Ghost Force (14 page)

Authors: Patrick Robinson

Flying at 30,000 feet, the bomber took thirty-five minutes to come in sight of the jagged coastline of the Passage Islands, fifty miles ahead, guarding the western approach to West Falkland. He immediately swerved southeast, and went almost into a dive, still making six hundred knots.

He made a great sweeping loop keeping his eye on the coastline of East Falkland on his port side. Now, coming in low-level, out of the southeast, right above the waves and below the radar horizon, he “popped up” as he swung around the coastline, ripping through the radar, and taking a bearing on his target before diving back down.

Flying fast over open water, heading northwest, he flashed on his

own radar, and spotted his target one and a half miles out. He released two deadly thousand-pound iron bombs, which came flashing across the surface straight into the harbor, where the only resident warship was in clear view. Instantly, he swung away to the southwest, completely undetected by anyone on land.

No one identified the bombs as they came hurtling at high speed across the water. The first anyone knew of it was when HMS

Leeds Castle

, moored alongside the jetty at Mare Harbor, exploded in a fireball at exactly 0755 on that bright, clear Sunday morning.

Actually, they did not know anything about it even then. A few Royal Navy personnel knew the ship had exploded, but they had no idea how or why. Almost everyone in the little HQ at Mare Harbor was asleep. Twenty-three others, who had been on board the ship, were dead. All of them had been instantly incinerated when the half-ton iron bombs had slammed into the hull and upperworks on the starboard side and detonated with savage force.

The blast tore the heart out of the ship, obliterated the engine room and the ops room, which is located midships, below the upperworks and the big radar mast.

HMS

Leeds Castle

was essentially for scrap. As warships go, she was very small, only 265 feet long, and the wallop in those big Argentine bombs could have sunk a man-sized destroyer. The few Navy personnel sleeping in the accommodation block were naturally awakened by the blast, and they came charging out onto the jetty, half dressed and absolutely stunned at the sight before them.

This was the only warship they had, and it was ablaze from end to end, a searing hot fire sending flames and black smoke from burning fuel a hundred feet into the air.

Plainly there was nothing that could be done, except to try and evacuate any wounded, but to board the ship would have been suicide. Anyway, no one could possibly have survived that fire. HMS

Leeds Castle

, already listing badly to starboard, was doomed. And the twelve sailors who stood on the jetty accompanied by two Petty Officers and a young Lt. Commander were completely astounded at what appeared to be a gigantic accident.

But this was no accident. The forces of Argentina had been preparing for this moment for almost three months. And the remnants of the

warship’s crew, now struggling to locate firefighting equipment, did not know the half of it.

Just for openers, Admiral Moreno had sent a Lockheed P-3B Orion to track the 4,200-ton British Type-23 guided-missile frigate

St. Albans

as soon as it left for the Caribbean. Right now it was four days out making twenty-five knots, 2,400 miles north of the Falklands, 300 miles off Rio de Janeiro. Irrelevant.

This was a proper military operation, conducted by excellent strategists, commanding officers who had weeks earlier placed their assault crews and selected aircraft crews on immediate notice to deploy. Since mid-December they had all been sealed from the outside world, in carefully guarded camps and buildings—waiting for the highly dangerous British frigate to come and go.

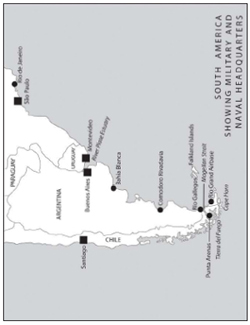

The Argentinian bombers, earmarked for the attack, had been flown down from the parent bases in Rio Gallegos, where the forward tactical command headquarters had been established.

And even as the Royal Navy’s makeshift damage control units finally connected their hoses to quell the fires, two French-built delta-winged Mirage III Es, proudly displaying the livery of the Argentine Air Force, came sweeping out of the skies above the northern coast of East Falkland.

Each armed with 2-X-30mm cannon and two air-to-surface missiles, they flew fast at 20,000 feet, flashing over the settlement of Port San Carlos, which had scarcely echoed to the roar of fighter-bombers for twenty-eight years.

The Mirage jets swerved overland, high above the foothills of the desolate Mount Simon, and screamed over the landlocked end of Teal Inlet, crossing the lower slopes of Wickham Heights. And at that moment, Royal Air Force Sergeant Biff Wakefield picked them up on his Rapier missile radar system, on Mount Pleasant Airfield, twelve miles to the south.

He caught two “paints” moving very fast, and he picked up a French radar transmission, precisely as Oscar Moreno knew he would. Sgt. Wakefield tracked the two “paints” even though he knew they were well beyond the reach of his own missiles.

Outside, beyond his small concrete-built ops room the two big Rapier missile launchers stood at permanent readiness. But there was

no point activating them yet; the two Mirage jets were over Berkeley Sound headed out to sea and off the screens. But Biff Wakefield kept them tracked as well as he could.

What he could not know was the real danger. And that suddenly burst out of the skies north of Falkland Sound, two more Mirage III Es, rocketing over the rocky granite coast, but not on the same easterly course as the other two. This pair was heading southeast.

And before Sgt. Wakefield’s three-man team had even a chance to locate and identify, the Argentinian pilots unleashed two air-to-surface bombs each, all four of them aimed at the big short-range RAF Rapier launchers to the west of Mount Pleasant Airfield.

They came homing in at more than 500 mph, blasting both launchers to smithereens, followed by both Mirage jets, which opened up with their 30mm cannons, riddling the area with shells, smashing through the window of the ops room and killing Sgt. Wakefield and both of his duty operators. Their radar surveillance was still aimed to the northeast in search of Argentina’s fleeing decoys.

In the space of five minutes, Great Britain’s sea defensive unit, HMS

Leeds Castle

, and the entire air defense cover system for Mount Pleasant had ceased to exist. And that was by no means the worst of it.

Ninety minutes before first light, five hundred Marines from Argentina’s Second Battalion had disembarked from landing craft on the deserted coast just west of Fitzroy. They had been marching steadily for a little over two hours, and right now were positioned on a bluff overlooking the airport. They were late, cursing their luck at not making it in the dark, but nonetheless ready for their daylight assault on the British garrison.

Meanwhile, the garrison ops room on the airfield, which had been ignored in the air attack on the Rapier launchers, understood they were under some kind of attack. They could see the flames still leaping skyward from the harbor, and they of course knew they had been slammed by bombs or missiles in the past few minutes.

Captain Peter Merrill ordered his immediate response platoon stood to. They already had their weapons and ammunition to hand, and the duty officer had them deploy instantly, initially to man all prepared positions around the airfield buildings and control tower.

The Captain alerted the Company Commander, Major Bobby

Court, who ordered every man in his 150-strong force to get up, dress, assemble, and draw their weapons from the armory, full scales of ammunition from the stores’ color sergeant. The machine-gun section also drew their weapons, together with spare barrels, and 12,000 rounds of boxed ammunition packed into belts of 250.

Twenty minutes later, with everything and everyone loaded onto Army trucks, they began to move out of the garrison toward the airport buildings. And as they did so, they heard the opening bursts of gunfire erupt from the bluff to the west, as the Argentinian Marines began to rain down fire on the vehicles of the British immediate-response platoon.

Led by Lieutenant Derek Mitchell, they poured out of the trucks and went to ground, desperately trying to locate where the small-arms fire was coming from. They had taken nine casualties in that opening burst and the stretcher parties were not yet assembled.

It took five minutes to identify the positions of the Argentinian Marines, and Lieutenant Mitchell ordered his men to fire at will. The Argentinians could see they were up against a much smaller force, and began to advance.

The British infantry held them as best they could, but the Marines were well commanded by Major Pablo Barry, who split his force, ordering a separate company to move around onto the left flank of Lieutenant Mitchell’s platoon.

That took fifteen minutes, and the moment they were in position, Major Barry ordered the Marines to fix bayonets, spread out in assault formation, and advance. By now Britain’s immediate-response platoon had taken heavy casualties, and was reduced in numbers by approximately half.

Which left around twenty-five British infantrymen to face the oncoming five hundred from all directions, and right now they were still trying to fire at the first company that had engaged them.

With only fifty yards between the troops, the flanking Marine assault party began to close in, opening fire, gunning down the British troops from this unexpected direction. Alternately they used the bayonet to great effect. Overwhelmed by sheer weight of numbers, not one British rifleman survived the battle. Lieutenant Mitchell died from bayonet wounds to his back and lungs. The Argentinians lost only twenty-three Marines.

Meanwhile Major Bobby Court had the rest of his infantry company thundering into position, the big Army vehicles transporting everyone to the airport and its surrounds. They knew things had already gone badly among the immediate-response group, but they still had two heavy machine guns, which they carefully sited on the flanks of their defensive position. They might have been surprised and outnumbered, and they might have been totally unprepared to withstand an assault on this scale, but the Brits were no pushover.

As the Argentine Marines began their second advance toward the airport buildings, Major Court’s machine guns raked the area, the fire interlocking across the front of the company. The invading Argentinian Marines took over fifty casualties on their first assault, retreated, and gave the defenders time to organize a first-aid post and reserve stocks of ammunition.

Again the Argentinians attacked and were once more repulsed. And now they went to their mortars, laying down indirect fire and still trying to penetrate the wall of steel spitting from the British machine guns.

Once more they took many casualties, out there on that exposed ground, but they kept coming, using smoke bombs to disguise their advance, running forward, hurling grenades close in to the trenches, all under the cover of a barrage of mortars.

And, as before, they eventually overwhelmed the defenders by weight of numbers. Only seventeen British riflemen survived, eight of them badly wounded.

Major Pablo Barry immediately took charge, and called upon all civilians in the airport buildings to offer no resistance. The wounded were taken into the buildings, where British and Argentine medical staff administered first aid to casualties on both sides.

Major Court was badly injured in the attack and died that evening in the passenger terminal. And before he did so, the last element of British resistance was removed when a Special Forces troop of seventy-five flew in from Rio Gallegos and immediately overwhelmed the small naval garrison at Mare Harbor with one volley of light-machine-gun fire along the jetty. Only two of the seven sailors still on duty were hit, and Lt. Commander Malcolm Farley ordered his men to surrender.

Two hours later the big Argentinian C-130s began landing at Mount Pleasant, carrying troops and light vehicles of the Fourth Air

borne Brigade based at Cordoba. Swiftly organized, they took it upon themselves to haul down every British flag on the airport and replaced them with the light blue and white symbol of the Republic of Argentina.

Then they turned north and drove into Port Stanley, using bullhorns to instruct the citizens to stay within their houses. As ordered, they were swift and brutal to any objections to their presence, clubbing down five islanders with rifle butts and booting in the doors of houses that seemed likely to shelter armed civilians.

At 1800, they ordered the Governor out of his residence and drove him and his family and staff to the airfield, shipping them out immediately by air, to Rio Gallegos.

At fifteen minutes past six o’clock, on Sunday evening, February 13, 2011, the Argentinian flag flew over Port Stanley for the first time since June 1982, when Britain’s Second Battalion Parachute Regiment had ripped it down and replaced in once more with the Union Flag of Great Britain. It was ten o’clock in the evening in London.

The most astonishing aspect of the lightning-fast Argentinian military action on that Sunday in mid-February was the failure of the British land forces to make any form of communication with their High Command. The same applied to the survivors in the Royal Navy garrison.

Under normal circumstances one would have expected Lt. Commander Malcolm Farley to have instantly contacted the closest Naval Operations base. The problem was, Lt. Commander Farley had a 1,400-ton warship on fire right outside his front door, with many dead and some wounded. The nearest help was all of 2,400 miles away—the north-heading frigate—and his home base was 8,000 miles away in Portsmouth.

The problem for Major Bobby Court was much the same. There had been a ferocious attack on the missile system that protected the airport, his men were under serious small-arms fire, and generally speaking everyone was just trying to stay alive. The nearest help was thousands of miles away, and they were all in a life-or-death fight with the Argentinians.

Neither Lt. Commander Farley nor Major Court lived to make the communication, and it was not made by anyone until six p.m. (local) on a telephone in the passenger terminal at Mount Pleasant Airfield.

Sergeant Alan Peattie, who had manned one of the heavy machine guns, and somehow emerged unscathed, called the British Army HQ in Wilton, near Salisbury, where the duty officer, stunned by what he heard, hit the encrypted line to the Ministry of Defense.

That represented another duty officer absolutely stunned, and he in turn called Britain’s Defense Minister at his home in Kent.

At 10:24 p.m. the telephone rang in the British Prime Minister’s country retreat, the great Elizabethan mansion Chequers, situated deep in the Chiltern Hills, in Buckinghamshire to the west of London. The Defense Minister, the urbane former university lecturer Peter Caulfield, personally relayed the daunting news.

The Prime Minister’s private secretary took the call and relayed the communiqué:

Argentinian troops have invaded the Falkland Islands. The British garrison fell shortly before ten p.m. GMT. Port Stanley occupied by Argentinian Marines. HMS

Leeds Castle

destroyed. Governor Manton under arrest. The national flag of Argentina flies over the islands.

The color drained from the PM’s face. He actually thought he might throw up. Twice in the previous month he had been alerted to the obvious unrest in Buenos Aires. He had been informed by his own Ambassador of the shouted words of the Argentinian President from the palace balcony on New Year’s Eve.

There had even been reports from the military attaché in Buenos Aires of troop movements, and more important, aircraft movement at the Argentinian bases in the south of the country. He also recalled ignoring reports of Argentinian anger at the oil situation on East Falkland.

He had three times spoken to the Foreign Minister in Cabinet, mildly inquiring whether there was any need to sit up and take notice. Each time he had been told, “We’ve been listening to this stuff for over twenty years. Yes, the Argentinians are less than happy. But they’ve been less than happy for the biggest part of one hundred eighty years. In point of fact we’ve had exceptionally agreeable relations with Buenos Aires for a very long time. They won’t make a move. They wouldn’t want another humiliation.”

The Prime Minister had accepted that. But the decisions in the end were his, and so was the glory, and so was the blame. And this was a Prime Minister who was allergic to blame, at least if it was pointed at him.

He excused himself from the crowded dinner table and walked with

his secretary through the central hall, past the huge log fire that permeated this historic place with the faint smell of wood smoke in every room. He entered his study and picked up the telephone, greeting the Minister of Defense curtly.

“Prime Minster,” said the voice on the other end. “Not to put too fine a point on it, Argentina just conquered the Falkland Islands. Our troops defended as well as they could, but we have at least one hundred fifty dead, and HMS

Leeds Castle

is still on fire, with her keel resting on the bottom of Mare Harbor.”

“God almighty,” said the PM, his thoughts flashing, as they always did in moments of crisis, on to the front pages of tomorrow’s newspapers, not to mention tonight’s television news.

“I’m sure you realize, sir,” continued the Minister, “we have no adequate military response for thousands of miles. I regret to say you are in an identical situation to Margaret Thatcher in 1982. We either negotiate a truce, with some kind of sharing of authority, or we go to war. I firmly recommend the former.”

“But what about the media?” he replied. “They’ll instantly compare me with Margaret Thatcher. They’ll find out about the warnings we received from Buenos Aires, then blame me, and to a lesser extent you, for ignoring them. The Foreign Secretary will have to resign, as Mrs. Thatcher’s did. And then they’ll ask what we’re made of.”

“Prime Minister, I do of course understand your concerns. But right now we have one hundred fifty dead British soldiers, sailors, and airmen on East Falkland. Arrangements have to be made. Someone has to speak to the President of Argentina. I am happy to open the talks—but I think you are going to have to speak to him personally.

“Meanwhile, I think the Foreign Office should start by making the strongest possible protest to the United Nations. I’m suggesting an emergency Cabinet meeting in Downing Street tonight, perhaps attended by the military Chiefs of Staff.”

“But what about the media?” repeated the Prime Minister. “Can we stall them? Can we somehow slow it all down? Call in the press officers and our political advisers? See how best to handle it?”

“It’s a bit late for that, Prime Minister. The Argentinians will have the full story on the news wires, probably as I speak—

Heroic forces of Argentina recapture the Malvinas—British defeated after fierce fight

ing—the flag of Argentina flies at last over the islands…Viva las Malvinas!!

We can’t stop that.”

“Will the press blame me?”

“Undoubtedly, sir. I am afraid they will.”

“Will it bring down my government?”

“The Falklands nearly brought down Mrs. Thatcher. Except she instantly went to war, with the cheers of the damned populace ringing in her ears, and the military loved her.”

“They don’t love me.”

“No, sir. Nor me.”

“Downing Street. Midnight, then.”

“I’ll see you there, sir.”

The British Prime Minister walked back across the central hall of Chequers with a chill in his heart. He was not the first PM to feel that emotion since first Lord Lee of Fareham gifted the great house to the nation in 1917, during the premiership of David Lloyd George.

And he probably would not be the last. But this was a situation in which there was no room for maneuver. And it was a situation that would require him to address the nation, immediately after the Cabinet meeting. He knew instinctively the press would give him a very, very rough ride…

Surely, Prime Minister, you were aware of the unrest in Buenos Aires…? Surely, you must have been told by your diplomatic advisers that all was not well in the South Atlantic…? Stuff like this never happens without considerable preparation by the aggressors…surely someone must have known something was going on?

But the one he really dreaded was…

Prime Minister, you and your government have spent years making heavy cuts to the defense budget, especially to the Navy…do you now regret that?

He would take no questions at that first announcement, that was for certain. He needed time to think, time to confer with his media advisers (spin doctors), time to arrange his party line, time to deflect the blame onto either Whitehall or the military. But time. He must buy himself some time.

Meanwhile, he must not display panic. He must return to his guests. And he thanked God he had not invited anyone for this Sunday night dinner who was connected in any way with the military.

Seated around the table were the kind of people a modern progressive Britain admired. There was one hugely successful homosexual pop singer, Honeyford Jones, who was reputed to be a billionaire. There was the international football striker Freddie Leeson and his gorgeous wife, Madelle, who once worked in a nightclub. There was the aging film star Darien Farr and his wife, Loretta, a former television weather forecaster. Plus the celebrity London restaurateur Freddie Ivanov Windsor, who sported a somewhat unusual name for an English lout.

These were the kinds of high achievers a contemporary Prime Minister needed around him, real people, successful in the modern world. Not those dreadful old establishment politicians, businessmen, diplomats, and military commanders so favored by Margaret Thatcher.

These were people who were proud to be his acquaintances. They were people who hung on his every word, and did not ask a lot of unnecessary questions. And when he sat down he decided to tell them what had happened.

“I’m afraid our armed forces have had a bit of a setback in the South Atlantic,” he said gravely. “The Argentinians have just attacked the Falkland Islands.”

“Where’s that?” said Loretta.

“Oh, it’s in the South Atlantic—just a tiny British protectorate going way back to the nineteenth century,” he replied. “Of course we knew there was a lot of unrest in the area, but I don’t think my Foreign Office realized quite how volatile the situation was.”

“Jesus. I remember the last time that happened,” said Darien. “I was in my, like, dressing room on the set…and they announced on the television we’d been attacked…I was…you know…like, wow!”

“Oh, that must have been, like, awful for you…in the middle of a movie and everything,” said Madelle.

“Well, we all knew it was very uncool,” he replied. “You know, like really, really bad, getting attacked by a South American country…but I mean everyone was totally, like, wow!”

“So what’s it with these fuckin’ Argeneeros then?” asked Freddie. “I mean, what are they on about? First up, they got a bloody big country, ain’t they? Second, do I look as if I care there’s a war or whatever in the Falktons, I mean, like who gives?”

The Prime Minister, for the first time in his premiership, suddenly

wished he had chosen different friends for tonight’s dinner. He stood up and said, “I’m sorry. But I’m sure you all understand I have to return to London.”

Everyone nodded, and Loretta called out, “Get on your mobile, babe. The Army will get down there. Best in the world, right? Sort them Argeneeros out, no pressure.”

The PM shuddered as he made his way back across the central hall to the government limousine waiting outside. He had staff to sort out the details of his return to Downing Street. He just climbed in the rear seat of the Jaguar and sighed the sigh of the deeply troubled.

Like all Prime Ministers, he loved the grandeur of this seven-hundred-acre country retreat. And he was aware of the immense decisions that had been reached down the years within its walls. He also knew, and the knowledge caused his soul a slight quiver, that Margaret Thatcher had sat in her study at Chequers to compose her perfectly brilliant personal account of the mighty British victory in the Falklands nearly thirty years ago.

He was assailed by doubts, the kind of doubts that cascade in upon a self-seeking career politician who does not possess the guiding light of goodness and purpose that always gripped Margaret Thatcher. Gloomily, he doubted his manhood, and he gazed out at the Chequers estate, which was frosty in the pale moonlit night.

He truly did not know if he would pass this way again, given the Brits’ unnerving habit of unloading a Prime Minister before you can say knife. Out of Downing Street in under twenty-four hours; glorious weekends at Chequers…well…those became instant history. Pack your stuff and make a fast exit.

Traffic returning to London was light, and the PM had only an hour or so to ruminate on his recent exchange with Sir Jock Ferguson, the Chairman of the hugely influential Joint Intelligence Committee. In two very private phone calls, Sir Jock had tipped him off there was trouble brewing in Buenos Aires over the Falkland Islands.

This had been precisely the news no government wanted to hear with a general election coming up in less than seven months. No PM wants to be seen to take his nation to war, and then ask for everyone’s vote. Even Winston Churchill was unable to pull that one off after World War II in 1945.