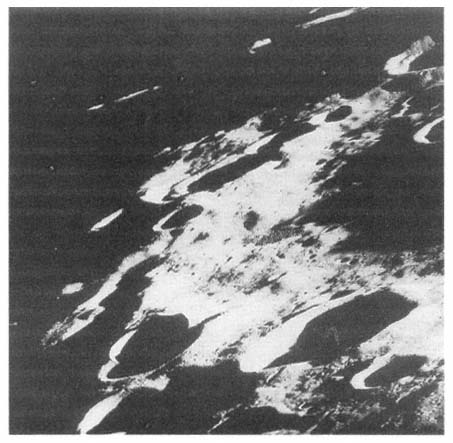

that almost every crater appeared to be of impact origin. He added that a manned landing on the far side of the moon would be difficult. "The backside looks like a sandpile my kids have been playing in for a long time. It's all beat up, no definition. Just a lot of bumps and holes."

|

Periodically Borman would open his eyes and though still half-asleep mumble a question about the time, the ship, the situation. The others would reassure him that all was fine, and he would drift back asleep.

|

At 4 PM, the spacecraft moved behind the moon for the seventh time. Lovell was still at the helm, and humming and singing aloud as he guided the ship through space.* Anders worked the cameras. Neither had slept.

|

Borman, however, was finally up, but he wasn't ready to return to work. He ate, used the "Waste Management System," and joked with the other two men.

|

At one moment Lovell looked out the window, and then at his crewmates. "Well, did you guys ever think that one Christmas you'd be orbiting the moon?"

|

Anders quipped, "Just hope we're not doing it on New Year's."

|

Lovell, who was usually the joker, didn't find this funny. "Hey, hey, don't talk like that, Bill. Think positive."

|

Two hundred forty thousand miles away, Marilyn Lovell decided she needed to go to church. She had spent the day of Christmas Eve at home with friends, trying to fill the time as the spacecraft orbited the moon. Periodically she wandered back to her bedroom for some quiet. Other times she listened to the squawk box. And she smoked a lot.

|

Finally, by late afternoon the magnitude of the day's events were wearing on her. She wanted to pray, but she wanted to do it alone. She called Father Raish at St. John's to ask him if she could come to church, and he told her to come right over.

|

|  | * Lovell sang aloud repeatedly throughout the mission. Neither he, Borman, nor Anders remember the tunes, however, and the transcripts do not say, stating merely that he was (singing)."

|

|