Ghost Dance (36 page)

Lieutenant Bowman had found Mary Horses’ bones in a bag in the trunk of Monsignor McColl’s car, hidden in the woods near the base of Gorm Ridge. The bones were coated with soil that matched dirt in the hole in the rectory garden. Father D’Angelo had buried her beneath the birdbath and watched over her relics for the last twenty years of his life.

Gallagher had decided that whether or not Father D’Angelo got his power to heal from those bones was an unanswerable question. Certainly Monsignor McColl believed that Many Horses’ bones were like the bones of saints, still imbued with the power of an infinitely generous soul and therefore capable of providing healing and forgiveness.

In the months immediately following the carnage on Lawton Mountain, people who had grown up in the various orphanages and parishes McColl had overseen came forward out of the shadows to testify about his abuse and the psychological terror he had used to control them.

The entire story of Mayor Powell’s family’s involvement in the killing of Many Horses came out, too. And that opened up a flood of stories about other crimes the family had covered up over the years, including Chief Kerris’ assault on Andie twenty years before. In March, Mayor Powell was indicted on charges of accepting a kickback from the New Jersey developer who wanted to build the hotel-and-condominium complex at the ski area on Lawton Mountain.

But Gallagher’s coming to some kind of closure as far as Terrance Danby was concerned proved a more difficult assignment. He spent a great deal of time in the year trying to learn more about Harold and his relationship to Danby. But he had little success tracking the man and had been officially discouraged from doing so on several occasions. Gallagher had come to think of Harold as one of those oracular creatures whom heroes are destined to encounter during their journey through hell.

Using his partner’s other contacts, however, Gallagher had been able to put together the barest skeleton of Terrance Danby’s life between the time he left Harold’s employment and the killing of Hank Potter.

Danby worked as a freelance assassin all over Central and South America. During a party in Caracas four years before, he met Angel Abatido, the stunningly beautiful daughter of a right-wing colonel in the El Salvadoran army.

Three months before the killings in Lawton began, a cleaning lady entered Abatido’s apartment in a swank section of San Salvador and discovered her body. Angel was naked on the bed, a noose lynched tight about her neck. Police found thirteen different, organic, mind-altering substances in the room with her. There was evidence her killer had lain with her long after death.

Gallagher had come to think of Angel’s murder as the trigger that set Danby off. But he understood better than most that the tortured killing machine Danby became was forged long ago by heated events Danby probably never came close to understanding himself. In his own way, Danby was someone like himself. He had been searching for proof that there was something beyond the ugly existence that had abused him mightily as a child. Despite the vicious amorality of his crimes, Gallagher could not help but see things in Danby to pity.

The shaman’s name was Henry Long Lance. He was an intense, proud man with flowing black hair and the demeanor of a stoic old warrior. But this morning, as the coffin carrying Sarah Many Horses was lowered into the ground above the Grand River, not far from where her uncle Sitting Bull had been murdered and she had begun the long journey to Vermont, where she herself had been slain, Henry Long Lance’s eyes welled with joy.

He carried a feathered eagle staff in one hand and, in the other, a sacred calf pipe purified and remade from the bowl that had belonged to Ten Trees in another life.

He raised the pipe and the eagle staff toward the sky and began to pray.

The crowd had swelled and was perhaps a thousand now, young and old who’d come out from the various Lakota reservations to see her buried.

Andie and Gallagher stood respectfully back from the crowd beside Roger Barrett, the professor from Dartmouth who had spent almost a year helping them arrange to bring Sarah home. In return, they had given him the first look at Many Horses’ journal. Barrett called it a remarkable anthropological discovery, but could not hide his disappointment that Gallagher had inadvertently burned the pages that described her version of the Ghost Dance ceremony.

Long Lance raised the sacred calf pipe and sang in Lakota. Many in the crowd joined in and at every pause between verses they turned to a new direction: from the west, to the north, to the east and finally to the south.

Someone in the crowd blew through an eagle-bone whistle, and the shrill sound carried and bounced and returned from off a far butte. Gallagher could not help thinking about the discussions he’d had with Professor Barrett in the past few months. Most of their talk had centered on whether Sarah could actually talk with the dead; and whether he and Andie had actually crossed to the other side during Danby’s crazed reenactment of the long-lost ritual; or whether they had merely been under the mechanical influence of the hallucinogenic mixture the killer had made them smoke.

Gallagher had looked at it in many ways and had come to believe that the rituals passed down by Ten Trees, Painted Horses, Sitting Bull and Wovoka were real and powerful because someone like Sarah Many Horses had proven faith in them over a lifetime. She believed she could talk with her dead, and Gallagher believed she did, too.

Now Long Lance launched into a prayer in Lakota. Andie wrapped her arms around Gallagher and rested her head against his chest, and he could not help thinking that Emily had been right in ways she could not have imagined the day she left him. She said that to believe in the afterlife, Gallagher had to first believe in this life. That takes a belief in love.

Gallagher hugged Andie close and added his own interpretation of what his ex-wife had been trying to teach him: if you allow another spirit like Sarah Many Horses or Andie Nightingale to come and live with you, they can never die. Nor can you, for acceptance means you have become the vessel of love, the immortal force that transcends life and death.

Gallagher had allowed Many Horses’ story to live within him as it obviously had lived within Father D’Angelo for so many years; and because of it, he had been granted the ability to perform miracles. Gallagher had been given a vision of the afterlife that allowed him not merely to survive but to finally embrace this existence for all its good and menace.

A group of men came forward and lowered Many Horses’ coffin into the grave. They shoveled dirt into the hole as Long Lance began to sing again. As he sang, he scraped a circle on the ground next to the grave. He made a second circle with the dirt taken from the trough of the first, then crafted a cross that ran from west to east and then from north to south.

On the southern tip of the mounds in that second circle, he placed Ten Trees’ pipe and a leather bundle in which he had placed Many Horses’ lock of hair, her stones and a piece of paper on which she had written her journal.

Barrett leaned over and whispered, ‘He’s beginning the rite of releasing the soul.’

Andie and Gallagher held on tighter to each other. Gallagher prayed that she felt the same strength in him that he felt in her. Andie had not had a drink since the night he’d found her passed out with her mother’s piece of the journal. And not once since had she ever expressed a desire for the bottle. She rotated around in his arms, so his belly was to her back. She placed her free hand on her stomach and smiled at him as the ceremony went on in the softly slanted light of a Dakota June afternoon.

Long Lance stopped singing. Then he smoked and passed the pipe among those gathered. A willow post had been set in the ground next to the circles and the grave, and on it was placed a buffalo-skin robe and a piece of buckskin on which a face had been painted. Professor Barrett whispered that the effigy represented Many Horses’ soul. Women carrying bowls of food walked clockwise around the grave, the circles and the post. They hugged the effigy, men set the food before it.

Then four young girls came forward and Long Lance placed a small bit of food in their mouths and had them drink from a bowl that Barrett said held cherry juice.

When they were finished, Long Lance picked up the leather bundle and said, ‘You are about to leave on a great journey. Your father and mother and relatives and many strangers have loved you.’

Then he walked the edge of the circle four times. The first three times he reached the southernmost point of the circle, Long Lance held Many Horses’ bundle up high and cried, ‘Always look back upon your people, that they may walk the sacred path with firm steps.’

Far down on the river bottom, a gust of wind swirled and took pale leaves from the cottonwoods, and they shifted and spiraled upward in the late-afternoon light. Barrett leaned over again to say something, but Gallagher cut him off.

‘I know,’ Gallagher choked. ‘Many Horses is crossing the river.’

‘Not all of her,’ Andie whispered. She pressed Gallagher’s hand to her belly, already swollen for six months. ‘Part of Sarah is right here. Can’t you feel her?’

I

AM DEEPLY INDEBTED

to Linda Chester, my literary agent, wise counsel and friend, and to her ever-energetic associate, Joanna Pulcini. Their constant enthusiasm and support have kept me going through the years.

I am likewise grateful to Ann McKay Thorman, my editor, and Lou Aronica, my publisher, for their patience and advice while this novel took shape.

Thanks also to my friend Damian Slattery, whose critical reactions and good-natured encouragement have made me a better writer; and to my wife, Betsy, who always gets to read first.

I owe a great deal to the following anthropologist and ethnologists: Father Raymond Bucko; Richard (Fire) Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes, authors of

Lame Deer Seeker of Visions;

William S. Lyon, author

of Black Elk: Then and Now,

William K. Powers, author of

Yuwipi: Vision and Experience in Oglala Ritual;

Joseph Epes Brown, recorder and editor of

The Sacred Pipe, Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux,

Renée Sampson Flood, author of

Lost Bird of Wounded Knee;

and Richard E. Jensen, R. Eli Paul and John E. Carter, authors of

Eyewitness at Wounded Knee.

Their works gave me insight into the mind of the shamanic Sioux. Any error in interpretation, however, is mine alone.

I also thank Steve Eddy, Joe Citro and Chris Whelton for sharing their knowledge and research about the nineteenth-century spiritualist activities of the Eddy brothers of Chittenden, Vermont; and thank Bobby Sand for sharing his understanding of the Vermont judicial system.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

copyright © 1999 by Mark T. Sullivan

cover design by Heather Kern

978-1-4532-6878-0

This 2012 edition distributed by MysteriousPress.com/Open Road Integrated Media

180 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

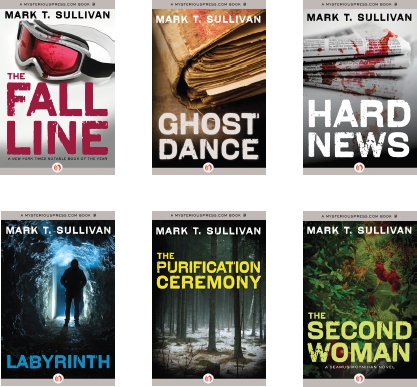

MARK T. SULLIVAN

FROM MYSTERIOUSPRESS.COM

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA