Galileo's Daughter (24 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

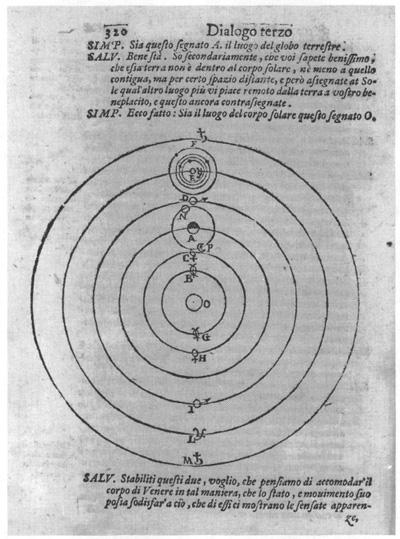

Diagram from Day Three of Galileo’s

Dialogue

demonstrating the Copernican system

He presented the new sunspot evidence on Day Three of the

Dialogue,

the day devoted to the discussion of the Earth’s annual motion. It came up right after a spirited demonstration of the planetary positions, in which Salviati showed how the errant wanderings of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn could all be explained by the Earth’s plying a yearly orbit, between the orbits of Venus and Mars, around the Sun.

“But another effect,” Salviati adds without pausing for breath, “no less wonderful than this, and containing a knot perhaps even more difficult to untie, forces the human intellect to admit this annual rotation and to grant it to our terrestrial globe. This is a new and unprecedented theory touching the Sun itself. For the Sun has shown itself unwilling to stand alone in evading the confirmation of so important a conclusion, and instead wants to be the greatest witness of all to this, beyond exception. So now hear this new and mighty marvel.”

And he proceeds to describe how the sunspots alter their apparent path, from the straight line that could be observed only two days out of every 365 (at the summer and winter solstices), to an arc that curves upward for half the year and downward for the other six months. Anyone who clung to the Ptolemaic system— who insisted the Sun spun around the Earth every day—now had to explain why the sunspots changed the angle of their path according to an annual cycle, and not a daily one. Some Aristotelian stalwarts might dredge up the old dismissal of the sunspots as vain illusions of the telescope lenses. More serious and scientific followers of Ptolemy, however, would have to spiral the Sun through the most complex gyrations imaginable, in order to save these newly recognized appearances in a geocentric and geostationary system.

Salviati’s explication of the sunspot connection fills only ten pages of dialogue, including a couple of diagrams to help Sagredo and Simplicio grasp the concept. The three discussants thus find ample time on the third day to consider other imponderables—the size and shape of the firmament, for example—and to converse in awe about the confounding grandeur of space.

Responding to Simplicio’s Aristotelian vision of the Earth as the center of the world, the center of the universe, the hub of the stellar sphere, Salviati proposes something vaster and vaguer: “I might very reasonably dispute whether there is in Nature such a center, seeing that neither you nor anyone else has so far proved whether the universe is finite and has a shape, or whether it is infinite and unbounded.”

This very modern idea of a universe without end had occurred to Copernicus but also helped kindle the fire that executed Giordano Bruno, as Galileo knew. He dropped the subject quickly yet returned again and again in the

Dialogue

to the evident enormity of the heavens.

Copernicus had pushed the stars away to unimaginable distances to explain their constancy in contrast to the planets. The reason the stars never seemed to rock this way or that as the Earth traveled all around the Sun over the course of the year, Copernicus explained, was that they lay too far away for any shift in position, or parallax, to be perceived. Galileo agreed, and furthermore predicted that improved observations through powerful future instruments would one day reveal this annual stellar parallax.

*

Simplicio and his fellow Aristotelian philosophers really hated the big, unwieldy universe of Copernicus. They could not believe that God would have wasted so much space on something of no possible use to man.

“It seems to me that we take too much upon ourselves, Simplicio,” counters Salviati, “when we will have it that merely taking care of us is the adequate work of Divine wisdom and power, and the limit beyond which it creates and disposes of nothing. I should not like to have us tie its hand so. . . . When I am told that an immense space interposed between the planetary orbits and the starry sphere would be useless and vain, being idle and devoid of stars, and that any immensity going beyond our comprehension would be superfluous for holding the fixed stars, I say that it is brash for our feebleness to attempt to judge the reason for God’s actions, and to call everything in the universe vain and superfluous which does not serve us.”

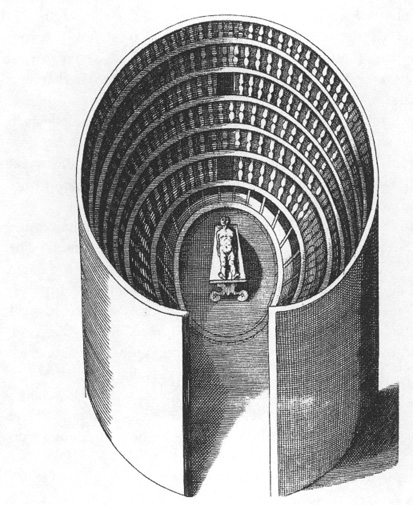

The operating theater at the University of Padua

The quick-witted Sagredo jumps in at this point, bristling that even the remote stars may serve a man in ways he cannot fathom. “I believe that one of the greatest pieces of arrogance, or rather madness, that can be thought of is to say, ‘Since I do not know how Jupiter or Saturn is of service to me, they are superfluous, and even do not exist.’ Because, O deluded man, neither do I know how my arteries are of service to me, nor my cartilages, spleen, or gall; I should not even know that I had gall, or a spleen, or kidneys, if they had not been shown to me in many dissected corpses.”

Sagredo’s frequent anatomical analogies throughout the

Dialogue

recall that Andreas Vesalius published his revelations about human anatomy,

On the Fabric of the Human Body,

in 1543—the same year as Copernicus’s

On the Revolutions of the Heavenly

Spheres,

and with just as much affront to Aristotle. Even while Galileo sat writing the

Dialogue

nearly a century later, Aristotelians still clung to the heart as the origin of the nerves, though Vesalius had followed their course up through the neck to the brain. Vesalius, who took his medical degree at Padua and lectured all over Italy, had also staged sensational popular demonstrations showing the male and female skeletons to contain the same number of ribs, thus defying the widespread belief, based on the Book of Genesis, that men came one rib short.

Although Galileo had left his own medical studies behind by the time he began teaching at Padua in 1592, he undoubtedly attended human dissections by torchlight in the university’s tiered anatomical theater, the world’s first such facility, where the cadaver could be raised through a trapdoor in the floor from the canal below, and its body parts burned in a furnace after study. Several of Galileo’s acquaintances on the Padua medical faculty, out of necessity, willed their own mortal remains to the university, to save the anatomists the bother of pillaging the hospitals or begging the bodies of criminals condemned to hang.

“Besides,” Sagredo sputters at last in frustration with those who would limit the majesty of the universe, “what does it mean to say that the space between Saturn and the fixed stars, which these men call too vast and useless, is empty of world bodies? That we do not see them, perhaps? Then did the four satellites of Jupiter and the companions of Saturn come into the heavens when we began seeing them, and not before? Were there not innumerable other fixed stars before men began to see them? The nebulae were once only little white patches; have we with our telescopes made them become clusters of many bright and beautiful stars? Oh, the presumptuous, rash ignorance of mankind!”

Thus, to imagine an infinite universe was merely to grant almighty God His proper due.

The tempest

of our

many torments

All through the autumn of 1629, Galileo gave himself over to the completion of the

Dialogue,

which he finished on Christmas Eve. His health remained strong throughout this period, interrupting his three-month burst of creativity only once, in early November, when Suor Maria Celeste and Suor Luisa treated his brief indisposition by sending him five ounces of their vinegary oxymel concoction and some syrup of citron rind to ameliorate its bitter taste.

Now that Sestilia had assumed the domestic care of Vincenzio through her wedding vows, and also tended lovingly to many of Galileo’s personal needs, Suor Maria Celeste apparently found another way to aid her father. One of her letters suggests that she busied herself recopying his draft manuscript of the

Dialogue.

Sections Galileo had composed at different times in different formats now needed to be handwritten page by page in perfect penmanship for publication, with corrections and additions pasted in as necessary. When Suor Maria Celeste referred to

ritagli

or “clippings” already in her possession during November of 1629, reminding him of additional ones he had promised to send before she could set to work on the whole lot, she more than likely meant pieces of the

Dialogue

that reached her piecemeal. (The book’s original manuscript has not survived, however, nor any description of it that notes whose handwriting it bore.)

On the short fourth—and final—day of the

Dialogue,

Galileo rehashed the “Treatise on the Tides” he had given to Cardinal Orsini in 1616, in which he judged the flux and reflux of the sea to be the inevitable result of the Earth’s two motions, one around its own axis, the other around the Sun: As the Earth turns, its daily spinning conspires with its annual revolution to jar the great oceans. Not only can the moving Earth account for the tides, Salviati indicates in his speeches, but also the tides, by their very existence, reveal the motion of the Earth.

After Simplicio denounces this idea as “fictitious,” the men continue to plumb the confounding complexity of the tides—how they vary in timing, in volume, and in height from one part of the world to another. Salviati suggests that the effort of accounting for these anomalies in the Mediterranean alone led literally to the death of Aristotle: “Some say it was because of these differences and the incomprehensibility of their causes to Aristotle that he, after observing them for a long time from some cliffs of Euboea, plunged into the sea in a fit of despair and willfully destroyed himself.”

The denouement at that day’s end, when it came time for the three characters to close discussion and draw conclusions, demanded delicate diplomacy, for the text of the third and fourth days advanced compelling physical arguments in support of Copernicus, while the overall tenor of the book needed to preserve the spirit of hypothesis, as Galileo had promised Urban it would.

“In the conversations of these four days we have, then, strong evidences in favor of the Copernican system,” sums up the hospitable Sagredo, “among which three have been shown to be very convincing—those taken from the stoppings and retrograde motions of the planets, and their approaches toward and recessions from the Earth; second, from the revolution of the Sun upon itself, and from what is to be observed in the sunspots; and third, from the ebbing and flowing of the ocean tides.”

But Salviati-cum-Galileo, although he has led the discussion in this direction, refuses to endorse Copernicus in the end. He concedes that “this invention“—meaning the heliocentric design— “may very easily turn out to be a most foolish hallucination and a majestic paradox.”

By such equivocation, Galileo offset his persuasive, often passionate defense of Copernicus. At the end of the

Dialogue,

he further sought to please Pope Urban by complying with His Beatitude’s wish to see a reprise of the cicada philosophy from

The

Assayer

—the idea that God and Nature possess boundless means for creating the effects observed by men. But Galileo placed these words in the mouth of Simplicio, where their profundity rang shallow: “As to the discourses we have held, and especially this last one concerning the reasons for the ebbing and flowing of the ocean, I am really not entirely convinced,” balks the staunch Aristotelian;

but from such feeble ideas of the matter as I have formed, I admit that your thoughts seem to me more ingenious than many others I have heard. I do not therefore consider them true and conclusive; indeed, keeping always before my mind’s eye a most solid doctrine that I once heard from a most eminent and learned person, and before which one must fall silent, I know that if asked whether God in His infinite power and wisdom could have conferred upon the watery element its observed reciprocating motion using some other means than moving its containing vessels, both of you would reply that He could have, and that He would have known how to do this in many ways which are unthinkable to our minds. From this I forthwith conclude that, this being so, it would be excessive boldness for anyone to limit and restrict the Divine power and wisdom to some particular fancy of his own.