know how your father is before I get in. And you know nobody likes to soak in cold water. Call me.”

I felt a wave of rage come over me. She knew damn well when she strapped her tweed-covered ass into her first-class seat on the plane that she was never going to see her son again.

How is he doing?? Are you fucking kidding me??

I picked up the phone, dialed her number, and barely let her voice ring in my ear before opening my mouth:

“He's dead,” I said. Then I hung up.

When I got back to my parents' Fifth Avenue apartment,

it occurred to me that everything should be differentâand yet everything was the same. Maggie wiggled to greet us at the door, unaware of what we'd all just lost. A copy of the

New York Times

from that morning remained on the entrance table, unread. The silver picture frames on the living room mantel tilted just soâeach filled with images of my father and my whole family in happier times, staring back at me as if to ask,

Why so sad, Lizzie?

I grabbed my phone, wrapped myself in a yellow cashmere blanket, and slumped onto the edge of the couch. Then I looked up the number for Crawford Funeral Home, just a couple of blocks away, to schedule an appointment. It might sound weird that at twenty-one, I was the one who took on the responsibility of arranging my father's funeral. But to be honest, I didn't trust anyone else to get it right. Besides, unlike my mom and brother, who were being comforted by adoring friends and family in the next room and noshing on some of the pounds and

pounds

of catered food our family had ordered (Italians grieve with carbs), I preferred to be alone. A few minutes later, I had an appointment scheduled with the funeral director for the next morning.