Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash (7 page)

Read Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair With Trash Online

Authors: Edward Humes

Tags: #Travel, #General, #Technology & Engineering, #Environmental, #Waste Management, #Social Science, #Sociology

Emits polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which can be highly toxic, have been linked to cancer and can cause birth defects or fetal death.

Twenty families burning trash in their backyard put out more cancer-causing dioxins than a modern industrial facility that burns the trash of 150,000 families.

In 1987, industry accounted for about four-fifths of total dioxin emissions in the U.S. By 2010, dioxin emissions were reduced by a factor of thirteen because of industrial pollution controls. But of the dioxin emissions that remained, home trash burning was responsible for nearly two-thirds of them.

But when it came to the three hundred thousand to half million backyard incinerators in Los Angeles, the so-called Smokey Joes, and the estimated 500 tons of sooty, toxic air pollutants they churned out each day, the story was different. People simply did not want to give them up.

F

OR DECADES,

Angelenos had been encouraged and expected to incinerate their trash. It wasn’t just convenient, they had been told, it was a civic duty, a way of avoiding costly trash collection services, taxes and bills. They did not want to give up their burn barrels and piles of smoking rubbish, and they let their elected officials know it. The thinking was that a bit of soot and smoke in the backyard couldn’t possibly be as big a problem as massive refineries, factories and freeways full of cars. Besides, where would all the trash go? What would it cost? Who would pay? Public sentiment clearly tilted in favor of letting officials address the perceived bigger smog culprits first, the smokestacks and the tailpipes, while leaving those deceptively small backyard burners alone. And so the incinerators would not go gently.

Neither did the million filthy, soot-covered smudge pots that orange growers and other farmers employed to protect crops from freezing overnight, burning old crankcase oil, discarded tires—anything cheap and combustible, which always meant dirty and toxic. It took years to convince them to switch to cleaner devices and fuels, due to the prevailing and utterly false belief that the smoke “helped hold the heat” close to the ground. Incinerator manufacturers fought back to protect their interests, too, at one point trying to make their products appear more cuddly by marketing sheet metal incinerators shaped like little houses and featuring smiling faces painted beneath stovepipe chimney “hats.”

It took seven years of failed attempts to finally pass the ordinances to ban incinerators countywide in 1957. The smog had grown so bad by then that it became nearly impossible to dry clothes successfully on outdoor laundry lines without them absorbing a rain of black soot. Complaints about the dirty byproducts of backyard burning finally matched the defenders, and politicians felt sufficiently safe to act: no more burn barrels, no more happy-face incinerators. Jail and a five-hundred-dollar fine awaited illicit burners, and Smokey Joe was finally toast.

As predicted, the home incinerator ban led to greater volumes of trash in need of disposal, which meant new trash hauling services by both government and industry arose to meet that need. And the garbage had to go somewhere once it was picked up, too. A web of dumps ringing the basin soon opened to accommodate the new and rapidly growing river of trash—growing because Los Angeles was growing, with bean fields and orange groves converted on a daily basis to postwar, GI-Bill-financed suburban housing tracts. Along with the real estate boom, trash became a growth business as never before.

One place in particular drew Los Angeles’s new mounds of garbage—the area surrounding the eastern L.A. County foothills bordering the San Gabriel Valley. Strategically located in an area with ample open land, it straddled a confluence of major highways and lay near several populous communities—the ideal mix of convenience and seclusion for trash disposal. There was not a single large repository for garbage opened then, but a profusion of small, privately owned garbage destinations. They were open dumps, like the vast majority in America at the time, where refuse was tossed and piled and, in many locations, burned. In short order this area of L.A. bore a nickname worthy of Fitzgerald: the Valley of the Dumps.

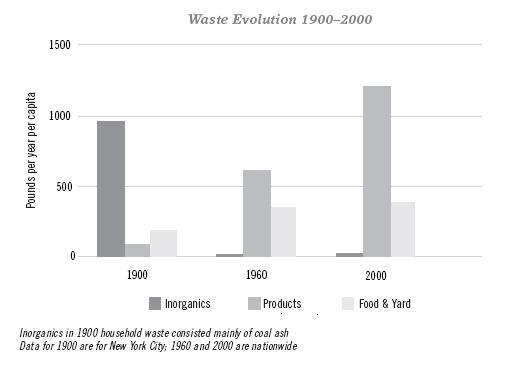

Demand for dump space began mounting then, not only in Los Angeles, but also nationwide. Bans on incinerator and backyard burn piles were only part of the reason. Another trash multiplier had arrived right around the same time: the rise of America’s new consumer culture and the disposable economy ushered in with it. A new tidal wave of trash began to crest then, combining the old refuse that once had been burned with a new flow of disposable trash, containers and short-lived products never before seen. Consumption and garbage became more firmly linked than at any other time in history, with the disposal of products and their packaging displacing other categories of household waste for the first time in our trash history. That trend hasn’t changed since 1960.

The age of the plastic bag was upon us.

3

FROM TRASH TV TO LANDFILL RODEOS

N

OW AND THEN WHEN THE WIND BLOWS JUST RIGHT

and the day’s garbage is still baking uncovered in the Southern California sun, a flock of strange birds can be seen wheeling above the Puente Hills landfill. Upon closer inspection, however, some of these fliers turn out not to be birds, but escaped plastic grocery bags, which are woven like veins throughout every load of trash dumped in every city landfill in America. Sometimes a few break free of the piles of dirty napkins, spent kitty litter and broken glass holding them down, and they scuttle like urban tumbleweeds across the jagged top of the trash cell, then take flight. This is one of the myriad ways plastic trash makes its way into streets and rivers and oceans, and demonstrates the drawback of engineering products with useful lives that last the half hour or so it takes to bring groceries home from the market, but which possess a second life as refuse that can last a thousand years or more.

Flocks of flying immortal bags are a signature element and a unique hallmark of the disposable age of plastic—a trash challenge Waring and his White Wings never had to deal with or imagine. And yet, despite that, and despite the noise and scale and stench (which really isn’t all that bad, except on the days the sanitation engineers “sweeten” the fill with sewage sludge to jump-start methane production), there is a weirdly beautiful aspect to this place, even to the strange plastic flock flapping and twisting above. To perceive this side of the landfill, one need go no farther than the expression on Big Mike Speiser’s face when he considers his workplace. “We accomplish something here every day,” he says. “It can be strange, it can be loud, but we’re proud of this place, proud of what we do. There is a kind of beauty here, or there will be someday.” He gestures at the oak trees planted in the distance on older sections of Garbage Mountain. “Someday all this will be a park.”

It’s clear the BOMAG master takes pride in Puente Hills’s reputation for being a well-run Disneyland of dumps. Even the neighbors who complain about smells and dust and toxic leaks concede that much (which isn’t to say they share Big Mike’s love of the place—they can’t wait for it to shut down). But Big Mike revels in being a landfill ambassador, talking with the press, demonstrating his driving skills for a National Geographic film crew, chatting with tour groups. He has represented Puente Hills in years past at the national trash Olympics, a not-quite-yearly event sponsored by the Solid Waste Association of North America. This is a gathering of heavy equipment operators from the nation’s waste-management departments and companies, who compete in a series of Olympic-style events set up at a host landfill. At this combination rodeo and monster-truck rally, the contestants must perform various feats of “trash-tacular” skill with their big machines: pass through orange cones with only four inches of clearance on either side, navigate an obstacle course, do some precision blade drops and push a load of gravel to an exact location without spilling. Big Mike has several gold medals to his credit. His colleagues have to point this out, as he won’t; he just nods shyly in acknowledgment once the subject is disclosed.

After the competition, the large men of the landfill fraternity—most of them seem to share Big Mike’s mountainous physique—gather to cool off over a cool drink and to swap stories about the weird things that inevitably turn up at landfills. There’s the mounted deer heads with their glassy eyes and broken antlers, the yellowed dentures scattered in the debris, the occasional bowling ball, the coffin (an empty discard), the mannequins (those always give the dump workers a start, arms or heads poking up out of the cans and Hefty bags). And there are the real bodies, too—because what better place could there be to dispose of the evidence of a serious crime? Puente Hills has had its share: the skull found in the suitcase, the body rolled up in a rug, the rumors of ritual crimes in adjacent Turnbull Canyon, the bloody Santeria shrine found nearby. Then there was Robert Glenn Bennett, who disappeared February 16, 1983, from his maintenance supervisor job at the sanitation district’s water reclamation plant next to the landfill. The fifty-one-year-old never showed up for a part-time bartending gig that Wednesday night after he finished at the plant; witnesses said he argued earlier with a gardener on his staff, who was angry at being denied a promotion. The gardener had a record of minor drug, theft and vandalism offenses, of threatening fellow employees and of exposing himself on the job. Blood matching Bennett’s type was found in the parking lot and on a dump truck, and the gardener, John Alcantara, became the immediate prime suspect. But despite an extensive and unpleasant search of mounds of garbage at the landfill, which police detectives figured to be a likely place for Alcantara to have stashed both body and murder weapon, no evidence could be found linking him to Bennett’s disappearance (or, for that matter, to prove conclusively that Bennett was dead). Twenty-five years would pass before the case would be solved and Alcantara would be convicted of the murder. A witness finally came forward and told police that Alcantara confessed to shooting Bennett in the head, dismembering his body, and then, as the police always suspected, the body had been buried at the adjacent landfill. That’s one of the darker legacies of Puente Hills: What’s left of Robert Bennett remains there to this day, hidden beneath thousands of tons of trash in the Main Canyon section of the landfill, the oldest and deepest zone of Garbage Mountain.

These are the stories that everyone asks about, the weird, the dark and the unusual discoveries mixed in with the refuse. But that’s not what’s revelatory about any landfill’s contents, Big Mike says. The truly thought-provoking part of the business as he sees it is the endless tide of ordinary, everyday stuff streaming into the place, items that are not really trash at all: the boxes of perfectly new plastic bags, still on the roll, tossed because the logo on them was outdated. Or the cases of food that turn up from time to time, perfectly usable and brand-new, yet discarded as if they had no use. Clothes of all types, some worn and torn but others seemingly pristine, are common. There are whole cans of paint (a forbidden, toxic item in landfills, though they arrive mixed in the household trash, difficult to detect), trashed because someone didn’t like the custom color that, once mixed, could not be returned to the paint store. And there is the furniture—tons of it, much of it ratty and too far gone, but a surprising amount of it perfectly serviceable, at least until those chairs and couches and coffee tables meet Big Mike’s BOMAG, the great democratizer of trash. Finally, poignantly, there are the old letters and photo albums, the vintage costume jewelry and ancient report cards in their brown manila envelopes. They are accompanied by sagging cardboard boxes labeled “important papers,” though they aren’t important to anyone anymore. This is the material that gets thrown away after someone dies. This is the world in which Big Mike plays king of the hill, and he sees what few people see, the fate of our most precious possessions, and how quickly, how easily, they become redefined as trash, deservedly or not. Someday, they might be treasures again, when the landfill reaches a great age and the broken but often still identifiable items within it become artifacts awaiting an archaeologist’s pick and brush. But that process takes a very long time, hundreds or thousands of years to turn mundane pieces of broken crockery into valuable artifacts. The more immediate process, the one Big Mike sees every day, is the one where treasures, our treasures of today, are used to construct a trash mountain.

Working there has changed him, he says, compelling him to think about how he and his family live, what they buy, what they waste. So many people buy so many things that they just throw away a year or two later—things that look great on a TV commercial, that promise to make life better or easier or more fun. Then those must-have products break or wear out, or simply wear out their welcome, and they enter Big Mike’s domain.

The irony is that Big Mike’s domain, with its unrivaled ability to hide seamlessly all that waste, empowers even more wasting. The landfill solution to garbage took away the slimy stench of the old throw-it-in-the-streets disposal, the smoking pall of the old incinerators, the noisome piggeries, the noxious reduction plants spewing out garbage grease, the ugly, seeping open dumps. It took away the obvious consequences of waste and eliminated the best incentives to be less wasteful. The rise of places like Puente Hills turned garbage from an ugly canker staring everyone in the face into a nearly invisible tumor, so easy to forget even as it swelled beneath the surface.

“It’s such a waste,” Big Mike observes. “More people should see what I see here, where everything that’s advertised on TV ends up, sooner or later, and a lot sooner than most people think.”

T

HE GOLDEN

age of television and mass media marketing has been alternately celebrated and condemned for the last half a century for its unprecedented impact on society and culture. Yet one of its most enduring effects—helping bring about an American trash tsunami—is rarely put on the list of mass media goods and evils.

Not that the connection is disputed: Leaders of the industry during its earliest days admitted as much, describing their mission in life as persuading American men, women and children to throw away perfectly good things in order to buy replacements promoted as bigger, bolder and better. The senior editor of

Sales Management

magazine chronicled this when he wrote in 1960 that American companies and media outlets were working together to “create a brand new breed of super customers.” A popular media journal of the day,

Printers Ink

, went further, suggesting the mission of marketers had to be centered on the fact that “wearing things out does not produce prosperity, but buying things does … Any plan that increases consumption is justifiable.” Even President Eisenhower was caught up in the fervor, suggesting that shopping was tantamount to a patriotic act. When asked at a press conference what he thought people should buy to bolster the economy during a brief, mild recession, the president responded, “Buy anything.”

And what a vehicle had emerged to persuade Americans to adopt this buy-more mission. For the first time ever, visually compelling moving, talking images were being beamed directly into their homes, free of charge, though not free of commercial messages—a transformative moment that rapidly shifted American popular culture into a round-the-clock tool for selling things. A new marketing industry began speaking about television viewers as a “captive audience” in whom it could instill “artificial” and “induced” needs—those are the terms they casually tossed about—for products no one had ever before considered a necessity. Their tirelessly upbeat portrait of American prosperity, the good life and “progress” made it quite clear that the American Dream was best achieved through buying the latest and greatest cars (preferably several per household), toothpaste and gadgets of all sorts.

This was the moment in which the Depression-era version of the American Dream—which held that hard work, diligent saving and conserving resources paved the road to the good life—began to fade, surpassed by the notion that the highest expression and measurement of the American Dream lay in material wealth itself, the acquisition of stuff. This was the moment when the perceived power to move nations and economies shifted from the ideal of the American citizen to the reality of the American consumer. The phrase “vote with your wallet” entered the public consciousness in this era, elevating the act of spending money from unfortunate necessity to civic virtue.

This change did not happen in secret, unnoticed and unremarked upon. On the contrary, visionaries at the time saw clearly what was about to unfold and called it out—or, more often, celebrated it. The quote that best sums up the economic ethos of the day comes from J. Gordon Lippincott, who pioneered the modern fields of product design and corporate branding. An engineer by training, his marketing and design company’s creations included the iconic Campbell’s Soup label, Chrysler’s “Pentastar” emblem, Betty Crocker’s trademark spoon and the distinctive, stylized “G” of the General Mills cereal logo. Lippincott made this telling observation in 1947:

Our willingness to part with something before it is completely worn out is a phenomenon noticeable in no other society in history … It is soundly based on our economy of abundance. It must be further nurtured even though it runs contrary to one of the oldest inbred laws of humanity, the law of thrift.

Lippincott’s assertions would have sparked doubts about his sanity had they been uttered in Colonel Waring’s day at the turn of the last century, when waste was public enemy number one, or in 1932, as the Great Depression crushed working Americans and the amount of trash generated by families reached record lows because every scrap of wood, paper and food was precious, and every tool and product had to be used, reused and repaired many times before anyone would consider consigning it to the trash. But Lippincott’s era came in the very different boom times that followed victory in World War II, with America the last great power left standing and whole. His words became a marketer’s battle cry signaling a break with the past. He plainly acknowledged that the disposable, thriftless lifestyle he championed ran counter to the most basic human instincts and recent world history, yet he urged its embrace as part of the postwar belief that America—its resources, its wealth, its potential—had reached a state that had no real limits. What does waste matter in the America of Lippincott’s imagination, with its infinite “economy of abundance”? The more we waste, in his view, the more stuff his clients could sell, the more consumers would buy, and the more prosperous America would become.

Failure

to waste was the enemy. If only Americans would waste more, they would boost production, enrich businesses and create more jobs—that was Lippincott’s vision, and it was embraced by most of the nation. The only way to defeat such an economy, he argued, was for consumers to lose their desire to consume in ever greater quantities.