Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck (20 page)

Read Good Manners for Nice People Who Sometimes Say F*ck Online

Authors: Amy Alkon

Driving Miss Crazy: How and why to rein in your vengeful impulses.

If “blue language” actually came out that color, the ugly things I’ve snarled from inside my closed car at rude drivers and willfully sluggish pedestrians would long ago have transformed the interior from Honda gray to a singed hellfire blue. But I’ve managed to stop throwing these in-car tantrums. Understanding moralistic aggression helps me understand why I get so enraged and why my rage at some rude passing stranger no longer does the job it would have on some similarly ill-mannered member of the hunter-gatherer band way back when. Understanding biochemistry reminds me of the negative health effects of flying into a rage—sending my blood pressure skyrocketing, poisoning myself with surging stress biochemicals like cortisol, and sometimes giving myself the jitters and a sour stomach for hours afterward.

This isn’t to say I now—

poof!

—magically transform into Becky Buddha when some driver, upon spotting my car trying to enter into traffic, hoggishly darts forward, stopping squarely over big white words on the pavement,

KEEP INTERSECTION CLEAR FOR CROSS TRAFFIC

. Not vaulting into a rage takes preplanning—reminding myself in unheated moments about the pointlessness of getting all bent up. For example, unless you have a rocket launcher on top of your car—and precise aim, to boot—the driver who’s just taken a big crap on your existence will likely just keep tooling along with little or no idea of the bug-eyed, mouth-foaming lather you’ve worked yourself into. And how completely unsatisfying is that?

But let’s say some rudeness-inflicting driver is more accessible, maybe getting out of their vehicle in a parking lot or driving alongside you in an adjacent lane. It becomes enormously tempting to fly out of your car and send your tire jack on tour in a place with less sun than Iceland or at least roll down your window and speculate loudly on their mother’s sex practices. In such moments, ask yourself whether you want to give some person with all the gentility of a cockroach a say in shaping who you are—which is created through the sum total of how you behave. If not, the answer is not just swallowing whatever they did to you but channeling the adrenaline wave pushing you to do something awful to them in response and instead doing something extremely nice for some nearby stranger. You’ll still get some physical and psychological release from taking action—the warm fuzzy that comes from surprising a stranger with an act of kindness or generosity plus the satisfaction that you didn’t let some lowlife turn you into their rage-bot.

Finally, it can help to recognize that whether you excuse a driver’s behavior as a result of simply being confused or preoccupied (rather than flagrantly rude) often depends on whether you happen to be that driver. This is called “attribution bias” and describes how we tend to think far more charitably about ourselves and our own behavior than other people and theirs. It’s something to remember the next time the light turns green and the driver in front of you is just sitting there growing roots—just like he did at the previous light. Consider the possibility that he is lost and looking down at his directions—tempted as you are to believe that he knows who you are, sat outside your house waiting for you to leave, and then followed you down the road just to screw with you.

IMPOLITE AT ANY SPEED

The following sections cover the specific dos, don’ts, and how-to-get-them-to-stop-doing-thats in a variety of transportation arenas: sidewalks, moving sidewalks, elevators, escalators, public transportation, streets, parking lots, street parking, police traffic stops, and airplanes. Subjects grudgingly excluded are sleepwalking, driverless cars, jetpacking, and teleportation. But, about that last category, just a reminder that it’s always nicer to say “Beam me up,

please

, Scotty,” providing you aren’t about to be eaten by something with one big purple eye.

HAVE YOU BEEN RUN OVER BY A FORD LATELY?

Stopping the spread of cur culture in driving, parking, and traffic cop stops.

One car, one parking space. Even if your car is a Ferrari.

My ‘hood-adjacent Venice, California, neighborhood became “hot” a few years ago, which is great for people who like to be in walking distance of both a $10 cup of coffee and a $10 hit of heroin, but it’s become really hard to find parking.

One day, my boyfriend drove over with cheeseburgers he’d picked up for us to eat before we went out. For twenty-some minutes, he drove round and round looking for a space, but there was not one to be had anywhere remotely nearby. Knowing I wasn’t ready to leave, he phoned me from his car, telling me to come outside for a moment. He put his flashers on, handed me my burger, and drove a half-mile to the big office supply store on the boulevard to eat his in the parking lot.

The memory of our drive-by lunch makes it especially maddening when somebody with fancy-ass wheels parks on my block like the Porschehole taking up two spaces in Irvine (in the photo at the start of this chapter). Parking like this is not just hoggy but idiotic. Although the person’s Bentley or whatever

could

get a boo-boo on its bumper while taking up only one space, taking two is like taping a note—“KEY ME!”—on the hood of the car. And no, I’m not suggesting that’s okay to do.

My friend Doug knows how to park a really nice car. He had driven over to my house so we could walk to a bar in my neighborhood and grab a drink. When I came out of my gate with him, it was like my little Venice shack had gotten caught in a tornado and landed in Bel-Air. Sunning itself directly in front of my house, between my neighbors’ little beatermobiles, I saw this gleaming black ocean liner of a Mercedes—Doug’s new car.

Uh-oh. It would surely get scraped by somebody parking or pulling out, and he would hate me a little every time he saw that scratch. “Um, this street is probably not a good place for you to park,” I said.

Doug laughed. “It’s just a car.”

Right on.

Absolutely right on.

And if

that’s

not how you think of

your

ritzywheels, whenever you’re contemplating driving to an area where the parking is scarce, you really should think again—and then build your car a velvet-lined, temperature-controlled garage and leave it there to be dusted on the hour by its nanny.

The self-crowned queen of the parking lot and the beauty of positive shaming

If you are a frail 9,000-year-old lady or you just had your knee replaced with four steel pins and sixteen thumbtacks and you lack a handicapped placard for your car, you get a pass for waiting for a primo parking space near the door of the drugstore. Otherwise, you don’t get to back up traffic behind you while you wait—and wait and wait—for some other car to pull out, you lazy cow.

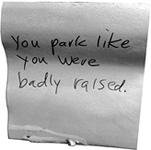

When people do this and, once in the store, don’t look the type to cause me disfiguring injuries, I’ll call them out on their rudeness if I can catch their ear. I do this both to make them pay for being rude with a hassling conversation and because I’m a big fan of shaming as an inhibitor of future rude behavior. Otherwise, I like to leave a shaming note on their windshield, and I keep a pad of Post-it notes and a pen in my glove compartment for this purpose. Here’s one of the notes I left on a car in my neighborhood—parked dead-center in a two-space spot between a driveway and a red zone:

The shaming note is at its most powerful in a residential neighborhood, where the rudely-parked car is likely to belong to a rude resident. If that person has any conscience or concern for their reputation, they have to wonder whether their neighbors strolling or walking the dog saw the note on their windshield about what an inconsiderado they are.

For those worried that they’ll be struck with writer’s block when it comes time to shame the parking piggy, there are packs of temporarily sticky bumper stickers like “I park like an idiot” for sale on the Internet.

34

The beauty of these or the shaming note tucked below the lip of a car trunk is that the offender may unwittingly drive around with it for quite some time, announcing to the world exactly the sort of ill-raised jerkus they are.

Neighborhood parking culture and when shaming notes go too far

Shaming notes should go after people for their rotten behavior alone. Those that go further—attacking a person’s looks or size—usually end up being ruder than any rudeness or perceived rudeness they’re responding to, as evidenced by a cruel note left on the car of an Oregon woman’s sister. The sister had driven over to stay with the woman for the weekend and had parked in front of the house across the street simply because she’d come from that direction. (That’s the sister’s car in front of the neighbors’ house below.)

The woman explained in an e-mail to me that her sister’s car was “the only car parked on the street for three whole blocks, and there was easily room for another five cars in these people’s driveway. Plus there’s the little detail that she was parked legally on a public street.” Yet the neighbors saw fit to tuck a hateful rant under the sister’s windshield wiper blade, addressed to “the idiot owner of the green Pontiac.”

“I realize that you’re probably too busy stuffing your face to care,” wrote one of them, going on to inform the sister than they have a busy household and lots of cars coming and going, including those of clients. The neighbor told the sister to move her “P.O.S. car” further down the street or across the street where she would be “all weekend long,” or they’d “block her every time.” The neighbor couldn’t pass up a final opportunity to go mean: “I figured that a fatty like you would want to park as close as possible to your destination anyway!”

The woman told me that her sister was “completely mortified,” which clearly was the neighbors’ aim, as anybody with an IQ topping the speed limit in a school zone doesn’t expect to say to somebody “You stupid, ugly piece of shit!” and then have them respond, “Oh, sorry! I’ll do my best to change!”

In fact, if I were the sister, I’d be tempted to park squarely in the middle of these cruel creeps’ front lawn, if not in their living room. And if I were the woman living across from the cruel neighbors, I would have sent a note back, stapled to a copy of the original (so the neighbors would have to revisit their ugliness), but swap an expression of sympathy for the neighbors’ low blows. Something along these lines:

You could have written a polite note requesting that my sister park on my side of the street, though on a public street you have no right to dictate where anyone parks. Still, a respectful request would likely have been honored. I’m going to assume there’s something terribly wrong in your life or marriage for you to feel the need to lash out at another person as you did. This allows me to feel sorry for you instead of angry with you. I hope things get better for you.

By taking action—sending a note rather than just casting hurt looks in the direction of the neighbors’ living room—the woman is refusing to act like a victim. Keeping the note free of low blows says that the neighbors don’t get to pull her strings, directing how she acts or the kind of person she is. And showing sympathy rather than anger, though still a reaction and maybe not an entirely believable one, removes much of the satisfaction the neighbors would surely get from a response in kind and sucks a good deal of air out of any feud the neighbors may have been hoping to incite.

Now, there is such a thing as parking culture in a neighborhood—unwritten but often widely accepted rules about how people should park. Weirdly, the rules are usually the most rigid in neighborhoods where the parking is most ample and typically involve the dictate that residents and their visitors must always park in the resident’s driveway—or at least in front of their house.

Even if you think it’s ludicrous that there are rules about parking on a public street, it might make sense to respect them. Consider the trade-off: whether it might be worth it in exchange for keeping civil relations with persnickety neighbors. The nastier your neighbors are the more it might pay to go along with their odd minor demand. (More about this in “The Neighborhood” chapter.)