Gilded Lily (24 page)

Authors: Isabel Vincent

As the air-kisses flew on that muggy night in August and the Safras greeted everyone from Karl Lagerfeld to Barbara Walters and Betsy Bloomingdale, Lily was living her dream as the grand society hostess of the world's glitterati and movers and shakers. Here was Felix Rohatyn, an investment banker who had restructured New York City's debt in the 1970s and resolved a huge fiscal crisis, arriving with his wife Elizabeth and stepdaughter, the New York socialite Nina Griscom. Across the lawn stood the brooding Christina Onassis, heiress to one of the most fabled fortunes in Europe. Like Lily, Christina had married four times, and had recently broken up with her fourth husband, Thierry Roussel, the father of her only daughter, Athina. As it turned out, Lily's fabulous party was one of the last social events she would attend, for three months later Christina would be found dead of an apparent drug overdose at a country club in Buenos Aires.

If they believed in omensâand Edmond certainly didâmaybe the Onassis death might have given the Safras a few moments of pause. Were they not tempting the evil eye with such a grandiose celebrationâso monumental, so costly, and so

public

!

But 1988 had dawned with such hope. After years of sleepless nights and the agony over his ill-fated decision to sell TDB to American Express, they were back on the society track, attending openings, galas, and fundraisers around the world. Edmond was rebuilding what would turn into a stronger, more lucrative empire on the ashes of a costly mistake; he was reclaiming his most valued employees from TDB and he had started a new bank. He was also building a good case against his former employerâa case he knew he would eventually win. So after the parties, and after a few business meetings with old Halabim clients he had invited to La Leopolda, Edmond looked forward to a few days off in his palatial new home with Lily's six grandchildren.

But their newfound happiness and relief were extremely short-lived.

Â

THE ARGUMENT THAT

escalated into a screaming match between Claudio and Evelyne on the morning of Friday, February 17, 1989, had actually begun at their house on the Gavea mountain in Rio de Janeiro the night before. As usual, Claudio had had a particularly grueling day at work. Simon Alouan, a former professor of mathematics from Beirut who had been appointed by Edmond to head up Alfredo's old company in 1973, was not known for his manners. He could be rough and obnoxious at times, and he was generally feared by everyone in upper management at the appliance chain. Everybody knew that Alouan hated Claudioâhated him with a passion. After all, Claudio was everything he was notâa well-educated, well-mannered member of the Brazilian elite, and certainly a mama's boy, who had been parachuted into his job as head of marketing because

of his mother's influence at the company. Although Lily, as majority shareholder, was technically Alouan's boss, Alouan openly despised her as well. When it came to discussing business matters and the future of the company, he spoke only to Edmond, a fellow Halabim and his most important benefactor. It was Edmond who had brought Alouan to São Paulo to help run one of the Safra family's investment houses in the early days. Alouan, who hailed from an impoverished Halabim family, was eternally grateful to Edmond, who had financed his education in Lebanon.

“Edmond brought Alouan to Brazil and gave him something like 20 percent of the Ponto Frio business,” recalled Albert Nasser. “He always reported to Edmond and refused to take Lily seriously. Every time that she said she was coming to Rio, Alouan would make sure he was on a plane to Europe. With Claudio, he used to put him down all the time and let everyone at the company know that he was good for nothing.”

Claudio's friend Guilherme Castello Branco also recalled the disputes between Claudio and Alouan at the company. “Alouan was very rough, and it was clear that he really despised Claudio,” he said.

Usually by the end of a workday at Ponto Frio Claudio was a nervous wreck. He yelled at Evelyne over the slightest problem and lost his temper with his two young sonsâfour-year-old Raphael and fifteen-month-old Gabriel. He was looking forward to taking a few days off on this summer long weekend and was glad that they had decided to go with their friends Rubem and Ana Maria Andreazza to their summerhouse in Angra dos Reis.

On that muggy Friday morning, as the nanny and the housekeeper readied the children for the two-and-a-half-hour drive to Angra, a beach town southwest of Rio where the coastline is dotted with hundreds of small islands, Claudio and Evelyne picked up their argument of the night before.

“Evelyne was truly an annoying person,” said one of the couple's friends. “Claudio, who was a wonderful person, was a henpecked

husband. After Claudio married her, a lot of his friends stopped going to the house in Gavea. They were always at each other's throats.”

The fight got so ugly that Claudio suggested they drive to Angra in separate cars. He stormed out of the house with Raphael, who had begged Claudio to take him in the car with him. Claudio and Raphael piled into his jeep, a Brazilian-made Chevrolet, to pick up his friend Rubem. Raphael, who loved Rubem, wanted to sit in the front with his father and his friend. Claudio reached in the back to pick up his son and placed him gently between the two adult passengers. Evelyne, Ana Maria, and little Gabriel would drive ahead in a Ford Galaxy Ltd Landau, with Mario, the couple's chauffeur. They would all meet in Angra in a few hours.

Claudio drove fast, past the mansions and grand apartment blocks of the chic beachfront neighborhoods of Leblon and Ipanema, past the crowded favelas, or shantytowns, that cling to the mountainsides, and onto the potholed highway that was the only road to Angra dos Reis. Deep in conversation with Rubem, Claudio probably didn't even notice the

policia militar

truck as it barreled into his lane on kilometer 17 of the Rio-Santos Highway near Itaguai, an impoverished municipality of half-finished brick and plywood houses that marks the halfway point from Rio de Janeiro to Angra dos Reis.

Like Claudio, the driver of the police truck was going far too fast after negotiating a particularly difficult curve. Witnesses said the truck literally passed over the jeep, leaving it a mangled mess of metal.

All three passengers in Claudio's car were killed almost instantly; the impact crushed the Chevrolet, which erupted in flames, and ripped human limbs from their sockets. Claudio's body was unrecognizable when a fire crew pulled him from the wreck. Body parts were strewn on the highway along with pieces of smoldering, twisted metal.

Barely an hour after Evelyne and Ana Maria pulled into the summerhouse they started to worry about the jeep. Later, when a carload of their friends arrived, shaking their heads at the terrible accident

they had just passed on the road, Evelyne feared the worst. Trembling, she demanded a description of the mangled vehicle that police and firefighters were trying to tow to the side of the road to relieve the snarling traffic of weekend travelers that the accident had caused. When her friends described the car, Evelyne drove back along the Rio-Santos Highway. Before she even saw the mangled vehicle, she saw the body parts strewn along the asphalt. When she recognized her little boy's T-shirt, Evelyne started to scream. She never forgave herself for allowing little Raphael to travel with his father. Before the accident, he had always driven with her.

The news of the accident was the lead item on TV Globo's

Jornal Nacional

nightly news program that evening, largely because Claudio's friend Rubem Andreazza was the son of the former minister of the interior in Brazil's last military government, which had ended four years earlier. In Sunday's

O Globo

, the paid obituaries took up nearly two broadsheet pages. Ponto Frio communicated their “profound sadness at the sudden death of our dear director Claudio Cohen and his son Raphael.” The Bloch, Sigelmann, Cohen, and Safra families noted their “great sorrow.” But the saddest announcement came from the grieving mother and widow, Evelyne. It was addressed to Fayale and Cloclo, the names that fifteen-month-old Gabriel used for his older brother and father, respectively: “We will love you always.”

The funeral was on Sunday because Jews cannot be buried on the Sabbath. The extra day also allowed Edmond and Lily enough time to make the trip to Rio from Geneva, where Edmond was plotting his strategy against American Express. Edmond wept openly when he received the phone call from Rio informing him of the accident; Lily was inconsolable.

The burials of Claudio and Raphael occurred just before noon in Rio's high summer, and the air at the Jewish cemetery in Caju, on a bleak stretch of Avenida Brasil in the city's gritty suburbs, was thick and muggy. The mourners sweated in their suits and watched helplessly as Evelyne threw herself sobbing onto the coffin of Raphael,

who was four years and four months old when he died. The impact had fractured his skull. The cause of death, according to the autopsy, was an internal hemorrhage. Claudio, who was thirty-five years old at the time of death, died of a similar injuryâthe sudden impact dislocated and fractured his cranium. He also suffered massive internal bleeding.

Among the group of dark-suited mourners was Claudio's boss, Simon Alouan. But he only made it to the gates of the cemetery to pay his respects to the family before he was ordered to leave by Claudio's sister, Adriana.

“I want to know why you are here!” she screamed hysterically. “You killed him. You're the cause of this. Please, just leave right now.”

Adriana echoed what Lily was also feeling. If Alouan hadn't been such a tough taskmaster, if he hadn't berated Claudio the way he had, perhaps Claudio would not have been under so much stress, perhaps he wouldn't have argued with his wife before getting into his jeep, Lily reasoned. Desperate to lay blame for the death of her beloved son and grandson, Lily also struck out at Alouan. But if she raged against him, she did so quietly. Perhaps she even suggested to Edmond that Alouan could be replaced. The problem with Alouan was that he was doing a good job. Not since Alfredo's day had the company seen such good returns. No, Alouan would stay, ordered Edmond. Lily would have to wait for the best time to strike. It would take fourteen years, but in the end Lily would get her revenge against the man she accused of killing her son.

Although the Cohen and Safra families were devastated by Claudio's death, it was Alfredo's son, Carlos, who went into a deep mourning after the death of his stepbrother. Since their years together at the Millfield School, where Carlos was sent at nine years old immediately following the death of Alfredo, Claudio had embraced the younger Carlos as his little brother. “I was so comfortable with him,” said Carlos. “He was an extraordinary person.”

Â

Â

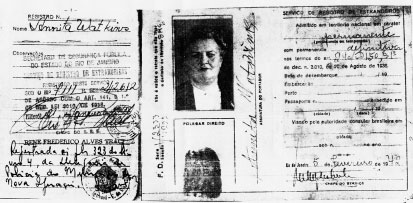

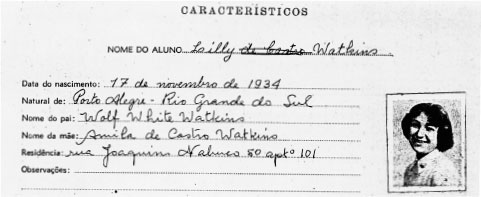

Lily Watkins as a teenager in her school picture. Her birth date is erroneously noted as November 17, 1934.

(Courtesy of Colegio Anglo-Americano, Rio de Janeiro)

Â

Â

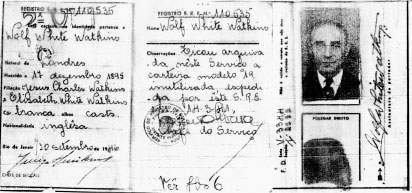

Wolf White Watkins, Lily's father, from his Brazilian identification papers, 1946.

(National Archives, Rio de Janeiro)

Â

Â