Gimme Something Better (41 page)

Read Gimme Something Better Online

Authors: Jack Boulware

Greg Valencia:

At that time, Neurosis was the shit. They were the big Bay Area love.

At that time, Neurosis was the shit. They were the big Bay Area love.

Anna Brown:

My dad thought it was funny that my favorite band was called Neurosis. He was the head of the psychiatric unit at the hospital. So Dave Ed gave him a Neurosis T-shirt and he wore it to the hospital Christmas party. He thought that was hilarious.

My dad thought it was funny that my favorite band was called Neurosis. He was the head of the psychiatric unit at the hospital. So Dave Ed gave him a Neurosis T-shirt and he wore it to the hospital Christmas party. He thought that was hilarious.

Noah Landis:

Christ on Parade was intense, but we were fast and we had hooks. What Neurosis was doing was a lot darker, a lot deeper and a lot

meaner

. During that time, Neurosis was broadening its idea of what they were doing.

Christ on Parade was intense, but we were fast and we had hooks. What Neurosis was doing was a lot darker, a lot deeper and a lot

meaner

. During that time, Neurosis was broadening its idea of what they were doing.

Jeff Ott:

Both Christ on Parade and Neurosis started to head in a direction of intentionally doing dissonant music. But Neurosis was also about complicated songwriting and musicianship. The drive was, “Let’s go further out than this.” They were never going to find a formula and stick with it.

Both Christ on Parade and Neurosis started to head in a direction of intentionally doing dissonant music. But Neurosis was also about complicated songwriting and musicianship. The drive was, “Let’s go further out than this.” They were never going to find a formula and stick with it.

Scott Kelly:

Christ on Parade’s last show at Gilman never fucking happened because of us. The fuckin’ fights were so bad that they had to shut down the show.

Christ on Parade’s last show at Gilman never fucking happened because of us. The fuckin’ fights were so bad that they had to shut down the show.

Ben Sizemore:

It disintegrated into a big brawl. It seemed like every asshole skinhead in the Bay Area showed up. Econochrist played that show, and some skinhead girl with a fringe jumped up onstage while we were playing and tried to hit me. Neurosis was supposed to play right before Christ on Parade, and they couldn’t get through a song without a fight breaking out. I remember Scott so famously saying, “Alright! Next fucking fight that breaks—” and of course a fight broke out. They stopped playing and then it spilled out onto the street, and before you knew it, the cops were there and the show was shut down. Christ on Parade never got to play their last show at Gilman. Later that night, they played at their house for 20 people instead of 600. By that point, most of them were living in a house by the Oakland Greyhound station.

It disintegrated into a big brawl. It seemed like every asshole skinhead in the Bay Area showed up. Econochrist played that show, and some skinhead girl with a fringe jumped up onstage while we were playing and tried to hit me. Neurosis was supposed to play right before Christ on Parade, and they couldn’t get through a song without a fight breaking out. I remember Scott so famously saying, “Alright! Next fucking fight that breaks—” and of course a fight broke out. They stopped playing and then it spilled out onto the street, and before you knew it, the cops were there and the show was shut down. Christ on Parade never got to play their last show at Gilman. Later that night, they played at their house for 20 people instead of 600. By that point, most of them were living in a house by the Oakland Greyhound station.

Scott Kelly:

These guys loved to fight to our music. It was a fucking disease that we just couldn’t get rid of. We had to show up at gigs with our own security. We had a couple of guys that I worked with who were ’Nam vets, special ops guys.

These guys loved to fight to our music. It was a fucking disease that we just couldn’t get rid of. We had to show up at gigs with our own security. We had a couple of guys that I worked with who were ’Nam vets, special ops guys.

Then we added keyboards. It wasn’t a conscious move to eliminate the violence from the shows, but those guys didn’t want anything to do with that. It was the funniest thing. Add keyboards, the fight’s over. When we showed up with keyboards, people left before we’d even played a note.

Noah Landis:

People were pissed. They were into Neurosis because it was the most intense hardcore band in the area. Then they put a keyboard out there and this new guy that nobody knew. People were just totally bummed. They were hurling insults, they were calling them Faith No More.

People were pissed. They were into Neurosis because it was the most intense hardcore band in the area. Then they put a keyboard out there and this new guy that nobody knew. People were just totally bummed. They were hurling insults, they were calling them Faith No More.

I stood there on the side of the stage watching this irate crowd. Unfortunately, it just took the guy forever to set up the keyboard. It felt like it was never gonna end, because he was building this whole contraption with little monkey bars. It was painful to witness.

Davey Havok:

When Neurosis busted out the keyboard, it was like, “What are they, fuckin’ Flock of Seagulls?” It confused people. It was no longer punk rock because—ignoring the Screamers or Suicide—punk rock didn’t have keyboards. Neurosis was serious and brutal and dark and heavy and hard. And keyboards didn’t fit into the perception people had of Neurosis. Which was a shame.

When Neurosis busted out the keyboard, it was like, “What are they, fuckin’ Flock of Seagulls?” It confused people. It was no longer punk rock because—ignoring the Screamers or Suicide—punk rock didn’t have keyboards. Neurosis was serious and brutal and dark and heavy and hard. And keyboards didn’t fit into the perception people had of Neurosis. Which was a shame.

Noah Landis:

For years there was a huge divide in the Neurosis fans. There were people who only listened to the first two albums, and everything after was crap. Anything with keyboards was crap.

For years there was a huge divide in the Neurosis fans. There were people who only listened to the first two albums, and everything after was crap. Anything with keyboards was crap.

Scott Kelly:

Gilman was definitely our place for awhile. We played opening weekend and three of the first four benefits. Then, around ’91, when

Souls at Zero

came out, they decided that we weren’t punk enough to play there. They passed judgment on us the same time

Maximum RocknRoll

did. I remember calling up Tim, “Why won’t you review us in your magazine anymore?”

Gilman was definitely our place for awhile. We played opening weekend and three of the first four benefits. Then, around ’91, when

Souls at Zero

came out, they decided that we weren’t punk enough to play there. They passed judgment on us the same time

Maximum RocknRoll

did. I remember calling up Tim, “Why won’t you review us in your magazine anymore?”

“Well, you guys aren’t punk rock. You guys are like fuckin’ Yes. You play like ten-minute songs.”

“What’s the definition of punk rock?”

“Three chords and a cloud of dust, Scott.”

It was so funny. I was like, man, you’re a fuckin’ hardheaded old bastard. But I respected that. In a way, it freed us from that entire dogmatic political scene. Which, in my opinion, never had anything to do with music.

Noah Landis:

Simon, their keyboard player, wasn’t involved in New Method or punk rock. He didn’t share any of that history with the band. He was a guy with a keyboard that Steve knew from the South Bay. They couldn’t hack it with him. When they came home from the tour, they kicked him out.

Simon, their keyboard player, wasn’t involved in New Method or punk rock. He didn’t share any of that history with the band. He was a guy with a keyboard that Steve knew from the South Bay. They couldn’t hack it with him. When they came home from the tour, they kicked him out.

Scott Kelly:

We quickly absorbed Noah. There were no walls.

We quickly absorbed Noah. There were no walls.

Noah Landis:

I said yes because it was bigger than any band I’d ever been in by that point, really powerful and unique. They were my best and oldest friends and I wanted to make music with them. But I was also on drugs. The early ’90s were the darkest years in my life, as far as getting into speed and losing that ability to care about yourself or the person you’re with. Everything becomes, “Fuck it!” Except your friends who are doing drugs with you.

I said yes because it was bigger than any band I’d ever been in by that point, really powerful and unique. They were my best and oldest friends and I wanted to make music with them. But I was also on drugs. The early ’90s were the darkest years in my life, as far as getting into speed and losing that ability to care about yourself or the person you’re with. Everything becomes, “Fuck it!” Except your friends who are doing drugs with you.

I got a sampler and a keyboard and hung out with Scott, both of us just tweaked to the gills, pathetically pushing buttons. I felt like maybe I can’t do this, maybe I’ve challenged myself beyond my ability. It was terrifying. Like being boiled in water or something. But I figured it out. Then things got really creative.

Kate Knox:

Neurosis was one of the first bands that had that slower—what I call napcore.

Neurosis was one of the first bands that had that slower—what I call napcore.

Scott Kelly:

We thought we can do whatever the fuck we want. Are we playing that too long? Well, it feels good to me, who gives a shit? Slow? Fast? It didn’t matter. We fed off each other.

We thought we can do whatever the fuck we want. Are we playing that too long? Well, it feels good to me, who gives a shit? Slow? Fast? It didn’t matter. We fed off each other.

A. C. Thompson:

I saw them in San Francisco. It was this totally mind-blowing, dark Bacchanalian event. You expected to see people killing one another or fucking each other in a mass orgy on the floor. You thought it might actually happen. They were so cinematic. It was like heavy soundtrack music.

I saw them in San Francisco. It was this totally mind-blowing, dark Bacchanalian event. You expected to see people killing one another or fucking each other in a mass orgy on the floor. You thought it might actually happen. They were so cinematic. It was like heavy soundtrack music.

Noah Landis:

We’ve been doing this for so long, together through great times and hard times. Through children and divorces and marriages and serious losses.

We’ve been doing this for so long, together through great times and hard times. Through children and divorces and marriages and serious losses.

Scott Kelly:

And we’re still doing our own thing. We put out our own records, we book our own shows. We learned to do that from the people who did it before us and showed us how. We’re holding the torch for that.

And we’re still doing our own thing. We put out our own records, we book our own shows. We learned to do that from the people who did it before us and showed us how. We’re holding the torch for that.

Ben Saari:

When I hear the name Neurosis, I get . . . It’s sort of how I feel about my early girlfriends. Like every really important period of my life.

When I hear the name Neurosis, I get . . . It’s sort of how I feel about my early girlfriends. Like every really important period of my life.

32

Sleep, What’s That?

Andy Asp:

Hardcore might have been really refreshing and exciting the first couple years, but nobody wanted to call themselves a punk band anymore. Punk became kind of this dirty word.

Hardcore might have been really refreshing and exciting the first couple years, but nobody wanted to call themselves a punk band anymore. Punk became kind of this dirty word.

Jesse Michaels:

In the early ’80s there were fights at every show. People stood around and watched people kick the shit out of each other. You hear all these people talking about the hardcore days, how great it was. How great is watching five people beat one person up?

In the early ’80s there were fights at every show. People stood around and watched people kick the shit out of each other. You hear all these people talking about the hardcore days, how great it was. How great is watching five people beat one person up?

Then there was a dead period. This little pocket of weird kids were getting into punk, and it actually was a very creative and open thing happening.

Frank Portman:

Crimpshrine was a strange marriage between Jeff Ott, who was the crazy voice and as close to a modern-day hippie as you could get, and Aaron Elliott, this really great writer who wrote the lyrics and was the drummer. Not really derived from anything. Destined for self-destruction, but this brilliance behind it.

Crimpshrine was a strange marriage between Jeff Ott, who was the crazy voice and as close to a modern-day hippie as you could get, and Aaron Elliott, this really great writer who wrote the lyrics and was the drummer. Not really derived from anything. Destined for self-destruction, but this brilliance behind it.

Jeff Ott:

Everything was very masculine then, and very angry and aggressive. What we did took punk rock into a very watered-down direction. People went, “Oh, that’s melodic. It doesn’t have to be all this angry, dissonant thing.”

Everything was very masculine then, and very angry and aggressive. What we did took punk rock into a very watered-down direction. People went, “Oh, that’s melodic. It doesn’t have to be all this angry, dissonant thing.”

Anna Brown:

Jeff Ott was like a messiah. A strong sense of justice. A born preacher. Very charismatic and very confident about the ways of the world, lots of ideas about things. Some of his ideas were just nuts, but compellingly crazy. Jeff took a

lot

of acid.

Jeff Ott was like a messiah. A strong sense of justice. A born preacher. Very charismatic and very confident about the ways of the world, lots of ideas about things. Some of his ideas were just nuts, but compellingly crazy. Jeff took a

lot

of acid.

Jesse Michaels:

Me and my friends followed Crimpshrine all over the place. They were a huge influence.

Me and my friends followed Crimpshrine all over the place. They were a huge influence.

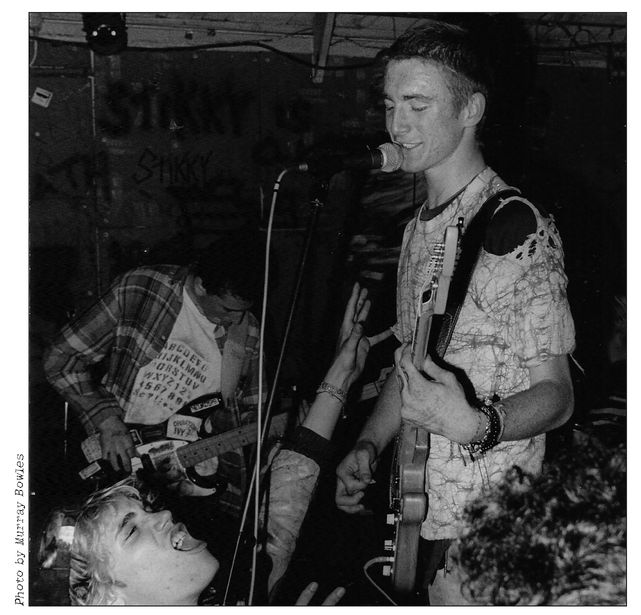

Quit Talkin’ Claude: Jesse Michaels singing along with Crimpshrine’s Jeff Ott

Jeff Ott:

I grew up in Berkeley. When I was 10 or 11, I met John Kiffmeyer and Aaron Cometbus. Dave Edwardson lived a few blocks away up in the Berkeley Hills with his parents. Arnie from my soccer team, his father was Wes Robinson, who ran Ruthie’s Inn. We’d end up at soccer team functions at my house, and Wes would be checking me out, listening to Journey. He told me, “Dude, you should check out Motörhead.”

I grew up in Berkeley. When I was 10 or 11, I met John Kiffmeyer and Aaron Cometbus. Dave Edwardson lived a few blocks away up in the Berkeley Hills with his parents. Arnie from my soccer team, his father was Wes Robinson, who ran Ruthie’s Inn. We’d end up at soccer team functions at my house, and Wes would be checking me out, listening to Journey. He told me, “Dude, you should check out Motörhead.”

John Fogerty’s kids hung out with us. They’re the reason I started getting high. After the band [Creedence] broke up, John Fogerty lived in between Dave Edwardson’s house and my house. He had a band called Ruby, who played for my third-grade class. I thought they were great ’cause I had never seen live music before.

I was a straight-A student, and in between 13 and 15, I got expelled. Did some back and forth in terms of living with my family. My parents were fairly checked out anyway. They were just interested in viticulture and drinking the by-products of it, namely.

Aaron Cometbus:

A lot of us, like Noah Landis, Dave Ed, Jesse Michaels, Tim Armstrong and me, we’d grown up together and played in each other’s bands. Most of the bands never even played shows, but they were still in the scene reports in early issues of

Cometbus

and they were on the compilation tapes I put out.

A lot of us, like Noah Landis, Dave Ed, Jesse Michaels, Tim Armstrong and me, we’d grown up together and played in each other’s bands. Most of the bands never even played shows, but they were still in the scene reports in early issues of

Cometbus

and they were on the compilation tapes I put out.

Ben Saari:

I think it was Aaron Elliott, Jesse Michaels and Jeff Ott, they were called Trampled by Fish. And then Jesse went out to the East Coast, so it was just Aaron and Jeff, and they were shopping for a third wheel forever. It was Tim Armstrong for awhile.

I think it was Aaron Elliott, Jesse Michaels and Jeff Ott, they were called Trampled by Fish. And then Jesse went out to the East Coast, so it was just Aaron and Jeff, and they were shopping for a third wheel forever. It was Tim Armstrong for awhile.

Jeff Ott:

We had this weird bassist guy who turned out to be in disguise. Had a wig that was like glued. And then he disappeared. Shortly after that we found Pete at Berkeley High, and it became Crimpshrine. The first show was at New Method. We’d all go across the street and get high, and there was this girl who crimped her hair all the time, I believe her name was Maya.

We had this weird bassist guy who turned out to be in disguise. Had a wig that was like glued. And then he disappeared. Shortly after that we found Pete at Berkeley High, and it became Crimpshrine. The first show was at New Method. We’d all go across the street and get high, and there was this girl who crimped her hair all the time, I believe her name was Maya.

Lenny Filth:

Crimped-out fuckin’ blond hair that was just gorgeous. Aaron had a crush on her, but he never went up and talked to her.

Crimped-out fuckin’ blond hair that was just gorgeous. Aaron had a crush on her, but he never went up and talked to her.

Jeff Ott:

Aaron was like, “We should call the band Crimpshrine.” And basically named the band after her hair. This was like ’84. I imagine by now somebody’s told her there’s this band named after her.

Aaron was like, “We should call the band Crimpshrine.” And basically named the band after her hair. This was like ’84. I imagine by now somebody’s told her there’s this band named after her.

We played New Method, Own’s Pizza, the Farm. We played shows with Soup at the Unitarian Universalist churches in Kensington and Albany. Always at Unitarian churches, though, ’cause they’re all communists.

Ben Saari:

They really personalized a lot of the songwriting. Until that point, people had been writing about the big outside world. They were more introverted and introspective.

They really personalized a lot of the songwriting. Until that point, people had been writing about the big outside world. They were more introverted and introspective.

Anna Brown:

These incredibly impassioned lyrics that were about getting through life, about hope and despair at the same time. They were really catchy and raw. When you listen to them now, they’re still great.

These incredibly impassioned lyrics that were about getting through life, about hope and despair at the same time. They were really catchy and raw. When you listen to them now, they’re still great.

Jesse Michaels:

And they were just fun to watch. The shows were really small. It was almost more like parties more than real shows.

And they were just fun to watch. The shows were really small. It was almost more like parties more than real shows.

Anna Brown:

Jeff was really tall, thin, bald. You’d see him with this blood running down his head from shaving his head in the bathroom.

Jeff was really tall, thin, bald. You’d see him with this blood running down his head from shaving his head in the bathroom.

Rachel Rudnick:

Jeff Ott would take a Bic lighter and burn the excess hair off so it’d be like an inch long. It smelled so bad. He also griped about his older brother, who was a football player. I remember being on the bus and Jeff bragging that he had found the life insurance papers his parents had taken out on their kids, and his was twice as much as his brother.

Jeff Ott would take a Bic lighter and burn the excess hair off so it’d be like an inch long. It smelled so bad. He also griped about his older brother, who was a football player. I remember being on the bus and Jeff bragging that he had found the life insurance papers his parents had taken out on their kids, and his was twice as much as his brother.

Aaron Cometbus:

It was still a small town and you spent a lot of time just waiting for someone to arrive from out of town and make things more interesting. It was either runaways or people looking to buy large quantities of acid to bring back to wherever they were from. And the punks were involved in that, too. Acid was very much tied into the character and the economy of the scene. It was the main pastime and probably the main livelihood as well.

It was still a small town and you spent a lot of time just waiting for someone to arrive from out of town and make things more interesting. It was either runaways or people looking to buy large quantities of acid to bring back to wherever they were from. And the punks were involved in that, too. Acid was very much tied into the character and the economy of the scene. It was the main pastime and probably the main livelihood as well.

Billie Joe Armstrong:

I lived in a house with Jeff Ott in Richmond. Tré lived there, too. There were a few college kids living there, but slowly the punks started to infiltrate. Everybody would be up all night on acid, and the students had to get up to go to school in the morning. Eventually, they moved out. I remember at one point we ran out of firewood, and Jeff starting chopping down the stairs outside the house. We just burned that.

I lived in a house with Jeff Ott in Richmond. Tré lived there, too. There were a few college kids living there, but slowly the punks started to infiltrate. Everybody would be up all night on acid, and the students had to get up to go to school in the morning. Eventually, they moved out. I remember at one point we ran out of firewood, and Jeff starting chopping down the stairs outside the house. We just burned that.

James Washburn:

The first time I ever saw Crimpshrine was in the basement at Jake Filth’s house. That was a fuckin’ awesome show. Aaron Elliott was just such a fuckin’ unusual drummer. Zero drummer type skills but a badass drummer at the same time. The guy’d sit down with pots and pans and just go off. I thought he was an asshole. I don’t remember why, but that was my impression. I always felt like, I’m from Pinole, and these guys are from Berkeley, so they’re cooler than me. We became accepted later.

The first time I ever saw Crimpshrine was in the basement at Jake Filth’s house. That was a fuckin’ awesome show. Aaron Elliott was just such a fuckin’ unusual drummer. Zero drummer type skills but a badass drummer at the same time. The guy’d sit down with pots and pans and just go off. I thought he was an asshole. I don’t remember why, but that was my impression. I always felt like, I’m from Pinole, and these guys are from Berkeley, so they’re cooler than me. We became accepted later.

Other books

Tinker Bell and the Great Fairy Rescue by Disney Book Group

Spinning by Michael Baron

Friends Forever by Danielle Steel

No Stars at the Circus by Mary Finn

Hidden Thrones by Scalzo, Russ

Summer Winds by Andrews & Austin, Austin

Blaize and the Maven: The Energetics Book 1 by Ellen Bard

Blood of Angels by Reed Arvin

The Art of Love by Lacey, Lilac