From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (23 page)

Read From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 Online

Authors: George C. Herring

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #Geopolitics, #Oxford History of the United States, #Retail, #American History, #History

Clay's high-stakes gamble paid off handsomely. In the last months of 1814, the U.S. position changed dramatically. In one of the most significant battles of the war, U.S. Navy forces under Capt. Thomas Macdonough destroyed an enemy fleet on Lake Champlain (September 11, 1814), giving the United States control of the lake and thwarting Britain's northeastern campaign. The British expedition into the Chesapeake Bay enjoyed initial success. Militia defending the makeshift capital at Bladensburg ran so fast they could not be captured. British forces entered and burned Washington, one of the most humiliating events in the nation's history.

83

The looting was left to American hooligans. But while poet Francis Scott Key watched and pondered and wrote what would later become the national anthem, a British attack on the vital commercial city of Baltimore was repulsed. The invaders retreated to their ships.

Luck once more smiled on the United States. The imminent breakdown of peace negotiations at Vienna and political turmoil in France threatened resumption of the European War. Faced with abandoning its inflated war aims in America or fighting an extended and costly war in which, according to the prime minister, Britain was "not likely to attain any glory or renown at all commensurate to the inconvenience it will occasion," London chose the better part of valor.

84

The negotiators signed a treaty on Christmas Eve. The next day they celebrated with beef, plum pudding, and toasts to the unlikely duo of George III and James Madison.

Dismissed as the "Treaty of Omissions" by a cynical French diplomat, the peace of Ghent accurately reflected the stalemate on the battlefield. It said nothing about impressment and other issues over which the United States had gone to war. Britain scrapped its vindictive and expansive war

aims for the

status quo ante bellum

. The treaty fixed the northern boundary of the United States from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains at the 49th parallel and referred the disputed northeastern boundary to arbitration. The U.S. delegation was itself bitterly divided on British demands regarding the Mississippi River and fisheries. The New Englander Adams was willing to trade British access to the Mississippi for the fisheries; Clay vehemently opposed sacrificing western interests. Not for the first time mediating among his contentious colleagues, the Swiss-born Gallatin proposed deferring these issues for future discussion, a wise decision as it turned out. The British went along.

Despite its inconclusive outcome, the War of 1812 had a huge impact on the future of North America. The United States had gone to war in 1812—as in 1775—confident of the dubious loyalty of British North Americans and even hopeful they might rally to appeals to throw off British "tyranny and oppression." Ironically, U.S. efforts to relieve Britain of its provinces and the bitter fighting along the border helped stimulate in Canada's disparate population a sense of cohesion and even nascent nationalism. The former Loyalists of Upper Canada, in particular, took enormous pride in repulsing the Yankee invaders, fueling an anti-Americanism that persisted into the future. The war gave Canadians a sense of their own distinct history and helped create a "national idea."

85

The War of 1812 also sealed the tragic fate of Native Americans—the ultimate losers of a stalemated conflict. The Battle of the Thames opened the Northwest for U.S. expansion. The death of Tecumseh dashed fragile dreams of an Indian confederacy. In the South, conflict between those Creeks who sought accommodation with the United States and those who chose resistance exploded in July 1813 into war. The Americans invaded the Creek nation from three directions, destroying villages and inflicting heavy losses. At Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, Andrew Jackson's militia crushed the Creeks and their Cherokee allies, killing close to a thousand braves, causing even that hardened Indian fighter to admit that "the carnage was dreadfull." In all, some three thousand Creeks were killed, 15 percent of the population. "My people are no more!" the half-breed Creek leader William Weatherford lamented.

86

In the subsequent Treaty of Fort Jackson, imposed on accommodationist Creeks over bitter objections, the Indians surrendered without any compensation twenty-five million acres, roughly half their land, and forswore any future contact with the British and Spanish. The Treaty of Ghent was to restore the

status quo ante bellum

in Indian affairs and might have been interpreted as nullifying the earlier Treaty of Fort Jackson, but in fact both were ratified the same day. As a result of the War of 1812, foreign nations would never intercede with the Indians again, depriving them of what little leverage they had. The Indians would never again threaten U.S. expansion. From this point, the United States imposed its will on them. Councils were no longer matters of sovereign nations negotiating on the basis of rough equality. By the force of events, if not of law and equity, Indians affairs became a matter of domestic policy rather than foreign relations for the United States. The War of 1812 opened the way for removal of the Indians and their destruction as a people.

87

Although the United States had achieved none of its aims and barely averted disaster, the war marked a major step in its development. With peace in Europe, the issues that had led to war lost their significance. It would be another fifty years—and with the roles reversed—before questions of neutral rights would resurface. The United States had survived a major challenge without external assistance, demonstrating to a skeptical Europe that hopes of its imminent collapse were unfounded. Henceforth, Europeans would treat the new nation with greater respect.

Probably most important was the impact on the national psyche. From 1783 to 1814, Europeans had subjected the United States to repeated indignities and challenged its existence as an independent nation. At home, Federalists questioned the validity of the government's principles and defied its authority. Many Republicans themselves began to doubt whether a government such as theirs could survive in a hostile world. The nation's demonstrated ability to withstand the test of war eased growing self doubts. Twenty-six Federalist delegates from the New England states had assembled at Hartford, Connecticut, in December 1814 to consider demands to be made to the national government. The news from Ghent and New Orleans rendered the Hartford Convention irrelevant and made it the butt of national ridicule. The Federalist party was discredited, never to recover. The Republican party emerged from the war more firmly entrenched, its prestige greatly increased. National unity was enhanced. "They are more Americans," Gallatin observed of his adopted countrymen, "they feel and act more as a nation."

88

Through that remarkable process by which memory becomes history, the repeated embarrassments

and near disaster that had marked the war were forgotten. Victories over the world's greatest power avenged old wrongs and restored national self-confidence. In particular, the decisive victory of Jackson's strange assortment of frontiersmen, pirates, free blacks, Creoles, and Indians over eight thousand seasoned British veterans in the monthlong Battle of New Orleans was seen as confirming the superiority of virtuous republican militiamen over European conscripts. Americans learned of New Orleans and the Treaty of Ghent at about the same time, and this sudden turn of events had a huge psychological impact. "Never did a country occupy more lofty ground," Massachusetts Republican and Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story exclaimed with unrestrained hyperbole. "We have stood the contest single-handed against the conqueror of Europe."

89

"What is our present situation?" Clay asked in jubilation. "Respectability and character abroad—security and confidence at home. . . . Our character and Constitution are placed on a solid basis, never to be shaken."

90

The War of 1812 thus "passed into history not as a futile and costly struggle in which the United States barely escaped dismemberment and disunion, but as a glorious triumph in which the nation had single-handedly defeated the conqueror of Napoleon and the Mistress of the Seas."

91

Now resting on a firm foundation, the United States was poised for conquest of the continent.

"Leave the Rest to Us"

The Assertive Republic, 1815–1837

During a tense exchange on January 27, 1821, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and the British minister to the United States, Stratford Canning, debated the future of North America. Emphasizing the extravagance of Britain's worldwide pretensions, Adams pointedly remarked: "I do not know what you claim nor what you do not claim. You claim India; you claim Africa; you claim—" "Perhaps," Canning sarcastically interjected, "a piece of the moon." Adams conceded he knew of no British interest in acquiring the moon, but, he went on to say, "there is not a spot on

this

habitable globe that I could affirm you do not claim." When he dismissed Britain's title to the Oregon country, implying doubts about all its holdings in North America, an alarmed Canning inquired whether the United States questioned his nation's position in Canada. No, Adams retorted. "Keep what is yours and leave the rest of the continent to us."

1

That a U.S. diplomat should address a representative of the world's most powerful nation in such tones suggests how far the United States had come since 1789 when Britain refused even to send a minister to its former colony. Adams's statement also expressed the spirit of the age and affirmed its central foreign policy objective. Through individual initiative and government action, Americans after the War of 1812 became even more assertive in foreign policy. They challenged the European commercial system and sought to break down trade barriers. Above all, they poised themselves to take control of North America and seized every opportunity to remove any obstacle. Indeed, only to the powerful British would they concede the right to "keep what is yours." They gave Spaniards, Indians, and Mexicans no such consideration.

The quest for continental empire took place in an international setting highly favorable to the United States. Through the balance-of-power

system, the Europeans maintained a precarious stability for nearly a century after Waterloo. The absence of a major war eased the threat of foreign intervention that had imperiled the very existence of the United States during its early years. Europe's imperial urge did not slacken, and from 1800 to 1878 the amount of territory under its control almost doubled.

2

But the focus shifted from the Americas to Asia and Africa. The Europeans accorded the United States a newfound, if still grudging, respect. Britain and, to a lesser extent, France clung to vague hopes of containing U.S. expansion but exerted little effort to do so. Periodic European crises distracted them from North America. The vulnerability of Canada and growing importance of U.S. raw materials and markets to Britain's industrial revolution constrained its interference. While Americans continued to fret nervously about the English menace, the Royal Navy protected the hemisphere from outside intervention, freeing the United States from alliances and a large military establishment. The nation enjoyed a rare period of "free" security in which to develop without major external threats.

3

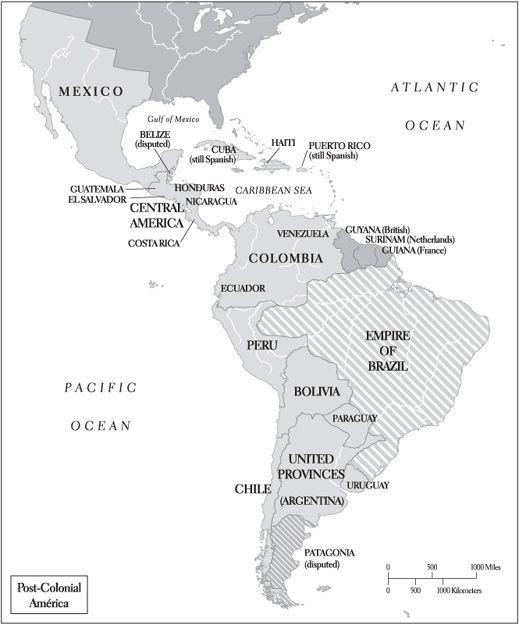

Revolutions in South America during and after the Napoleonic wars provided opportunities and posed dangers for the United States. Sentiment for independence had long simmered on the continent. When Napoleon took control of Spain and Portugal in 1808, rebellion erupted. A new republic emerged in Buenos Aires. Revolutionary leaders Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Miranda led revolts in Colombia and Venezuela, forming a short-lived republic of New Granada. After 1815, revolutions broke out in Chile, Mexico, Brazil, Gran Colombia, and Central America. Many North Americans sympathized with the revolutions. Speaker of the House Henry Clay hailed the "glorious spectacle of eighteen millions of peoples, struggling to burst their chains and to be free."

4

Some saw opportunities for a lucrative trade. Preoccupied with its own crises and eager to gain Spanish territory, the United States remained neutral, but in a way that favored the rebellious colonies. Madison and Monroe cautiously

withheld recognition. United States officials feared Spain might attempt to recover its colonies or Britain might seek to acquire them, threatening another round of European intervention.

After 1815, the United States surged to the level of a second-rank power. By 1840, much of the territory extending to the Mississippi River had been settled; the original thirteen states had doubled to twenty-six. As the result of immigration and a high birth rate—what nationalists exuberantly labeled "the American multiplication table"—a population that had doubled

between 1789 and 1815 doubled again between 1820 and 1840. Despite major depressions in 1819 and 1837, the nation experienced phenomenal economic growth. An enterprising merchant marine monopolized the coastal trade and challenged Britain's preeminence in international commerce. Wheat and corn production proliferated in the Northwest. Cotton supplanted tobacco as the South's staple crop and the nation's top export. The cotton boom resuscitated a moribund institution of slavery and added pressures for territorial expansion. Indeed, slavery and expansion merged in the prolonged political crisis over admission of Missouri to the Union in 1819—Thomas Jefferson's "fire bell in the night" that raised in a more ominous form the old threat of disunion. The crisis was resolved and disunion perhaps thwarted by the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that admitted Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state and prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Purchase territory north of 36° 30'.