next fourteen days. You cannot leave to go to the bathroom, to eat, or to shower. Imagine that you have radio headsets on and that every word you say is being recorded by an army of doctors. Imagine also that those doctors have attached sensors to numerous places on your body. They have many different questions to ask you, and you have no choice but to try to answer them.

|

Imagine as well that the car's air conditioning doesn't work very well, the car is sitting in the hot sun, and you have to wear a heavy, insulated jumpsuit. The temperature rises and there is nothing you can do.

|

And finally, imagine that though the car's engine is in gear and running and the car is in motion, the steering column is turned all the way to the right, and for the entire two weeks you continually go around in circles, watching the same scenery go by again and again and again, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

|

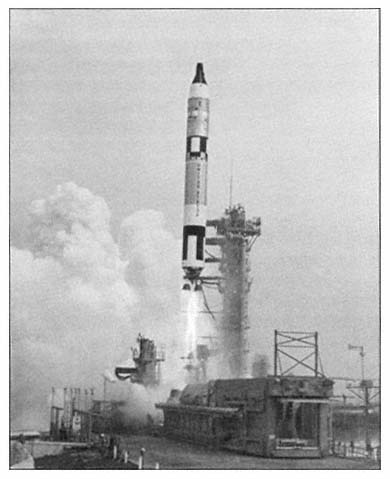

This is the experience that began for Frank Borman and Jim Lovell on December 4, 1965 at 1:30 PM (C.S.T.). At that moment they lay on their backs on top of a one-hundred-twenty-foot-tall raging behemoth. The Titan rocket on which their Gemini capsule sat had just ignited, and though it was only a third as tall as the Saturn 5, it was a significantly rougher ride. Spewing out 430,000 pounds of thrust, twice as much as a Boeing 747 at takeoff, the Titan felt like a bucking bull at a rodeo.

9

|

It was the first space flight for both men, and in as many ways as possible Gemini 7 illustrated the unpleasant and miserable side to human exploration. Their mission was to prove that a human being could survive fourteen days in space, and for two weeks they went around and around and around and around the earth, completing two hundred six orbits and seeing as many sunrises and sunsets.

|

For the first two days of Gemini 7, the rules required that Borman and Lovell stay in their spacesuits, which they found hot and uncomfortable. After that, if one astronaut was in shirtsleeves, the other had to be in his suit. The original plan called for them to switch places each day, with Jim Lovell in his longjohns on the third day, and Frank Borman out of the suit on the fourth, and so on.

10

As it turned out, Lovell asked if he could stay unsuited on the second night, and Commander Borman made the decision that since his crewmate was a larger man and had greater difficulty getting out of the

|

|