Gallipoli (57 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

In the next bed, another soldier, in his own delirium, is singing a series of comic songs, which, while amusing other patients in the ward, drives Silas madder still. He nevertheless manages to record of his ward:

Here as elsewhere Death stalked â four of my comrades passed out within a few hours of each other â an inert mass covered with the Union Jack is borne away â thus, one by one, they passed into the Infinite, leaving behind a name that shall ever ring glorious.

As I look into the distant future when the sound of guns is but an echo of the past, in grand array shall I see the spirits of these my comrades marching past, who in the greatness of their souls have handed to future generations a fuller, deeper meaning of the word Patriotism.

89

Some of the other men of Monash's 4th Brigade are coping a little better than Ellis and the hundreds of other men who have been carried down the hill and loaded onto steamboats. Instead of being shocked by the constant hail of shells that mar their new life in this alien place, they have made a game out of it. As Colonel Monash himself records, âWe have been amusing ourselves by trying to discover the longest period of absolute quiet. We have been fighting now continuously for 22 days, all day and all night, and most of us think that absolutely the longest period during which there was absolutely no sound of gun or rifle fire, throughout the whole of that time, was ten seconds. One man says he was able on one occasion to count fourteen, but none believed him. We are all of us certain that we shall no longer be able to sleep amid perfect quiet, and the only way to induce sleep will be to get someone to rattle an empty tin outside one's bedroom door ⦠the noise is much greater at night than in the daytime.'

90

18 MAY 1915, PLEASE, SIR, I WANT SOME MORE

âIt is never difficult,' the most celebrated English comic novelist of his day, P. G. Wodehouse, would famously write, âto distinguish between a Scotsman with a grievance and a ray of sunshine.'

91

There is as little confusion when it comes to Kitchener when he is displeased â which is mostly â and it is rarely clearer than in his communications this morning with General Hamilton, who two days before has had the colossal temerity to ask for more troops â

two

more Army Corps at minimum, to replace the men lost! â to break the impasse. Kitchener tersely responds:

I AM QUITE CERTAIN THAT YOU FULLY REALIZE WHAT A SERIOUS DISAPPOINTMENT IT HAS BEEN TO ME TO DISCOVER THAT MY PRECONCEIVED VIEWS AS TO THE CONQUEST OF POSITIONS NECESSARY TO DOMINATE THE FORTS OF THE STRAITS, WITH NAVAL ARTILLERY TO SUPPORT OUR TROOPS ON LAND, AND WITH THE ACTIVE HELP OF NAVAL BOMBARDMENT, WERE MISCALCULATED.

A SERIOUS SITUATION IS CREATED BY THE PRESENT CHECK, AND THE CALLS FOR LARGE REINFORCEMENTS AND AN ADDITIONAL AMOUNT OF AMMUNITION THAT WE CAN ILL SPARE FROM FRANCE â¦

I KNOW THAT I CAN RELY UPON YOU TO DO YOUR UTMOST TO BRING THE PRESENT UNFORTUNATE STATE OF AFFAIRS IN THE DARDANELLES TO AS EARLY A CONCLUSION AS POSSIBLE, SO THAT ANY CONSIDERATION OF A WITHDRAWAL, WITH ALL ITS DANGERS IN THE EAST, MAY BE PREVENTED FROM ENTERING THE FIELD OF POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS.

92

THE TURKISH OFFENSIVE

The Australians at Anzac hold the most extraordinary position in which any army has ever found itself, clinging, as they are, to the face of the cliffs. Roughly the position consists of two semicircles of hills, the outer higher than the inner. They are extremely well entrenched and cannot be driven from their position by artillery fire or frontal attacks ⦠The Turks are entrenched up to their necks all round them.

1

Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, The Uncensored Dardanelles

Their beauty, for it really was heroic, should have been celebrated in hexameters not headlines ⦠There was not one of those glorious young men I saw that day who might not himself have been Ajax or Diomed, Hector or Achilles. Their almost complete nudity, their tallness and majestic simplicity of line, their rose-brown flesh burnt by the sun and purged of all grossness by the ordeal through which they were passing, all these united to create something as near to absolute beauty as I shall hope ever to see in this world.

2

Compton Mackenzie, novelist and member of General Hamilton's staff at Gallipoli

18 MAY 1915, FROM ABOVE ANZAC COVE, ATTACK OF THE WILD TURKS

Mustafa Kemal is restless, roaming â¦

He has just received word that Brigadier-General Esat â under order of General Enver and General Liman von Sanders â will be taking more hands-on control of the recently formed Northern Group and moving into the headquarters at Kemalyeri. Yes, the name will remain, but Colonel Mustafa Kemal is to move his 19th Division headquarters to Battleship Hill, where he will command the northern sector of the Northern Group. And one more thing â¦

General Enver has made clear after his visit to the Peninsula that nothing less than the infidels being pushed off the Turkish homeland is acceptable to the government in Constantinople.

The objective of the attack,

regardless of losses

, is really quite simple: âAttack before day-break, drive the ANZAC troops from their trenches, and follow them down to the sea.'

3

With 30,000 soldiers secretly amassed in the preceding days and suddenly on the charge, they should be able to dislodge the invaders, who cannot number more than 20,000. After all, they only need to break through at one strategic point â say, Quinn's Post â and the rest of the Allied defences should fold in on themselves.

God help the Anzacs, because Allah won't.

Among the Anzacs, on this morning of 18 May, it is noted: for some reason the Turks are not firing at them today. No bullets, no constant explosions of shells all around. You can hear the birds singing.

(Well, mostly anyway. In the mid-morning, a flock of storks is unwise enough to fly over the Australian trenches, at which point furious firing skyward breaks out. Two of them fall in positions where they can be recovered by the Diggers, meaning a welcome change from bully beef tonight.)

But then the silence returns.

And something else is odd. Walking around the trenches that afternoon, General Birdwood notices a lot of movement in the Turkish lines.

Could they have something planned? His senior officers agree it is likely. Even though the Allies have only been on these shores for a little over three weeks, they already recognise that anything out of the ordinary is usually a prelude to an attack. And as this is

so

out of the ordinary, perhaps it is a big attack. As a precaution, General Birdwood orders reserves to come forward and be in position to move quickly if required.

Their suspicions are confirmed when a pilot of the Royal Naval Air Service flies over the Peninsula at a safe height and sees âtwo of the valleys east of the ANZAC line are packed with Turkish troops, densely crowded upon the sheltered slopes'.

4

But it gets worse. When a second plane is sent up to confirm the report, its pilot not only sees the same masses of troops but also spots four steamers unloading even

more

soldiers on the European shore of the Dardanelles. Reports roll in throughout the day, bringing news of âconsiderable bodies of mounted troops and guns'.

5

Just what on earth are the Allies about to face? Against the 17,500 men the Anzacs can muster, it looks as though there must be 40,000 of the brutes about to come at them. Can it really be that bad?

6

They are not long in finding out.

On the Anzac perimeter, at 5 pm, the air is suddenly filled with a distant boom, closely followed by a whistling sound, before a weird screeching comes in an ever higher crescendo and then ⦠a massive explosion. And then another, and another, and another. More shells than ever before start falling, âchiefly on the Australian line from the Pimple northwards to Courtney's'

7

⦠And it is not just those at Anzac Cove who can hear it. Off the coast, the next contingent of the Australian Light Horse are arriving in their transports and crowd the decks, transfixed by the ârumbling of heavy artillery'

8

that rolls over them. As they get closer, they can see âthe intermittent flashes of the guns'

9

in the gathering dusk. They won't be able to land tonight, but even this small glimpse of action is enough to:

Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood,

Disguise fair nature with hard-favour'd rage;

Then lend the eye a terrible aspect;

(Shakespeare,

King Henry V

, Act 3, Scene 1)

They cannot

wait

to land.

Just before 5.30 pm, it happens. Behind the Turkish trenches closest to Courtney's Post, three Turkish soldiers load a howitzer and follow their strict routine, their Sergeant shouting, â

Hazirol!

â Ready!' and then, â

AteÅ!

â Fire!'

An instant later, the howitzer erupts and the shell heads skyward, a searing streak of flame, before lobbing towards the Australian lines. Of course, the Turks have no idea exactly where it will land, only that it will be right among those who had been raining exactly the same kind of devastation on them.

Carter is organising the soldiers in his trench to get into better sniping positions, willing the barrage to stop. Even over the sound of so many other exploding shells, he now hears a whistling, getting louder, screeching now, squealing â¦

Is this it?

⦠He involuntarily stiffens his whole body, as if that might save him. The shell lands just a few yards away, and explodes â¦

In his dugout, Bean records that the sound of Turkish fire is so overwhelming that it has âgrown to a roar like that of a great stream over a precipice'.

10

As his position is close to the signals office â the communications nerve centre for all of Anzac Cove â he heads over to seek more information. The office is doing exactly that as he arrives, checking with all the brigades and their battalions on the frontline. All bar 2nd Battalion have reported that, despite the unprecedented barrage, everything is under control. Bean waits, as they all do, for an operator to track them down.

Soon a report comes crackling down the line: all is âOK'.

âTell him I wanted to know,' Brigadier-General âHooky' Walker says, âwhether in view of the firing there is anything to report.'

11

âHe says it's only the Turks firing.'

12

Barely worth mentioning when you put it like that. Just after midnight, Bean goes back to bed.

Nevertheless, because of the air intelligence that the Turkish troops are massing, all soldiers on the frontline at Anzac are instructed to âstand to arms at 3 am'

13

instead of the usual 3.30 am.

The strangest thing? Despite the horror of what the men are experiencing as still the barrage grows in intensity, more than a few soldiers are struck by the vivid wonder of what they are witnessing.

âThe scene during this shelling was a wild but beautiful sight,' Archie Barwick would recount. âA mass of bursting shells, our own & the Turks' & as they burst they threw out different coloured flashes, some golden some pink, yellow, blue, dark & light red & all different shades from the different sorts of explosives they were using.'

14

It is all more spectacular than the fireworks on Empire Day back home!

Suddenly, however, it stops and there is a strong sense that something big is about to happen.

Everyone ready?

Among the four divisions of Turks, the soldiers crouch, waiting for the bugle to sound.

Among the Anzacs, there is a last-minute check of ammunition, bayonets and rifles. Everyone knows that there will shortly be a rush at them â the only thing yet to be determined is just how big it will be.

And suddenly a piercing bugle call cleaves the night.

From the Turkish trenches come thousands of voices crying â

Allah! Allah! Allah!

', and here they come, spectres rising from the ground in front, and then suddenly looming large as the first wave rushes towards the Anzac trenches â¦

And,

now

â¦

The shout goes up, the triggers are pulled, and the night is filled with the chattering roar of dozens of machine-guns and thousands of rifles, together with the boom of the mountain guns, followed by the screams and groans of mown-down Turks.

Bizarrely, even above such uproar and agony the strangled sounds of Turkish bands playing martial tub-thumpers can also be heard as whole lines of Turkish soldiers continue to run forward with calls of â

Allah!

'.

It is slaughter, pure and simple. With such a mass of men coming at them, at such a close range, the Anzacs in the frontline simply cannot miss, and most bullets find a billet in a Turk. Soon the succeeding waves of attackers tumble over the bodies of the dead men who have gone before.

So fearful is the damage being done by the Allied frontline soldiers that those behind plead, âCome on down and give us a go ⦠I'm a miles better shot than you.'

15

When that doesn't work, in one trench so crammed that not everyone can get up on the fire-step, one bloke behind and below is heard to offer â5 quid to any of youse who will give me your spot'.

16

As to Allah, no one has the least sympathy for either the deity or the men who are endlessly shouting his name. They continue to charge forward, â

Allah! Allah! Mohammed! Allah!

'.

âYes,' an infantryman roars as he shoots the Turkish soldiers down, âyou can bring them along too!'

17

As the Turks continue to charge, the Australians can even sit on the parapets to make themselves more comfortable as they shoot. It is all just so âdead easy â just like money from home'.

18

The heaviest of the Turkish attacks are around 400 Plateau, Quinn's and Courtney's Post. The last is held by the 14th Battalion, but, after throwing bombs into a trench bay, one mass of Turkish soldiers actually captures a part of it. For the Australians, for the whole of Anzac Cove, the situation is now critical. The trench

must

be recaptured, and quickly.

The man on the spot is none other than Private Albert Jacka, the wiry 22-year-old timber worker from Wedderburn, Victoria, who is in a firing bay right where the Turks have broken through. As the emergency escalates, Lieutenant Keith Crabbe from the 14th Battalion HQ rushes up, only to be shouted at by Jacka to stop â if he comes any further, he will be killed by the Turks around the corner.

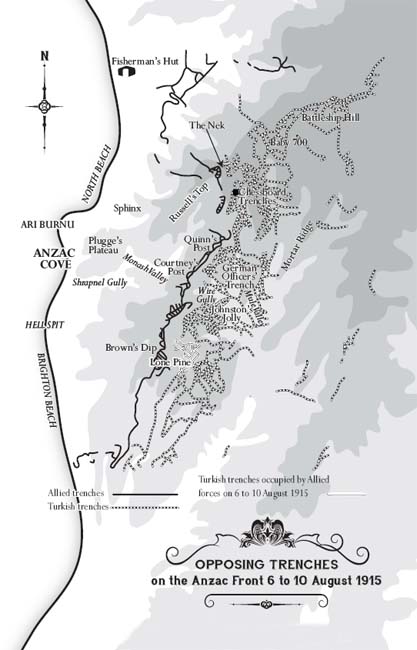

Opposing trench lines, 6â10 August 1915, by Jane Macaulay

âIf you are given support,' Lieutenant Crabbe shouts to Jacka over the continuing cacophony of fire, âwill you charge the Turks?'

âYES!' Jacka shouts back.

19

As confident as Lieutenant Crabbe is of Jacka's abilities â he has always been a soldier who'd sooner a fight than a feed, a donnybrook ahead of a drink â still he sends four Australian soldiers forward to support the Victorian in the zigzagging trenches.

Jacka himself gives the call and then takes the lead. The five Australian soldiers rush forward and, through brutal use of their bayonets, put paid to the first lot of Turkish soldiers they come to, losing two of their own in the process.

Regrouping, Jacka and Lieutenant Crabbe decide on a new plan, their faces illuminated by the flickering light of exploding shells, their voices having to rise above the continuing onslaught. It will later be said of Jacka that he was âstrong, completely confident, entirely fearless, bluntly outspoken, not given to hiding his light under a bushel ⦠likely to be overlooked by his superiors, until it astonished them in some emergency',

20

and this is just such an occasion. For though of lower rank, it is Jacka who commands. At his suggestion, Crabbe and the two surviving soldiers will feint an attack at one end while he will try to get at the Turks from another angle, working his way through the maze of trenches to a point he and Crabbe know. Then, at the time set, they will throw bombs where the Turks are thought to be. In the confusion and carnage, the waiting Jacka will climb up and over into no-man's-land, race across and jump back among the Turks.