Front Court Hex (2 page)

Authors: Matt Christopher

“Okay, Jerry, take Manny’s place,” Coach Stull said.

Jerry reported to the scorekeeper and went in when a jump ball was called between Lin Foo and a Foxfire guard. Manny Lucas,

the sub, went out. Although his man had scored five points against him and none against Jerry, Manny looked disappointed that

the coach yanked him.

Lin got the tap off to Chuck Metz, who quickly passed to Freddie. Freddie dribbled downcourt, stopped as he was double-teamed,

and drew a whistle when he dragged his pivot foot. He glared at the ref, but gave the ball up without saying a word.

The Foxfires took it out, and in three passes scored a basket to put them eight points ahead.

“Jerry, get in there!” Coach Stull shouted from the sideline.

Jerry frowned at him.

Get in there? I can’t be all over the place at once, Coach!

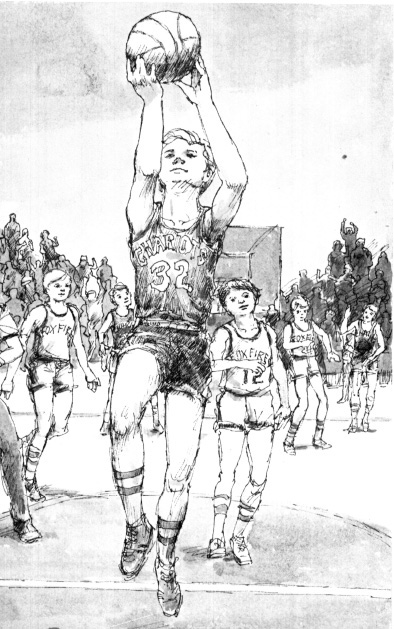

He succeeded in pulling down a rebound after a miss under the Chariot basket, and brought the ball upcourt. A Foxfire sneaked

up unexpectedly beside him and smacked the ball out of his hand. Jerry exploded into fast action, bolting after the ball to

get it back. His charge knocked down the Foxfire. A whistle shrilled, and Freddie Pearse yelled, “Watch it, Jerry! This isn’t

a football game!”

The Foxfire was given a free throw, and sank it. Foxfires 22, Chariots 13.

Still glum over his carelessness, Jerry tossed the ball from out-of-bounds to Ronnie and froze on the spot as he saw a

scarlet uniform sweep in front of the redheaded forward, snare the pass, and dribble it downcourt.

“Jerry!” a voice yelled disgustedly, and Jerry realized that someone else had now joined forces against him — Ronnie Malone,

his best friend.

For an instant they stared at each other. Then they moved together, sprinting after the dribbler.

“Didn’t you see him coming?” Ronnie asked.

“I wouldn’t have thrown it to you if I had, would I?” Jerry answered.

“Stop arguing out there and go after that ball!” Coach Stull’s voice boomed.

The Foxfire was stopped by Lin Foo, who nearly stole the ball back from him. The Foxfire passed to a teammate. The teammate

faked a shot, then lost the

ball to Jerry, who knocked it out of his hands. Jerry dribbled the ball back up-court. Finding himself all alone as he crossed

the center line, he sped on to the basket, feeling certain that he couldn’t miss now.

He leaped, laid the ball against the boards and feeling sure of himself, ran onto the stage without waiting to see if the

ball sank into the net. At the same time a yell rose from the Chariot fans, telling him that he had finally —

Suddenly the yell changed to a surprised groan!

Oh, no!

Jerry thought.

He saw Foxfires and Chariots running in toward the basket, and knew that the easy lay-up shot had missed.

It’s impossible!

he thought.

That shot was perfect!

The horn blew, ending the first half.

I

DON’T KNOW, RONNIE,” Jerry said. “Something’s sure funny about my missing the basket every time. I

feel

it.”

Jerry and Ronnie were in the locker room, near a corner where they couldn’t be overheard. The other players sat by themselves,

resting for the start of the second half.

“You’re just off,” Ronnie said. “Anybody could be off sometime. Even me.”

He laughed, and Jerry knew that Ronnie was only trying to make him feel better. But not even a good joke could shake

him loose from what bothered him now.

“Maybe you’re being jinxed,” Ronnie said, and laughed again.

Jerry looked at him seriously. “You know — that’s exactly how I feel.”

“Yeah. Me, too,” said Ronnie, and started to walk away.

“Hey! Where are you going?”

“To comb my hair,” replied Ronnie.

Jerry watched him open a locker and start combing his hair as he stood in front of a small mirror fastened to the inside of

the locker door.

“Red is beautiful,” Freddie Pearse said, and a chorus of laughter erupted from the boys. It didn’t bother Ronnie, who kept

on combing his hair as if he hadn’t heard a word.

A few minutes later Coach Stull talked to them, advising them about “better man-

to-man defense” and getting “closer to the basket before you shoot,” then ordered them upstairs. After both teams had their

warm-ups, the second half began. Jerry was surprised that he was starting. Apparently the coach had approved of his performance

during the first half.

The first two minutes went by scoreless, neither team approaching its basket close enough to chance a shot. Then Jerry suddenly

cut loose, breaking for the basket after a quick pass from Ronnie.

But he didn’t shoot. He wasn’t going to risk missing a basket again no matter how easy a shot he had. He saw Freddie break

away from his guard, and bounced the ball to him. Freddie caught it, went up and sank it for two points.

“Nice play, Jerry!” yelled his favorite fan, his father.

“I’ll go along with that,” Freddie laughed as they ran back up the court.

“With what?” Jerry asked.

“With that ‘nice play’ stuff. As long as you don’t shoot, you do okay.”

“Thanks,” said Jerry coolly. Even if he failed with his shots he didn’t intend to give up trying altogether. He enjoyed shooting.

Scoring points now and then builds up a guy’s confidence. It helped the team to win, too.

Jerry kept close guard of his man as the Foxfires moved the ball upcourt. Just over the center line Ronnie pressed the ball

handler, forcing him to pass. The throw was poor, and Lin Foo intercepted it, rushing downcourt as fast as he could dribble.

Ronnie and a Foxfire ran with him, one on either side. As the Foxfire threatened to stop Lin, the boy flipped

the ball to Ronnie. In one sweeping motion, Ronnie caught the pass, jumped and laid it in for two points. Foxfires 22, Chariots

17.

Both coaches sent in subs, and then Freddie Pearse really got hot. He sank four baskets in succession and a foul shot for

nine points to the Foxfires’ two, making the score Foxfires 24, Chariots 26. The Chariot fans yelled their appreciation, and

Jerry saw a smile play at the corners of Freddie’s mouth.

Last season things were different. It was

he

who had sunk them one after another.

He

whom the fans had cheered. What was he doing this season that could be so wrong? Why couldn’t he even get that first basket?

You would think that something was deliberately keeping him from getting it.

Both teams fired in more baskets, and by the end of the third quarter the score was Foxfires 31, Chariots 34.

Coach Stull talked to his charges during the brief intermission, urging them to play “tight ball” during the last quarter.

“We’re in the lead so let’s keep it that way,” he said. “Make sure of your passes and don’t take any long shots. Freddie has

been shooting great this second half, so keep feeding him. If he gets double-teamed, feed Ronnie, or take a shot yourselves.

I want you to remember that too, Jerry. The Foxfires must think by now that you’re not a shooter, so fool them. Drop in a

couple. You’re due.”

Soft laughter trickled from the players as all eyes turned to Jerry. His face got hot as he found himself the center of attention.

The horn sounded, announcing the beginning of the fourth and last quarter, and Jerry found himself walking out onto the court

with Freddie.

“Sure, drop in a couple, Jerry.” The tall center laughed. “That wouldn’t fool only them. It would fool everybody!”

Jerry found himself becoming blindly angry with Freddie. He wanted to hit him, and only the knowledge that fans were watching

stopped him.

The Foxfires took the tap and moved with renewed energy, passing the ball swiftly and accurately in a zigzag pattern up the

court. The Chariots seemed dazed at what was going on and suddenly the Foxfires had scored again. 33 – 34.

Chariots’ ball. They passed it upcourt, then back and forth to each other as they tried to maneuver it closer to the basket.

Then — an interception! The Foxfires took the ball down to their end of the court and in two passes they scored again. 35

– 34! They were ahead!

“C’mon, you guys!” Freddie yelled. “Let’s stop ’em!”

They didn’t. The Foxfires dumped in more baskets, raising their score to 43. Twice Jerry had stolen the ball from a Foxfire.

Three times he had intercepted passes. But his efforts weren’t enough to stop the rolling Foxfires.

The Chariots called time, and once again Coach Stull talked to his charges. “You’re too tight, guys. You’ve got your minds

made up that they’re going to win, and you’re letting them do it. Sure you’re playing hard, but you’re going about it the

wrong way.

Think

when you’ve got the ball. Hold it for a second before you get

rid of it. You can do it. I know you can.”

They went out and began playing a different game, a better game. Their passes were accurate, their shots better timed. The

gap closed on the score. The minutes became seconds. Fifty-nine… fifty-eight… fifty-seven…

The Foxfires dumped in a shot, then the Chariots dumped in one. With fifteen seconds to go the Foxfires were leading 48 –

47. The Foxfires had the ball, passing it among themselves to kill time. Suddenly it was intercepted!

Jerry had it, his fifth steal of the game. A resounding roar exploded from the Chariot fans as he dribbled the ball upcourt,

not a single Foxfire nor Chariot near him.

“Make it yourself, Jerry!” the familiar voice of his father shouted.

He reached the basket and shot. The

ball hung on the rim a moment — then rolled off!

It seemed, as Coach Stull had said earlier, that “someone had pulled a string on it” to keep it from going in. The resounding

cries died as quickly as they had started.

Two seconds later the game was over.

F

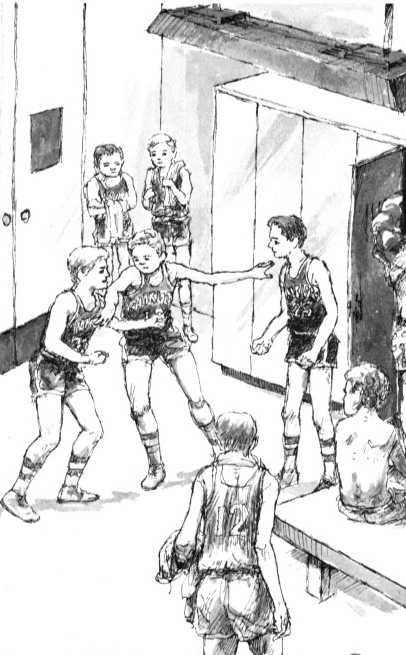

REDDIE AND JERRY almost got into a fight in the locker room.

“You stink, Jerry,” Freddie was saying. “You must be paying Coach Stull to let you play because you’re next to worthless.”

Jerry couldn’t take it any longer and barged into Freddie, fists clenched. But Ronnie jumped between them.

“No, Jerry! No!”

An ache lodged in Jerry’s throat as he looked at Ronnie, then at the glowering

face beyond. Freddie’s jaw stuck out, and his fists were clenched, too.

Coach Stull stepped into the locker room. His black eyes flashed. “What’s going on here?” he demanded.

“Nothing,” said Ronnie. “Everything’s okay now, Coach.”

The coach looked at Freddie and Jerry, then at the others. “Take your showers, then get out of here. And don’t put the blame

for our loss on anyone. You each played an excellent game. Winning’s fine, but losing is no disgrace. See you tomorrow.”

Fifteen minutes later Jerry finished dressing and looked for Ronnie.

“He’s gone,” said Lin Foo, zipping up his jacket. “Left about five minutes ago.”

Jerry headed for the door, an ache in his stomach. He didn’t care if Freddie Pearse

never spoke to him again, but it was different with Ronnie. Ronnie had always been a good friend, a buddy. They rode bikes

together, worked for the same merit badges together, shared each other’s secrets. Without Ronnie he had no one.

Oh, sure, there were Mom and Dad, but they were different. The three of them went on picnics together, to movies and to vacation

spots in the mountains. But that wasn’t like being with a kid your age, a kid who enjoyed doing the same things you did.

Lin Foo walked with him most of the way home, then turned off on another street. “G’night, Jerry. See you tomorrow.”

“Good night, Lin.”

Snow flurries whipped about like tiny white feathers, striking Jerry’s cheeks and melting almost instantly. A car’s head

lights pierced the darkness. Jerry waited till the car passed by, then started to cross the street when somebody called his

name. He paused and looked down the street. A kid was running toward him, a kid slightly shorter than he.

Jerry stepped back onto the curb and waited for him. He frowned as the figure drew closer.

“Hi, Jerry. I’m Danny Weatherspoon,” the kid said. “I — I’d like to talk to you a minute.”