Gimme Something Better (21 page)

Read Gimme Something Better Online

Authors: Jack Boulware

Nils Frykdahl:

The Acid Rain Ensemble was the official name of our band. We started out playing Barrington’s wine dinners, which were big costumed affairs, so we dressed up in ridiculous outfits right from the get-go. Not necessarily good costumes, but certainly face paint and garbage bags or whatever we could come up with. That often spilled over into class. I remember meeting each other in the morning, “Hey, let’s wear garbage bags to school today.” And then we’d see each other between classes wearing garbage bags. Or wearing spikes up to the elbows in music class, just bristling. I hope that people are still doing retarded stuff around the UC Berkeley campus.

The Acid Rain Ensemble was the official name of our band. We started out playing Barrington’s wine dinners, which were big costumed affairs, so we dressed up in ridiculous outfits right from the get-go. Not necessarily good costumes, but certainly face paint and garbage bags or whatever we could come up with. That often spilled over into class. I remember meeting each other in the morning, “Hey, let’s wear garbage bags to school today.” And then we’d see each other between classes wearing garbage bags. Or wearing spikes up to the elbows in music class, just bristling. I hope that people are still doing retarded stuff around the UC Berkeley campus.

Dave Chavez:

Black Flag with Dez, Flipper and Sick Pleasure. That show was just insane. Somebody kicked in my speaker while we were playing and I got really upset. I had steel-toe boots on. So I just started kicking these bikes until they wrapped around a pole. It was in the air, the violence of the night. Everyone was acting like that. Everybody was pissed off and wanted to throw something. I’m surprised that nobody lit the place on fire. It was the craziest show probably of its time in Berkeley.

Black Flag with Dez, Flipper and Sick Pleasure. That show was just insane. Somebody kicked in my speaker while we were playing and I got really upset. I had steel-toe boots on. So I just started kicking these bikes until they wrapped around a pole. It was in the air, the violence of the night. Everyone was acting like that. Everybody was pissed off and wanted to throw something. I’m surprised that nobody lit the place on fire. It was the craziest show probably of its time in Berkeley.

Kareim McKnight:

A friend of ours got killed at Barrington. We believed that he was pushed by the cops. This was around the time that Bush Sr. was visiting San Francisco. He had helped us organize for that protest.

A friend of ours got killed at Barrington. We believed that he was pushed by the cops. This was around the time that Bush Sr. was visiting San Francisco. He had helped us organize for that protest.

Nils Frykdahl:

There were protest movements going on, some of them had their zines based out of Barrington. So there was the political edge and there was the musical, artistic edge, and some extra sort of edge because it was surrounded by this new conservatism within Berkeley.

There were protest movements going on, some of them had their zines based out of Barrington. So there was the political edge and there was the musical, artistic edge, and some extra sort of edge because it was surrounded by this new conservatism within Berkeley.

Kareim McKnight:

For a long time, Barrington Hall was at the center of the anti-Apartheid movement. We would meet at Barrington and organize, fill containers with gasoline. It was the ’80s, no one went anywhere without a can of spray paint.

For a long time, Barrington Hall was at the center of the anti-Apartheid movement. We would meet at Barrington and organize, fill containers with gasoline. It was the ’80s, no one went anywhere without a can of spray paint.

Nick Frabasilio:

The first issue of

Slingshot

was published at Barrington, as were all issues of the

Biko Plaza News

,

Slingshot

’s forerunner, during the anti-Apartheid sit-in.

The first issue of

Slingshot

was published at Barrington, as were all issues of the

Biko Plaza News

,

Slingshot

’s forerunner, during the anti-Apartheid sit-in.

Robert Eggplant:

Slingshot

gets its name from the Palestinian resistance people shooting slingshots against heavy artillery weapons.

Slingshot

gets its name from the Palestinian resistance people shooting slingshots against heavy artillery weapons.

PB Floyd:

The first issue was just one sheet of 11 × 17 white copier paper, folded in half. It was raw and militant, with handwritten headlines and hilarious seditious graphics.

Slingshot

looked like it was put together in the backseat of a getaway car after some really cool revolutionary act.

The first issue was just one sheet of 11 × 17 white copier paper, folded in half. It was raw and militant, with handwritten headlines and hilarious seditious graphics.

Slingshot

looked like it was put together in the backseat of a getaway car after some really cool revolutionary act.

Robert Eggplant:

One of the fights that the Slingshot Collective was involved with, besides diversity in education and homosexual rights, was trying to save Barrington.

One of the fights that the Slingshot Collective was involved with, besides diversity in education and homosexual rights, was trying to save Barrington.

During the fall [of 1989], with the war on drugs in full swing, students held a smoke-in on Sproul Plaza that attracted 2000, the largest event of the semester. Barrington Hall, a student co-op that helped organize the smoke-in and that had long provided a haven for activists and organizing efforts . . . was threatened with closure from a vote within the co-op system. There had been several other votes over the years to try to close Barrington and in November, the referendum passed.

—The People’s History of Berkeley

Kareim McKnight:

My friends at Barrington put out flyers and showed up at Sproul Plaza with shoeboxes full of shake joints. Of course, this massive crowd formed. It was a big spectacle. My brother was on the way to class and ended up on the front page of the

Daily Cal

, smoking a joint with a latte in his hand.

My friends at Barrington put out flyers and showed up at Sproul Plaza with shoeboxes full of shake joints. Of course, this massive crowd formed. It was a big spectacle. My brother was on the way to class and ended up on the front page of the

Daily Cal

, smoking a joint with a latte in his hand.

Nils Frykdahl:

There were always a lot of threats in that direction. Every year, “Oh, the council is voting to close . . .” And we’d all get up in arms and we’d go around to other co-ops and bring guitars like, “Hey, we’re from Barrington Hall and we’re here to sing some songs for you guys tonight while you eat dinner.” As a goodwill gesture.

There were always a lot of threats in that direction. Every year, “Oh, the council is voting to close . . .” And we’d all get up in arms and we’d go around to other co-ops and bring guitars like, “Hey, we’re from Barrington Hall and we’re here to sing some songs for you guys tonight while you eat dinner.” As a goodwill gesture.

Kareim McKnight:

The Barrington kids came around to all the other co-ops to make their plea. They were very emotional. I remember one kid saying, “Look, if we get killed, it’s on your hands.”

The Barrington kids came around to all the other co-ops to make their plea. They were very emotional. I remember one kid saying, “Look, if we get killed, it’s on your hands.”

Nils Frykdahl:

People really had exaggerated notions of what was going on there. They’d say, “Do you carry a gun? I hear everybody carries guns and it’s really dangerous.” Or, “I hear everybody’s addicted to heroin.” There was definitely plenty of drugs and plenty of ruined lives. So from the point of view of parents, it was a bad place. Kareim McKnight: The neighbors sued. They had a lot of documentation about the shows and the parties, people throwing washing machines off the roof.

People really had exaggerated notions of what was going on there. They’d say, “Do you carry a gun? I hear everybody carries guns and it’s really dangerous.” Or, “I hear everybody’s addicted to heroin.” There was definitely plenty of drugs and plenty of ruined lives. So from the point of view of parents, it was a bad place. Kareim McKnight: The neighbors sued. They had a lot of documentation about the shows and the parties, people throwing washing machines off the roof.

Finally in March [of 1990], a poetry reading was declared illegal by police who cleared the building by force. A crowd developed which built fires and resisted the police. Finally police attacked, badly beating and arresting many residents and bystanders and trashing the house. Eventually, the house was sold to a private landlord.

—The People’s History of Berkeley

Kareim McKnight:

I was told the police formed a gauntlet and beat all the kids as they ran down the hall when they came to throw the squatters out. I went to the courthouse to support all my comrades. We cheered when they were brought out in their jumpsuits. I was so sad to see it close. It’s a pathetic piece of nothing now.

I was told the police formed a gauntlet and beat all the kids as they ran down the hall when they came to throw the squatters out. I went to the courthouse to support all my comrades. We cheered when they were brought out in their jumpsuits. I was so sad to see it close. It’s a pathetic piece of nothing now.

Dean Washington:

Barrington Hall was like a rainbow in the sky, when you walked through that door. It was a beautiful place.

Barrington Hall was like a rainbow in the sky, when you walked through that door. It was a beautiful place.

Time is a crutch, eat mandarin oranges

—Graffiti from Barrington Hall

16

Grandma Rule

Sham Saenz:

All the girls in DMR wore these jean vests. That was their colors—jean vests that said “DMR.” Durant Mob Rules—Carol, Natasha and the twins.

All the girls in DMR wore these jean vests. That was their colors—jean vests that said “DMR.” Durant Mob Rules—Carol, Natasha and the twins.

Jason Lockwood:

They were the meanest people on the planet. They were just awful and they won’t deny it.

They were the meanest people on the planet. They were just awful and they won’t deny it.

Noah Landis:

Toni and Rachel ruled the scene. These two tiny, Hispanic-looking punk rock twins. Tiny! The scariest people I’d ever met. Some jock asshole would say something wrong and they would just charge him swingin’.

Toni and Rachel ruled the scene. These two tiny, Hispanic-looking punk rock twins. Tiny! The scariest people I’d ever met. Some jock asshole would say something wrong and they would just charge him swingin’.

Rachel DMR:

We hung out a lot. It sounds hokey now, but we were just kids. Durant and Telegraph was our stomping grounds. Silverball was the center of it. On the second level above Leopold’s Records, La Val’s Pizza and a coffee shop.

We hung out a lot. It sounds hokey now, but we were just kids. Durant and Telegraph was our stomping grounds. Silverball was the center of it. On the second level above Leopold’s Records, La Val’s Pizza and a coffee shop.

Jason Lockwood:

Runaway kids would hang out at La Val’s and eat leftover pizza. The girls’ bathroom was destroyed, almost solely the work of DMR.

Runaway kids would hang out at La Val’s and eat leftover pizza. The girls’ bathroom was destroyed, almost solely the work of DMR.

John Marr:

Silverball Gardens was a pinball hall. A lot of punk rock kids worked there.

Silverball Gardens was a pinball hall. A lot of punk rock kids worked there.

Kate Knox:

My boyfriend Dave Chavez, who played in Code of Honor and Verbal Abuse, he worked at Silverball. I remember sitting behind a desk with him and all of a sudden he ran out from behind the counter and busted this little kid. He had a quarter with a string on it, trying to play extra games. That was the first time I remember meeting Noah.

My boyfriend Dave Chavez, who played in Code of Honor and Verbal Abuse, he worked at Silverball. I remember sitting behind a desk with him and all of a sudden he ran out from behind the counter and busted this little kid. He had a quarter with a string on it, trying to play extra games. That was the first time I remember meeting Noah.

Noah Landis:

Basically I had drilled a hole through a quarter and attached it to a piece of thread. In some of the machines it would work. One time it got stuck and I was sitting there struggling with it—it was a lot of work to drill a hole through a quarter, I didn’t want to lose it. The guy busted me. Kate pointed at me and laughed. She just thought it was the funniest thing she’d ever seen.

Basically I had drilled a hole through a quarter and attached it to a piece of thread. In some of the machines it would work. One time it got stuck and I was sitting there struggling with it—it was a lot of work to drill a hole through a quarter, I didn’t want to lose it. The guy busted me. Kate pointed at me and laughed. She just thought it was the funniest thing she’d ever seen.

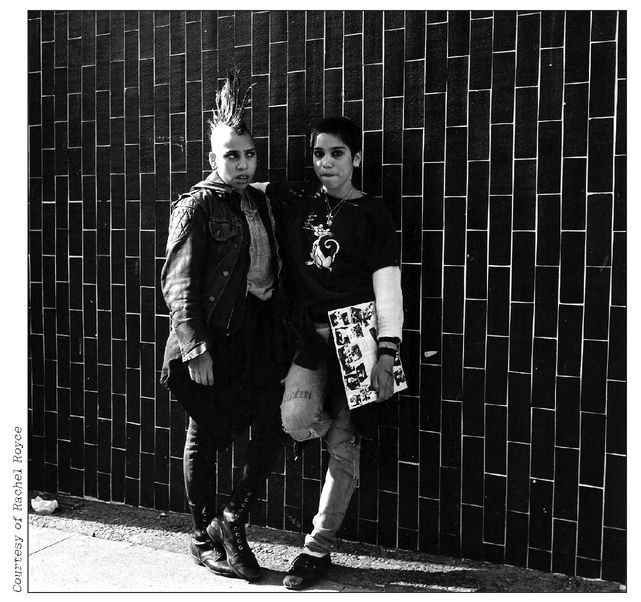

Scene Monitors: The DMR Twins on Telegraph

John Marr:

Apparently you could buy controlled substances from the change guy.

Apparently you could buy controlled substances from the change guy.

Noah Landis:

He carried it in those little fuse boxes. He would sell us the trimmings that came off the sheets of acid for like 30 cents a hit. Rachel DMR: There was a whole skater crowd, too. About half of us skated.

He carried it in those little fuse boxes. He would sell us the trimmings that came off the sheets of acid for like 30 cents a hit. Rachel DMR: There was a whole skater crowd, too. About half of us skated.

Toni DMR:

With skateboards as weapons you don’t have to be a strong, tough bitch to knock someone out. You just have to fuckin’ swing your arm.

With skateboards as weapons you don’t have to be a strong, tough bitch to knock someone out. You just have to fuckin’ swing your arm.

Rachel Rudnick:

The EBU. And the BTU. They would hang out.

The EBU. And the BTU. They would hang out.

Dean Washington:

Now, the BTU guys and my EBU guys didn’t always agree on things. There’d be times when there were physical acts of violence. Not always, but on a few occasions.

Now, the BTU guys and my EBU guys didn’t always agree on things. There’d be times when there were physical acts of violence. Not always, but on a few occasions.

Jim Lyon:

East Bay Underground was made up of people who skated and hung out at Blondie’s Pizza. Dean Washington is the founder. He was our social calendar.

East Bay Underground was made up of people who skated and hung out at Blondie’s Pizza. Dean Washington is the founder. He was our social calendar.

Ray Vegas:

East Bay Underground were just a bunch of drunk skater dudes, but they were mean guys.

East Bay Underground were just a bunch of drunk skater dudes, but they were mean guys.

Patrick Tidd:

BTU stands for Berkeley Trailers Union.

BTU stands for Berkeley Trailers Union.

Sammytown:

They were like the local biker gang, but they rode mountain bikes. They were like street thugs that rode bicycles.

They were like the local biker gang, but they rode mountain bikes. They were like street thugs that rode bicycles.

Kate Knox:

They were kind of the counterparts to DMR. Total drinker, fuck-up, get-crazy kinda guys.

They were kind of the counterparts to DMR. Total drinker, fuck-up, get-crazy kinda guys.

Toni DMR:

We were linked to BTU vicariously, through Rachel.

We were linked to BTU vicariously, through Rachel.

Patrick Tidd:

I met Rachel on Durant hanging out. I would see Rachel at shows. She and Toni were pretty out of control back then. Rachel on the run all of the time, Toni on the run half of the time. Those two got me in a lot of fights. I guess I fell in love with Rachel when I first met her.

I met Rachel on Durant hanging out. I would see Rachel at shows. She and Toni were pretty out of control back then. Rachel on the run all of the time, Toni on the run half of the time. Those two got me in a lot of fights. I guess I fell in love with Rachel when I first met her.

Dean Washington:

The DMR girls were nightmares. We didn’t look at them like they were hot chicks. They were a manly little bunch.

The DMR girls were nightmares. We didn’t look at them like they were hot chicks. They were a manly little bunch.

Rachel DMR:

We had big mouths—

We had big mouths—

Toni DMR:

—and steel-toe boots.

—and steel-toe boots.

Rachel DMR:

I had a chip on my shoulder. I was angry and pretty violent, and I drank a lot and did a lot of drugs and so did Toni. I look back at the anger and violence. It was almost primal. There was a rage that was almost existential. Like you’ve been getting beaten down your whole fucking life and then,

bam!

I had a chip on my shoulder. I was angry and pretty violent, and I drank a lot and did a lot of drugs and so did Toni. I look back at the anger and violence. It was almost primal. There was a rage that was almost existential. Like you’ve been getting beaten down your whole fucking life and then,

bam!

Dave Ed:

They were kinda scene monitors. Just completely fearless. I saw them fight sailors all the time at the On Broadway.

They were kinda scene monitors. Just completely fearless. I saw them fight sailors all the time at the On Broadway.

Jason Lockwood:

I watched Carol beat the crap out of people. Like a boxer. No wasted motion.

I watched Carol beat the crap out of people. Like a boxer. No wasted motion.

Paul Casteel:

The twins were sort of poster children for abuse. I think they were runaways for that reason.

The twins were sort of poster children for abuse. I think they were runaways for that reason.

Carol DMR:

There was a

People

magazine article about their abuse. I was in court as one of the witnesses when they were goin’ through all that. They flew in witnesses from Indonesia.

There was a

People

magazine article about their abuse. I was in court as one of the witnesses when they were goin’ through all that. They flew in witnesses from Indonesia.

Rachel DMR:

We had been abandoned in East Oakland as kids because our parents were drug addicts. We were discovered by neighbors and put into a foster home where we were abused. Then we were adopted when we were seven by a family. We lived in other countries earlier in our lives, but mostly we grew up in Berkeley. Our father was a professor of kinesiology. He was also a pedophile. Basically our father kept us locked away, until we finally rebelled at 14.

We had been abandoned in East Oakland as kids because our parents were drug addicts. We were discovered by neighbors and put into a foster home where we were abused. Then we were adopted when we were seven by a family. We lived in other countries earlier in our lives, but mostly we grew up in Berkeley. Our father was a professor of kinesiology. He was also a pedophile. Basically our father kept us locked away, until we finally rebelled at 14.

Carol DMR:

DMR started because a 13-year-old got raped walking home. We got together as a group of girls and made rules. The first rule was nobody walks home alone. That’s how it started. DMR was about sisterhood and trying to keep some type of order.

DMR started because a 13-year-old got raped walking home. We got together as a group of girls and made rules. The first rule was nobody walks home alone. That’s how it started. DMR was about sisterhood and trying to keep some type of order.

Rachel DMR:

The DMR girls consisted of Carol, me and Toni, Aileen Sullivan, Tasha Robinson, Emma Clarkson, Cathy Schulz, Kathy Harris, Wendy Orem, Robin Woolsey, Sarah Archbold and Kris Connolly.

The DMR girls consisted of Carol, me and Toni, Aileen Sullivan, Tasha Robinson, Emma Clarkson, Cathy Schulz, Kathy Harris, Wendy Orem, Robin Woolsey, Sarah Archbold and Kris Connolly.

Carol DMR:

We had these rules, like you can’t throw the first punch, one-on-one only. And to be in DMR you had to get in at least one fight.

We had these rules, like you can’t throw the first punch, one-on-one only. And to be in DMR you had to get in at least one fight.

Rachel DMR:

We were some fuckin’ psycho-assed bitches! We didn’t always follow our own rules.

We were some fuckin’ psycho-assed bitches! We didn’t always follow our own rules.

Rachel Rudnick:

Rachel had a mohawk, Toni had the catwoman, which was a double mohawk that had bangs in the middle. Natasha had the skater bangs and the flannel and carried a skateboard and talked shit.

Rachel had a mohawk, Toni had the catwoman, which was a double mohawk that had bangs in the middle. Natasha had the skater bangs and the flannel and carried a skateboard and talked shit.

Sham Saenz:

Carol used to wear black eyeliner that dripped down her face. She was half black and half Jewish. I didn’t even know what a Jew was until I met Carol. She had a little red afro and a Star of David bleached into the back of her head.

Carol used to wear black eyeliner that dripped down her face. She was half black and half Jewish. I didn’t even know what a Jew was until I met Carol. She had a little red afro and a Star of David bleached into the back of her head.

Anna Brown:

She once kicked someone’s ass while she had a peace sign shaved in her head. She was nice to me for some reason.

She once kicked someone’s ass while she had a peace sign shaved in her head. She was nice to me for some reason.

Paul Casteel:

They were little fashion fascists. If there was some new girl in the scene that they didn’t know who was dressed a little bit too preppy, they would try to scare her off.

They were little fashion fascists. If there was some new girl in the scene that they didn’t know who was dressed a little bit too preppy, they would try to scare her off.

Dean Washington:

These chicks from Orinda were

smokin’

. But the DMR was not gonna be okay with those girls.

These chicks from Orinda were

smokin’

. But the DMR was not gonna be okay with those girls.

Carol DMR:

Skimey hoes and sketchy wenches! If you were dressed like a sketchy wench or a hoochie, if you were wearing a short-short skirt and fishnet stockings at the show, you were basically making women look more objectified. We always wore pants and our jean vest, flannel shirts and sometimes a bandana. We just tried to look like cool people instead of what we considered slutty girls. So as soon as we saw somebody like that—we didn’t just start fuckin’ with them—but it was a lot easier when they did something wrong.

Skimey hoes and sketchy wenches! If you were dressed like a sketchy wench or a hoochie, if you were wearing a short-short skirt and fishnet stockings at the show, you were basically making women look more objectified. We always wore pants and our jean vest, flannel shirts and sometimes a bandana. We just tried to look like cool people instead of what we considered slutty girls. So as soon as we saw somebody like that—we didn’t just start fuckin’ with them—but it was a lot easier when they did something wrong.

Other books

janet maple 05 - it doesnt pay to be bad by astor, marie

Bush League: New Adult Sports Romance by Pfeiffer Jayst

House of Ashes by Monique Roffey

Legacy by Alan Judd

Fatal Vows by Joseph Hosey

The Yellow Feather Mystery by Franklin W. Dixon

Somebody's Wife: The Jackson Brothers, Book 3 by Skully, Jennifer, Haynes, Jasmine

Billionaire Bad Boy's Fake Bride: BWWM Romance by Mia Caldwell

Too Wicked to Love by Debra Mullins

The Duke Conspiracy by Astraea Press