Galileo's Daughter (44 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Suor Maria Celeste probably received her apprenticeship as an apothecary under the nuns and visiting doctors who staffed the convent’s infirmary. Her more basic schooling in letters and Latin, on the other hand, undoubtedly came from her father, in whatever time he could spare during her formative years, for it is clear that no one at San Matteo surpassed her in language skills. Even the abbesses sought her out to write important letters of official business.

In Galileo’s own scientific correspondence through the autumn of 1633, he circulated among his friends certain proofs relating to the strength of materials. With their permission, and to their delight, he incorporated some of their additions and suggestions into the text for the second day of

Two New Sciences.

Galileo would later judge

Two New Sciences

“superior to everything else of mine hitherto published,” because its pages “contain results which I consider the most important of all my studies.” By his own reckoning, then, his conclusions on resistance and motion outweighed all the astronomical discoveries that immortalized his name. Surely Galileo prided himself on having been the first to build a proper telescope and point it toward the sky. But he believed his own greater genius lay in his ability to observe the world at hand, to understand the behavior of its parts, and to describe these in terms of mathematical proportions

*

While he worked on the dialogue for the beginning of

Two New

Sciences,

Galileo also wrote a play. He sent it to Suor Maria Celeste for performance by the nuns—apparently for the anticipated entertainment of Her Ladyship Caterina Niccolini, the wife of the Tuscan ambassador, who was still intent on visiting the convent. Unfortunately, nothing survives of Galileo’s religious drama except his daughter’s mention of it in thanks. “The play, coming from you,” she wrote after reading the first act, “can be nothing if not wonderful.”

In Rome, Ambassador Niccolini told Urban VIII that Galileo had proved himself to be a model prisoner in Siena by demonstrating obedience to the pope and the Holy Office. Urban weighed this claim against impeachments of archbishop Piccolomini that reached him from clerics in Siena. It seemed that the archbishop quite often invited various scholars to his table, the better to enrich the intellectual repartee so beneficial to Signor Galilei’s peace of mind. In other words, instead of holding Galileo prisoner as a confessed heretic, Piccolomini indulged him as a guest of honor.

“The Archbishop,” an anonymous hand informed officials in Rome, “has told many that Galileo was unjustly sentenced by this Holy Congregation, that he is the first man in the world that he will live forever in his writings, even if they are prohibited, and that he is followed by all the best modern minds. And since such seeds sown by a prelate might bear pernicious fruit, I hereby report them.”

From

Arcetri

My soul and

its longing

It rained all across Tuscany through the end of October 1633 and on into November. The dampness aggravated Galileo’s arthritic pains, deepened Suor Maria Celeste’s lassitude, cast its dreary pall over all their expectations. Suor Caterina Angela, the former mother abbess at San Matteo, died in the wet autumn weather, and the nuns buried her in the convent cemetery in the rain.

I am the resurrection, I am the life; he who believes in me, even if

he die, shall live; and whoever lives and believes in me, shall never

die. [Office for the Dead, Canticle of Zechariah]

The other sick nuns in the infirmary held on. Galileo failed to send the partridge for them, though not through lack of trying. This late in the hunting season, not a single one could be bagged anywhere. Suor Maria Celeste, for her part, had no better luck procuring the tiny ortolan buntings that Galileo craved and could not get in Siena.

Gray partridge

“I delayed writing this week,” she apologized, “because I really wanted to send you the ortolans, but in the end none have been found, and I hear they fly away when the thrushes arrive. If only I had known this desire of yours, Sire, several weeks ago, when I was racking my brain trying to think of what I could possibly send you that might please you; but never mind! You have been unlucky in the ortolans, just as I was foiled by the gray partridges, because I lost them to the goshawk falcon.”

The heavy rain made it impossible to set the broad beans in his garden, she said, but fair weather must come again, and with it his return. “I send you no pills because desire makes me hope that you must soon arrive here to claim them in person: I am all eagerness to hear the resolution that will reach you this week.”

The resolution did not come, however. Galileo grew cranky with waiting, and so dependent on his daughter’s letters that he scolded her when they failed to arrive often enough to soothe him.

“If only you could fathom my soul and its longing the way you penetrate the Heavens, Sire,” she began on November 5, “I feel certain you would not complain of me, as you did in your last letter; because you would see and assure yourself how much I should want, if only it were possible, to receive your letters every day and also to send you one every day, esteeming this the greatest satisfaction that I could give to and take from you, until it pleases God that we may once again delight in each other’s presence.”

Then she told him how she had secured his coveted ortolans after all—through a bird keeper in the service of the grand duke. Any moment now she would dispatch Geppo to the game-rich acres of the Boboli Gardens behind the Pitti Palace, armed with a floured box in which to pack the delicate birds and deliver them straight away to Signor Geri. But when Galileo thanked her for them a few days later, he said nothing of his own flight from Siena.

“I must tell you first how astounded I was,” she wrote the following Saturday, November 12, “that you made no mention in your most recent letter of having received any word from Rome, nor any resolution regarding your return, which we had so hoped to have before All Saints’ Day [November 1], from what Signor Gherardini led me to believe. I want you to tell me truly how this business is progressing, so as to quiet my mind, and also please tell me what subject you are writing about at present: Provided it is something that I could understand, and you have no fear that I might gossip.”

Suor Maria Celeste necessarily understood the semisecret nature of her father’s works in progress. In fact, some of the materials removed from II Gioiello during Galileo’s trial concerned his writing on motion, including the manuscript for the third day of

Two New Sciences,

which he had roughed out before he left for Rome. Although Galileo would not have deemed these particular documents incriminating, he had reason to fear their needless destruction.

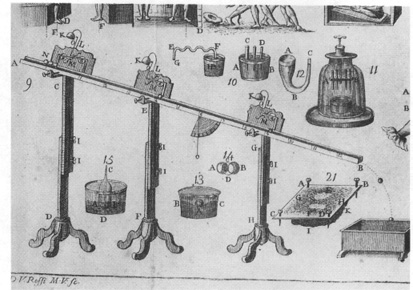

Day Three’s treatment of uniform and accelerated motion bears witness to the untold number of Paduan hours Galileo spent tracking the course of a small bronze ball down the groove of an inclined plane to probe the mystery of acceleration. Unable to experiment fruitfully with freely falling objects, Galileo built his inclined-plane apparatus so he could control fall, stopping the action at will, making precise measurements of time and distance all the while. Salviati, who claims in

Two New Sciences

to have assisted Galileo occasionally in these efforts, describes them to Sagredo and Simplicio:

We rolled the ball along the channel, noting, in a manner presently to be described, the time required to make the descent. We repeated this experiment more than once in order to measure the time with an accuracy such that the deviation between two observations never exceeded one-tenth of a pulse-beat. Having performed this operation and having assured ourselves of its reliability, we now rolled the ball only one-quarter the length of the channel; and having measured the time of its descent, we found it precisely one-half of the former. Next we tried other distances, comparing the time for the whole length with that for the half, or with that for two-thirds, or three-fourths, or indeed for any fraction; in such experiments, repeated a full hundred times, we always found that the spaces traversed were to each other as the squares of the times, and this was true for all inclinations of the plane . . . along which we rolled the ball.

Just as Copernicus had discerned the configuration of the solar system with no telescope to guide him, Galileo arrived at this fundamental relationship between distance and time without so much as a reliable unit of measure or an accurate clock. Italy possessed no national standards in the seventeenth century, leaving distances open to guesstimate gauging by flea’s eyes, hairbreadths, lentil or millet seed diameters, hand spans, arm lengths, and the like. Even a

braccio

differed in dimension depending on whether it was measured in Florence, Rome, or Venice, and so Galileo delineated his own arbitrary units along the length of his experimental apparatus. As long as these units matched one another, he could use them to establish fundamental relationships.

To clock the rolling time of the balls, Galileo literally weighed the moments. “For the measurement of time,” Salviati continues in his experimental description, “we employed a large vessel of water placed in an elevated position; to the bottom of this vessel was soldered a pipe of small diameter giving a thin jet of water, which we collected in a small glass during the time of each descent, whether for the whole length of the channel or for a part of its length; the water thus collected was weighed, after each descent, on a very accurate balance [against grains of sand]; the differences and ratios of these weights gave us the differences and ratios of the times, and this with such accuracy that although the operation was repeated many, many times, there was no appreciable discrepancy in the results.”

Artistic rendition of Galileo’s incline plane

Although this account reveals stunning experiments that promise to open a new window on philosophy, Salviati cannot be shaken from his recently acquired pedantic monotone, which threatens to establish an irreparable split, if not between science and religion, then between science and poetry.

The ball-and-plane trials provided the tedious yet triumphant prelude to the truth about falling, which Galileo expressed in

Two

New Sciences

as a series of theorems. He did not use the convention of algebraic analysis that later allowed his rules to be pared down to a few letters and symbols, but expressed his findings as geometric ratios, and wrote out his proofs in dense prose accompanied by letter-labeled line drawings in the style of the ancient Greek mathematicians.

All the motions discussed on the third day of

Two New Sciences

are “natural” ones, since the experimental objects simply roll or drop, instead of being thrown with force. Not until Day Four (which Galileo would complete several years later, in 1637) do the “violent” movements of bullets and other projectiles come up for discussion. Here Galileo displays his singular insight in breaking motions into their separate components. For he shows that any cannonball fired from a mortar, for example, or any arrow shot from a bow, combines two vectors: the uniform forward thrust of the propulsion and the downward acceleration of free fall.