Going Solo (22 page)

Authors: Roald Dahl

I had a window-seat and David was beside me. Only twenty minutes ago we had been in among the smoking olive trees and the burnt-out tents. Now we were 1,000 feet up over the Mediterranean and flying towards the North African coast. The sun was going down and the sea below us was turning from pale green to dark blue.

‘We’ll have to do a night landing,’ I said.

‘That will be nothing for this pilot,’ David said. ‘If he could take off from a piddling little field like that with all of us on board, he can do anything.’

We landed two hours later on a moonlit patch of sand known as Martin Bagush in the Western Desert of Libya. In the dark we found a truck which was going back to Alexandria through the night and all of us pilots got into it. We arrived in Alexandria early the next morning filthy, unshaven and with nothing to carry

except our Log Books. We had no Egyptian money. I led the lot of them, nine young pilots in all, through the streets of Alexandria to the marvellous mansion that was owned by Major Bobby Peel and his wife. They were the wealthy English couple who had put me up during my convalescence a few weeks before. I rang the doorbell. The Sudanese butler answered it. He stared in alarm at the bedraggled group of young men standing on the doorstep.

‘Hello Saleh,’ I said. ‘Are Major and Mrs Peel in?’

He went on staring. ‘Oh sir!’ he cried. ‘It’s you! Yes sir, Major and Mrs Peel are having breakfast.’

I walked into the house and called out to my friends in the dining-room. The Peels were wonderful. The whole house was put at our disposal. There were bathrooms on all four floors and we swarmed into them. Razors and shaving soap and towels appeared from nowhere. All of us bathed and shaved and then sat down around the huge dining-table to a sumptuous breakfast and told the Peels about Greece.

‘I don’t think anyone else is going to get out,’ Bobby Peel said. He was a middle-aged man too old for service, but he had a high-powered job somewhere in military headquarters. ‘The navy is trying to rescue as many of our troops as they can,’ he said, ‘but they are having a bad time of it. They have no air cover at all.’

‘You can say that again,’ David Coke said.

‘The whole thing was a cock-up,’ someone said.

‘I think it was,’ Bobby Peel said. ‘We should never have gone into Greece at all.’

Alexandria

15 May 1941Dear Mama,

Well, I don’t know what news I can give you. We really had the hell of a time in Greece. It wasn’t much fun taking on half the German Airforce with literally a handfull of fighters. My machine was shot up quite a bit but I always managed to get back. The difficulty was to choose a time to land when the German fighters weren’t ground straffing our aerodrome. Later on we hopped from place to place trying to cover the evacuation – hiding our planes in olive groves and covering them with olive branches in a fairly fruitless endeavour to prevent them being spotted by one or other of the swarms of aircraft overhead. Anyway I don’t think anything as bad as that will happen again …

The Grecian episode was a very small part of the war that was raging all over the world, but so far as the Middle East was concerned, it was an important one. The troops and planes that were lost in that abortive campaign had all been drawn from our already overstretched forces in the Western Desert, and as a result those forces were now diminished to such an extent that for the next two years our desert army suffered defeat after defeat and Rommel was at one time actually threatening to capture Egypt and the whole of the Middle East. It took two years to rebuild the Desert Army to a point where the Battle of Alamein

could be won and the Middle East secured for the rest of the war.

The handful of pilots who survived the Grecian campaign were tremendously lucky. The odds were strongly against any of us coming out alive. The five who flew our remaining Hurricanes to Crete were to fight valiantly on the island when the Germans attacked a short time later with a massive airborne invasion. I know that one of them at least, Bill Vale from 80 Squadron, survived and escaped when the island was captured, and lived to fight again, but I do not know what happened to the others.

After they had taken Greece in May 1941, the Germans mounted a massive airborne invasion of Crete. They captured Crete and they also took the island of Rhodes, and after that, flushed with success, they turned their eyes towards the softest spots in all of the Middle East – Syria and the Lebanon. These spots were soft because they were controlled totally by a large and very efficient pro-German Vichy French army.

Most people know about the very great trouble the Vichy French fleet gave to Britain in 1941 after France had fallen. Our navy actually had to put the French warships out of action by bombarding them at Oran to make sure they didn’t fall into German hands. Most people know about that. But not many know about the chaos the Vichy French caused at the same time in Syria and the Lebanon. They were fanatically anti-British and pro-German, and if the Germans with their help had managed to get a foothold in Syria at that particular moment, they could have marched down into Egypt by the back door. The Vichy French had therefore to be dislodged from Syria as soon as possible.

The Syrian Campaign, as it was called, started up almost immediately after Greece, and a very considerable army composed of British and Australian troops was sent up through Palestine to fight the disgusting pro-Nazi Frenchmen. This small war was a bloody affair in which thousands

of lives were lost, and I for one have never forgiven the Vichy French for the unnecessary slaughter they caused.

Air cover for our army and navy in this campaign was to be provided by the remnants of good old 80 Squadron, and about a dozen new Hurricanes were speedily brought out from England to replace the ones lost in Greece. I began to see now why it had been important to get us pilots out of the Grecian mess alive, even without our planes. It takes longer to train a pilot than it does to build an aeroplane. Mind you, it would have made even more sense to have saved some of those Grecian Hurricanes as well as the pilots, but that didn’t happen.

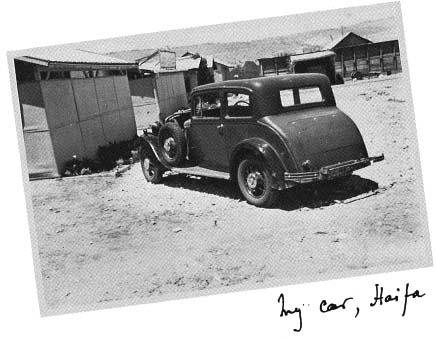

Eighty Squadron were to assemble at Haifa in northern Palestine in the last week of May 1941. Each pilot was told to collect his new Hurricane at Abu Suweir on the Suez Canal and fly it to Haifa aerodrome. I asked Middle East Fighter Command if someone else could fly my plane to Haifa for me because I wanted to drive myself up there in my own motor-car. I had become the very proud possessor of a nine-year-old 1932 Morris Oxford saloon, a machine whose body had been sprayed with a noxious brown paint the colour of canine faeces, and whose maximum speed on a straight and level track was thirty-five miles per hour. With some reluctance Fighter Command granted my request.

There was a ferry across the Suez Canal at Ismailia. It was simply a wooden float that was pulled from one bank to the other by wires, and I drove the car on to it and was taken to the Sinai bank. But before I was allowed to start the long and lonely journey across the Sinai Desert, I had to show the officials that I had with me five gallons of

spare petrol and a five-gallon can of drinking water. Then off I went.

I loved that journey. I loved it, I think, because I had never before in my life been totally without sight of another human being for a full day and a night. Few people have. There was a single narrow strip of hard road running through the soft sands of the desert all the way from the Canal up to Beersheba on the Palestine border. The total distance across the desert was about 200 miles and there was not a village or a hut or a shack or any sign of human life over the entire distance. As I went chugging along through this sterile and treeless wasteland, I began to wonder how many hours or days I would have to wait for another traveller to turn up if my old car should break down.

I was soon to find out. I had been going for some five hours when my radiator began to boil over in the fierce afternoon heat. I stopped and opened the bonnet and waited for everything to cool down. After an hour or so I was able to remove the radiator cap and pour in some more water, but I realized that it would be pointless to drive on again in the full heat of the sun because the engine would simply boil over once more. I must wait, I told myself, until the sun had gone down. But there again I knew I must not drive at night because my headlights did not work and I was certainly not going to run the risk of sliding off the narrow hard strip in the dark and getting bogged down in soft sand. It was a bit of a dilemma and the only way out of it that I could see would be to wait until dawn and make a dash for Beersheba before the sun began to roast my engine again.

I had brought a large water-melon with me as emergency

rations, and now I cut a chunk out of it and flipped away the black seeds with the point of my knife and ate the lovely cool pink flesh standing beside the car in the sun. There was no shade anywhere except inside the car, but in there it was like an oven. I longed for a parasol or anything else that would give me a little shade, but I had nothing. I was wearing khaki shorts and a khaki shirt and I had a blue RAF cap on my head. I found a rag and soaked it in the tepid drinking water and draped it over my head and put the cap over it. That helped. I walked slowly up and down the boiling hot strip of road and kept gazing in absolute wonder at the amazing landscape that surrounded me. There was the blazing sun, the vast hot sky, and beneath it all on every side a great pale sea of yellow sand that was not quite of this world. There were mountains now in the distance on the right-hand side of the road, pale Tanagra-coloured mountains faintly glazed with blue that rose up suddenly out of the desert and faded away in a haze of heat against the sky. The stillness was overpowering. There was no sound at all, no voice of bird or insect anywhere, and it gave me a queer godlike feeling to be standing there alone in such a splendid hot inhuman landscape – as though I were on another planet, on Jupiter or Mars, or in some place more desolate still, where never would the grass grow green nor a rose bloom red.

I kept pacing slowly up and down the road, waiting for the sun to go down and for the cool night to come along. Then suddenly, in the sand just a foot or so off the road, I saw a giant scorpion. Jet black she was and fully six inches long, and clinging to her back, like passengers on the top of an open bus, were her babies. I bent a little closer to

count them. One, two, three, four, five … there were fourteen of them altogether! At that point she saw me. I am quite sure I was the first human she had ever seen in her life, and she curled her tail up high over her body with the pincers wide open, ready to strike in defence of her family. I stepped back a pace but continued to watch her, fascinated. She scuttled over the sand and disappeared into a hole that was her burrow.

When the sun went down, it became dark almost at once, and with the night came a blessed and dramatic drop in temperature. I ate another hunk of water-melon, drank some water and then curled up as best I could in the back seat of the car and went to sleep.

I started off again the next morning at first light, and in another couple of hours I had crossed the desert and

come to Beersheba. I drove on northwards across Palestine, through Jerusalem and Nazareth, and in the late afternoon I skirted Mount Carmel and dropped down into the town of Haifa. The aerodrome was outside the town on the edge of the sea, and I drove my old car in triumph past the guard at the gates and parked it alongside the officers’ mess, which was a small hut made of wood and corrugated iron.

We had nine Hurricanes at Haifa and the same number of pilots, and in the days that followed we were kept very busy. Our main job was to protect the navy. Our navy had two large cruisers and several destroyers stationed in Haifa harbour and every day they would sail up the coast past Tyre and Sidon to bombard the Vichy French forces in the mountains around the Damour river. And whenever our

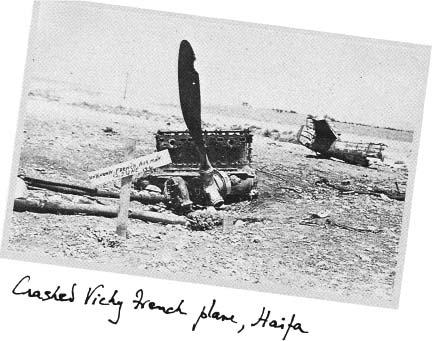

ships came out, the Germans came over to bomb them. They came from Rhodes, where they had built up a strong force of Junkers Ju 88s, and just about every day we met those Ju 88s over the fleet. They came over at 8,000 feet and we were usually waiting for them. We would dive in amongst them, shooting at their engines and getting shot at by their front- and rear-gunners, and the sky was filled with bursting shells from the ships below and when one of them exploded close to you it made your plane jump like a stung horse. Sometimes the Vichy French air force joined up with the Germans. They had American Glenn Martins and French Dewoitines and Potez 63s, and we shot some of them down and they killed four of our nine pilots. And then the Germans hit the destroyer

Isis

and we spent the whole day circling above her in relays and fighting off the Ju 88s while a naval tug towed her back to Haifa.