Fugitives! (2 page)

Authors: Aubrey Flegg

Con’s hand flew to the little dagger that hung at his waist, but the man calmly put his hand on Con’s and said in a low voice: ‘Little lord, I’d hide your pretty dagger before it is taken from you.’

‘Get away from me!’ snapped Con, as he snatched his arm away, looking about for help. People were hurrying through the gate – in a minute he’d be left outside with the beggars and this strange creature.

Con slapped the bear-man’s hand smartly with his reins and urged Macha forward to join the jostling crowd inside the gates.

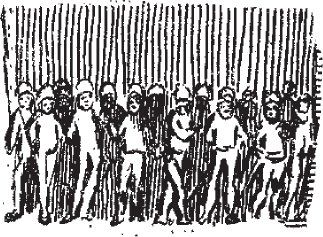

‘Make way for Milord Chichester,’ came the shout. The crowd surged about Con, pressing back to make room on the road. The boy and his pony were pinned against the wall of a house. He could hear the beat of a drum and the tramp of marching feet. Then he saw, first a stickle of pikes swaying down the road ahead, then the pike men’s shining helmets, and behind them a solid phalanx of musketeers, and the captain’s match, a smouldering cord, smoking from the butt of his musket ready to fire it or to light the matches of the other musketeers. Then came a dozen or so archers, their bows strung, quivers of arrows swaying on their backs. Finally, with a clatter of shoes on cobbles came ten or so cavalry officers, their plumed hats making a splash of colour. Con sat riveted, looking at them in amazement and delight. They were even better than he’d imagined. And suddenly, not five paces off, was Sir Arthur Chichester! This was the most powerful Englishman in Ireland. The

man everyone feared. Only yesterday Father had told Con how that very man was trying to hound him from his own land, grabbing Irish land for English settlers, and forcing the native Irish to become Protestants. Indignation swelled up inside Con’s small chest.

At that moment, as if the great man sensed Con’s fury, he turned and looked directly at the boy; hard eyes flashed grim under his glinting helmet and his voice carried easily across the few yards to where Con sat. ‘Where did that young dandelion blow in from?’

Why me?

Con wondered. Then he knew; sitting on his pony in his bright saffron shirt, he stood out like a beacon above the sombre crowd about him.

A lieutenant riding a pace or two behind his captain looked across at Con. ‘A pwetty girl by the look … no … no, it’s a boy, that yellow thing’s a shirt! The savage has dwessed up for you.’ He sniggered. ‘He looks harmless enough.’

But the general’s face was cold. ‘If you had fought these savages you wouldn’t call them harmless!’

Undaunted, the lieutenant called out. ‘Hey you, girlie, what are

you

doing on this side of the Pale?’

This side of the Pale!

In a flash, Con realised what he had done. The Pale – he had crossed it! But where were the wall and the battlements, and the guards in shining armour? That glorified hedge he had seen on the way in, that must be the Pale. He had ridden all this way to see

that

! How could he have been such a fool? Of course, that was the reason for the gate and the guards. He sat there with his mouth open.

The lieutenant shrugged. ‘It doesn’t even speak English,’ he said in disgust and rode on.

re ye going to lie there all day?’ James opened his eyes, then hurriedly closed them again as a douse of cold water splashed across his face. Kathleen, Mother’s maid, reached down and stripped the blanket off him. He grabbed at it, but it was gone. Then she stood over him, hands on hips, stirring him with her foot. ‘Everyone’s gone ’cept you, an’ I’ve got the room to fix.’

re ye going to lie there all day?’ James opened his eyes, then hurriedly closed them again as a douse of cold water splashed across his face. Kathleen, Mother’s maid, reached down and stripped the blanket off him. He grabbed at it, but it was gone. Then she stood over him, hands on hips, stirring him with her foot. ‘Everyone’s gone ’cept you, an’ I’ve got the room to fix.’

James sat up, combing through his hair with his fingers. He looked over to the guest room and saw the open door. He nodded towards it. ‘Where is he?’

Kathleen followed his look. ‘Milord O’Neill’s down with Sir Malachy.’

James remembered his night’s torments.

I must stop thinking of him as ‘Uncle Hugh

’, he told himself.

He’s Hugh O’Neill, the Earl of Tyrone, and no blood relation of mine! I am a de Cashel and we are Normans. We belong with the English. The sooner we break with O’Neill and the native Irish the better

.

He strode over to the water bucket and found it empty. ‘Where’s

my water, Kathleen?’ he demanded.

‘I gave it to you a moment ago!’ she sniggered.

James kicked angrily at the heavy wooden bucket, hurt his toe, and had to limp for the door. Kathleen’s screech of laughter followed him down the stairs.

The cheek of her

, he thought, as he limped down.

Bloody Irish!

Recently, James had been having secret talks with his tutor, Dr Henry Fenton. Dr Fenton had come to the castle a year ago to act as Father’s secretary and as tutor to the castle’s three children, then eleven-year-olds: James and his twin sister Sinéad, and Fion O’Neill, their foster brother. Every day they would have lessons in the great hall, where Father could hear them reciting their work. Mostly, however, Father would nod and doze, catching up on the sleep that his throbbing wound robbed him of at night.

Sinéad had taken an instant dislike to their new tutor and would re-enact the pompous little speech he had given them the day he arrived. ‘My dear young nobles,’ she would imitate, thrusting her hand into the front of an imaginary gown, ‘like your Father, Sir Malachy,’ here she would give an elaborate bow, ‘I come from the oldest of Norman stock, and am a devout if humble Catholic.’ She would copy her tutor’s squirm, sending James and Fion into hoots of laughter. Then she would wag her finger. ‘It’s not me you must respect, but my gown, my degree in law’, and she would stroke the fur of her imagined gown, explaining that it came from ‘only the highest-born rabbit’.

In fact, Dr Fenton was a good teacher. At Father’s insistence, he taught them through English, joking about ‘knowing the language of the enemy’.

But two months ago, after a visit to Dublin, he had surprised them all by suggesting to Sir Malachy that James, ‘as future head of the family’, should come to his house for private lessons in Latin. Sinéad and Fion teased James over the ‘head of the family’ bit, but secretly wondered how James would manage. ‘He can hardly remember the days of the week, let alone Latin!’ scoffed Sinéad.

His first lessons had indeed been a misery. He could no more master Latin grammar than he could sew a fine seam. Sweat ran off him in rivers as he struggled with ‘

mensa, mensa, mensam

’. What did it all mean?

Why not just call it a table?

he groaned. Disgrace was looming – he’d be sent back to Father, a failure.

Then, quite suddenly, everything changed. Dr Fenton pushed his books to one side and said, ‘I hear you are a fine swordsman, James?’

Bemused by the change of direction, James admitted that the Master at Arms had said he was quite good.

Dr Fenton beamed. ‘Aha, I see the modesty of a knight in you!’ James could only blush; he rather liked the reference to knighthood. Fenton went on: ‘Let’s forget the Latin, James. I just needed to know where your talents lie. I have a proposal for you. How would you like me to teach you about the great generals of Roman times: Caesar and Scipio – or Agricola, who brought the Legions to England, or Hannibal, who crossed the Alps with elephants? What d’you think, James?’

James’s jaw had dropped. ‘Oh how wonderful. But what about

Father?’

‘As we say in law, we must tell the truth, but we don’t have to tell

all

the truth. This will be our little conspiracy, eh?’

Dr Fenton knew how to fuel James’s imagination. In one lesson James would imagine himself in Roman armour leading his platoon through the sea-spray to conquer Britain, and in the next would be struggling with Hannibal in the alpine snows. On top of this was the added thrill of secrecy, not just from Father, but also from Fion and Sinéad.

About a month ago there had been a change. One day Dr Fenton moved his chair closer to James’s and lowered his voice. ‘Let’s move on from the Romans, James, because, you see, we Normans are part of history too.’ Over the next weeks his tutor gradually drew James into new and dangerous territory. ‘It was we, James, who brought civilisation from France to England after the battle of Hastings in 1066. As a result, England is civilised now – but what about Ireland?’ He fixed James with his slightly bulbous eyes. ‘When the Leinster chieftain Dermot Mac Murrough invited us to come to his aid here, there were too few of us to civilise the whole of Ireland. We failed, and became more Irish than the Irish. So, you see, what the English are doing in Ireland now is really the work that we Normans left undone five hundred years ago!’

James was stunned. It was the complete opposite to what he had been taught. ‘But – Father – Uncle Hugh – are they wrong to be fighting against England, then?’

‘Yes, my boy. They belong to the old order, but

you

belong to the new. Think of the great generals I have been telling you about – they didn’t become great by backing losers. You owe it to your

father to think for yourself.’ Again he dropped his voice. ‘Do you want to end up like Hugh O’Neill, hunted from pillar to post like an old wolf? Do you want to blunt your sword cutting ferns for your bed? One day he’ll be gone, and whose side will you be on then? With the squabbling Irish, whose only interest is to steal each other’s cows? Or will you come out to support the English and King James, whose one wish is to bring peace and prosperity to Ireland? You won’t be alone. While Sir Arthur Chichester leads the English side, you may trust him with you life.’

Just once the old rebel flared in James. ‘I can’t do this behind Father’s back!’

But Dr Fenton had a reply ready. ‘Of course, tell your father if you wish. You could always tell him in Latin.’ James quickly forgot his scruples.

And now he had murder on his mind, at least when he was half-asleep! When should he confront Father and tell him O’Neill was no longer welcome? That the Earl of Tyrone was a loser? Fenton would know.

James set out for his tutor’s house, weaving through the small town of thatched buildings that crowded about the castle tower. There were workshops – a forge, an armoury, a shoemaker – barns and stalls, not to mention the cottages and houses for castle staff and labourers on the farm. Closest to the keep were the kitchens, separate from the castle for fear of fire. Dr Fenton’s house was just beyond the kitchens. ‘Close to his dinner!’ Sinéad had commented,

eyeing their new tutor’s bulging gown.

Dr Fenton always insisted that James come to his house only at lesson time, but James desperately needed his advice now. He knocked. No reply. Fenton wouldn’t want him hovering outside, so he lifted the latch and stepped inside. The room was dark except for a widening wedge of light at the back. The tutor was opening the back door to someone else’s knock. James could see him in silhouette, and beyond him a face James recognised: the pig-swill man.

What on earth could Fenton want with the pig-swill man?

Now he heard the pig-man’s voice. ‘They’re coming, Master!’

‘Good!’ Dr Fenton started to close the door.

‘A shilling, your worship. You promised!’

A shilling! Is Fenton buying a whole herd of pigs?

James wondered.

There was a brief argument, then the door closed and Dr Fenton turned into the room, smiling broadly and rubbing his hands. He saw James and started. ‘Good heavens, James! Did you hear – no, it doesn’t matter – you wouldn’t understand. Why this sudden visit?’

‘I’ve come to tell you, I’m going to tell Father that Uncle Hugh is no longer welcome here. It’s time I stood up and–’ He saw Fenton’s face change from irritation to dismay, and stopped.

‘James, dear boy, this is

not

the moment, truly it isn’t. You see, I’ve just – you could ruin everything. Believe me, this is the very moment when we must make the Earl of Tyrone very welcome indeed. Great things are afoot.’

James, irritated, started to walk up and down. What was going on?

Dr Fenton seized him by the elbow. ‘Calm yourself, James. You are like David looking for Goliath.’ He had an idea. ‘Why don’t you practise on young Fion instead of the Earl? A little rough and

tumble won’t harm him. He is the Earl’s nephew, after all. But you must go; I have business to attend to,’ and he almost pushed James out the door.

Damn it

, thought James angrily,

he’s treating me like a child. But I’ll have it out with Fion. He’s had it coming to him

.