gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (24 page)

There is a strange echo of this scenario in the Scandinavian story of Ragnarök. The main battle is most often described with Odin coming up against Loki’s son, the Fenris Wolf, and losing his life, and then how Odin’s son Víðarr is finally able to kill the demonic creature. However, less attention is paid to the story of the Germanic, Old English, and Norse war god named Tíw, Týr, or Tir. He is willing to sacrifice his life to ensure the safety of humankind by placing his arm in the Fenris Wolf ’s jaws after the gods had asked the beast to try on various fetters, or shackles, to test his strength against them, the real purpose being to trick Fenris into bondage so that he could never wreak havoc in the world (see figure 16.1).

Fenris was easily able to break free of two sets of fetter, the second one twice as strong as the first. Yet he becomes suspicious when he sees the next fetter, which seems to be little more than a silk ribbon. So to make sure this is not a ruse, Fenris asks one of the gods to step forward and put his arm in his mouth. Tíw agrees to do so, after which the wolf is bound.

Figure 16.1. Helmet plate die from Torslunda on Oland in Sweden showing the Norse god Tíw binding the Fenris Wolf, seventh century AD .

Of course, it

is

a trick, as the silk ribbon has been forged by dark elves from six different magical substances, which when combined make an utterly unbreakable fetter. Once the Fenris Wolf realizes he has been tricked, he bites off Tíw’s right arm.

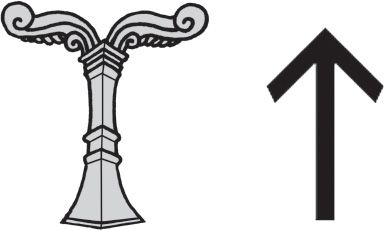

Although simply a tale, it is a story containing much deeper symbolism relating to the stability of the world, and in particular the world pillar. In the Norse magical alphabet known as the runes, Tíw is represented by the T-rune named Tiwaz

.

It is composed of an upright pole at the top of which are two downward turned lines that show the rune to be an arrow. The Tiwaz rune is popularly considered to be a representation of the

“

vault of heaven held up by the universal column,”

2

as well as the Irminsul, the “world column” of the Saxons, that “has its heavenly termination in the pole star.”

3

(See figure 16.2.)

Figure 16.2. Left, the German world pillar known as the Irminsul and, right, the Tiwaz rune, showing its likeness to the world pillar.

This identification fits well with Tíw’s role as personification of the North Star, suggesting that originally he was the genius loci, or guardian spirit, of the axis mundi, protecting it against attacks by adversaries such as the Fenris Wolf. Even though Tíw is killed by the helldog Garm in the

Prose Edda

rendition of Ragnarök, in the

Poetic Edda

this act is never fulfilled—Tíw’s earlier sacrifice for his warriors and humanity permitting him the title “Leavings of the Wolf ”

4

; in other words, the one that the wolf left alone, that is, didn’t kill.

SAVIOR OF THE WORLD

Tíw was a very early sky god. His name is thought to derive from the same route as

deus,

or

dei,

meaning “god,”

5

although he is also the “hanged” god. This suggests he is to be seen as some kind of savior who fought and won the battle against the cosmic trickster in the guise of a supernatural wolf, when it attacked the world pillar and almost brought about the destruction of not only the Æsir gods, but also humankind, an abstract memory, seemingly, of a very real comet impact event in some former age.

In Nordic folklore the twin streams formed by the Milky Way’s Great Rift, in the vicinity of Cygnus, have been identified as the “two streams of saliva” that fall from the Fenris Wolf ’s jaws, one named Wil, the other called Wan, or Van, known also as “Hell’s stream” or the “road of the dead”

6

(see figure 15.1 on p. 138). Fenris’s alternative name, Vanargandr, actually means monster guardian of the River Van,

7

so there is tantalizing evidence that the wolf was linked in some manner with the Milky Way’s Great Rift, and through this to the celestial pole and axis mundi, from which the monster was finally able to break free of his bonds to wreak havoc in the world.

BLACK DOG

And the Fenris Wolf was not the only supernatural canid of European folklore to have been perceived as a threat to the stability of the world pillar. Ukrainian sky lore relates how the constellation of Ursa Major, which includes the seven stars making up the Plough or Big Dipper, is a team of horses tethered to a harness and that “every night a black dog tries to bite through the harness, in order to destroy the world, but he does not achieve his disastrous aim: at dawn, when he runs to drink from a spring, the harness renews itself.”

8

Since the Big Dipper circles around the celestial pole, the horses tethered to the sky pole are the method by which the heavens turn. The “black dog” is, of course, the cosmic trickster attempting to break the horses free in order to collapse the sky pole and bring about the destruction of the world.

Variations of the Ukrainian sky myth say that the black dog was bound in chains beside the constellation of Ursa Minor, the Little Bear, which is the location of the current Pole Star, Polaris. Here the animal attempts to gnaw through its shackles, and when this occurs the world will end,

9

a clear comparison with the actions of the Fenris Wolf in Norse sky lore.

THE ETERNAL STRUGGLE

In a similar vein, Russian philologist Dr. Vyacheslav Ivanov wrote that the eternal struggle against the dragon in Slavonic folklore derives from a much older tradition in which heroic blacksmiths were able to bind and chain “a terrible dog.” Ivanov goes on to say that “over the whole territory of Eurasia, this mythological complex is associated . . . with the Great Bear . . . (and) with a star near it as a dog which is dangerous for the Universe.”

10

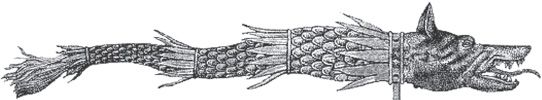

Figure 16.3. Dacian battle standard known as the Draco, or Drago. Note its cometlike tail.

Although it’s not stated which star “near” Ursa Major the infernal dog is to be identified with, almost certainly it is Alcor, the Fox Star, or Wolf Star. It is a conclusion confirmed by the fact that this canine “is dangerous for the Universe” and has the ability to bring about the destruction of everything. As sky monsters, the wolf and dragon are essentially one and the same, as is shown by the battle standard of the Dacians, the pre-Roman peoples of Romania. With a wolf ’s head and serpent-like tail, it is called the Draco, or Drago, the dragon, and has been identified as a possible representation of a comet (see figure 16.3).

11

TEUTONIC MYTHOLOGY

The great philologist and mythologist Jacob Grimm (1785–1863) in his multivolume work

Teutonic Mythology

discusses the role of the supernatural canid in catastrophe folklore. He saw the Fenris Wolf as quite simply the trickster god Loki “in a second birth . . . (although now) in the shape of a wolf.”

12

Grimm cites also an old Scottish story about “the tayl of the wolfe and the warldis end,”

13

a reference to the world falling apart following the appearance of a wolf ’s tail, which we can be pretty sure is a metaphor for a comet. Grimm wrote that much fuller stories of how a great wolf or dog had brought destruction to the world must once have existed “all over Germany, and beyond it,” adding that, “we still say, when baneful and perilous disturbances arise, ‘the devil is broke loose,’ while in the North they would say

‘Loki

er or böndum (Loki is out of control).’”

14

Grimm quotes other examples of catastrophe-based folklore and folk beliefs among the peoples of medieval Europe. They include a popular French song about King Henry IV that “expresses the far end of the future as the time when the wolf ’s teeth shall get at the moon”

15

; in other words, the wolf will cause it to be extinguished, bringing about the world’s end. All these stories seem to be fragmented memories of a terrible cataclysm, coupled with an unerring fear that one day it could all happen again.

THE BUNDAHISHN

That these examples of canine cosmic tricksters, manifesting in the skies as planet killers such as comets and asteroids, come from Europe and not Anatolia need not concern us, for similar cosmological themes exist in sky lore much closer to Göbekli Tepe. The Bundahishn, a sacred text of Zoroastrianism, a religious doctrine that once thrived in Iran, India, and Armenia, contains its own graphic account of a Ragnarök-style scenario, which includes the following somewhat enigmatic lines: “As Gokihar falls in the celestial sphere from a moon-beam on to earth, the distress of the earth becomes such-like as that of a sheep when a wolf falls upon it.”

16

Gokihar

is generally translated as “meteor,”

17

that is, an incoming comet fragment, asteroid, or bolide of some sort, while the name itself has been interpreted as meaning “wolf progeny.”

18

The double allusion in this statement to the wolf is significant, and one can envisage, and even feel, the force of the assumed impact, here likened to the manner that a sheep’s legs bend and collapse when pounced on by a wolf.

That Gokihar’s appearance heralds some kind of apocalyptic event seems confirmed in the verse that follows: “Afterward, the fire and halo melt the metal of [the archangel] Shatvairo, in the hills and mountains, and it [the molten metal] remains on this earth like a river.”

19

If the impact of a comet fragment or asteroid

is

implied, then the presence afterward of firestorms and rivers of molten “metal” caused by the eruption of volcanoes would be inevitable.

After the destruction of the seven evil spirits under the rule of the evil principle, named Ahriman, Gokihar “burns the serpent in the melted metal, and the stench and pollution which were in hell are burned in that metal, and it (hell) becomes quite pure.”

20

Once again these are indications that Gokihar, the “wolf progeny,” is involved directly with apocalyptic events described in the Bundahishn, and although they focus on a day of reckoning for both the gods and humanity, there is a sense of them forming part of a repeating cycle. In other words, the Bundahishn describes a replay of events that have already taken place. Christians in countries where the Norse myths remained strong associated the events of Ragnarök with the coming Day of Judgment, described in the book of Revelation; in other words, they saw them as events to come, not events that had occurred during some previous age.