Frigate Commander (28 page)

These poor fellows have suffered much from bad and short provisions and long imprisonment, they will soon come round again I hope, and God send they may gain as much credit in the

Melampus

as they earned in their old ship.

On 22 March, orders arrived for the

Melampus

to cruise for a month off the Isle de Bas (north of Ushant), to intercept vessels sailing between St Malo and Granville, for Brest. In London there was great alarm about political unrest in Ireland and Moore was aware that there was every possibility that the French might try to seize upon this opportunity by landing an army there. If they did, then the

Melampus

might be in a good position to get involved. However, he was also aware that he was cruising in the area which had been patrolled by Pellew’s and Warren’s squadrons, and he could not help lamenting their demise:

The squadron that used to be under the command of Sir John Warren seems now to be knocked up, and that under Sir Edward Pellew instead of having the range to the Westward that they had some time ago are now limited to the entrance of the Channel or the neighbourhood of Scilly. This change is generally attributed to the Jealousy and avarice of Lord Bridport who it is said remonstrated against these Squadrons of Frigates cruising in the Channel and the Bay of Biscay independent of him; it is further said that Warren laid himself open to his Lordship by running away from him at one time in spite of the signals to call him in. However this may be, Warren was put by the Admiralty under the orders of the Commander in Chief of the Channel Fleet, and soon afterwards got the command of the

Canada

of 74 guns. A squadron of frigates, some of them the same ships that Warren had with him before, have since been employed under Lord Bridport’s orders, but commanded by the Honourable Captain Stopford of the

Phaeton

, on the same ground that Warren used to be. This squadron has been very successful against the enemies privateers, and has retaken property to a very great amount belonging to the British, American and Danish merchants. Warren at present commands this squadron but under the orders of Lord Bridport in London or Bath, instead of the Admiralty.

On the last day of the month, the

Melampus

chased a lugger 100 miles, only to find out that she was a French Royalist lugger commanded by an extremely nervous English lieutenant. Moore turned back for the Isle de Bas, struggling for a week against worsening weather. When he arrived back on station he found the seas deserted and was convinced they would have no success. After a week, he noted gloomily in his diary,

I am heartily sick of this station where there appears, really nothing to be done especially without a pilot for the coast.

The only people who seemed to have any luck on this station were the infuriating Jersey privateers, who were shallow enough to operate close inshore – indeed, Moore had to watch while a number of these sailed past with their prizes in tow. Another week dragged by and Moore became increasingly despondent. At least the weather had been kind;

I hope it will continue so for the remainder of our uninteresting, flat cruise. I have no spirit to write. I have nothing to say. Is it worth while to write such stuff? . . . This has been a dull cruise . . .

[but]

the men have behaved, on the whole, well. The great body of them are well disposed although there are some Ruffians among them. I shall be extremely happy if we sail from Plymouth as strong as we go in.

It was not just the lack of activity or prizes that depressed him. A poor cruise had its effect on the crew and if they felt their commander was either unlucky or unskilled in finding prizes, they would take the next opportunity to leave the ship and find a better commander. Some commanders might try to prevent this by refusing the men leave, but Moore could not, in all conscience, deny his men the leave they deserved, and once they got their pay, they would be off. Technically it was desertion, but Moore understood the process that was going on in the men’s minds. The

Melampus

was better equipped with seamen than she had been for a long time, and Moore was dreading the return to Plymouth. On the 23rd, a cutter arrived with orders for Moore to report to Falmouth, where he was to escort the

Canada

westwards of Cape Clear. On arrival there, however, he learned that the

Canada

had sailed over a week before. Again, the

Melampus

was held up awaiting new orders, and Moore fumed quietly about the inefficiency of keeping his frigate bound in port without making use of her. Then on 31 May, urgent orders arrived. There was trouble brewing in Ireland, and he was to set sail immediately for Cork.

10

Ireland (May 1798 – November 1798)

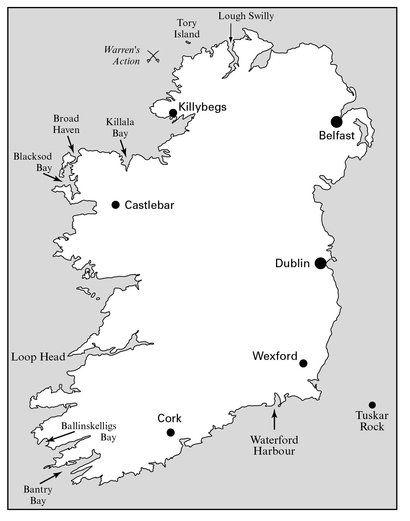

Moore’s orders were to patrol between Dublin Bay and the Tuskar Rock off the south-east corner of Ireland, to intercept any vessels attempting to land arms and supplies to rebel forces. Although he liked to keep up with politics – especially where they bore some relevance to the war – he had to admit that he was ill equipped to judge what was happening in Ireland;

There are so many extraordinary stories abroad of the designs and force of the Men called United Irish, that I can form no fixed opinion on Irish politics.

As he, and certainly the Admiralty saw it, the gravest danger lay in the French taking advantage of the situation. He was convinced that, once again, the French would attempt to land a force in Ireland but he believed they would be taking a terrible risk. An invasion force would have to be carried in a number of transports, and if a frigate or small squadron fell in with them, the only way of ‘securing’ the troops, would be to sink the transports. As a frigate commander, Moore shuddered at what he called

‘a dreadful dilemma’

, that is, being forced to choose between drowning the men by sinking the transports or letting them reach the shore.

They were off Dublin Bay on 3 June, when an Irish sloop informed them that civil war

59

had begun. Several days later the

Melampus

was joined by the frigate

Glenmore

, which had been sent by Admiral Kingsmill at Cork, also to intercept arms shipments. George Duff of the

Glenmore

was the senior Captain, and he suggested the two frigates should cruise together. The

Glenmore

was a frigate of the same class as the

Melampus

and Moore thought that she sailed

‘very well indeed’

. Duff also passed on a copy of a Dublin newspaper which carried accounts of horrific atrocities committed by the rebel Irish armies. Moore was aghast, for their actions seemed more like

. . . the furious and abominable excesses of a horde of Indians than the prepared and digested plans of a conspiracy to overset the government.

Perhaps predictably, he viewed the rebellion as an attempt to undermine the real task of defeating the French and, as a consequence, he had no sympathy for its leaders. On 5 June, the men on the two frigates saw heavy smoke inland, which could only come from a large-scale engagement. Two days later the

Ramillies

(74) joined them, commanded by Captain Bartholomew Rowley, who took them under his orders. From Rowley they learned that the smoke they had seen came from the action at New Ross where a rebel force under the Protestant, Bagenal Harvey, fought bravely but was defeated with great loss. Moore was coming to the conclusion that the loyalists would overcome this rebellion, and if the militia held true, they would also defeat any French invasion force. But it would be a hard fight, for‘. . .

their

[i.e. the rebels’]

numbers are very alarming’.

Within hours, Thomas Williams arrived in the frigate

Endymion

. He had orders to take the frigates

Melampus

,

Unicorn

and

Phoenix

under his command and patrol the coast with the direct purpose of preventing any assistance arriving for the succour of the rebel forces. It was clearly understood by the officers of the squadron that this meant a French invasion force. Moore was confident in Williams’ leadership, believing him to be

. . . an active, brave and judicious officer and I think will conduct us well if we have any thing to do. I believe on this service he would attack five or even six frigates with the three ships

c

under his orders.

As things stood on 10 June though, the wind was against anything reaching Ireland from France. Moore had become more pessimistic about the rebellion. His confidence in the ability of the militia had evaporated and he thought the government now needed to act quickly to crush the rebels before the French arrived. Ireland was clearly in widespread revolt and if experienced French troops were landed now, they would receive much better local support than they had on the previous attempt at Bantry Bay. Still, there was some optimism, for Moore had learned that his brother John had been sent to take command in the area nearby. By the 12th, the squadron was drifting on a windless sea, in thick fog. Moore could see none of the other frigates, but felt that they could not be far off. In such poor visibility it would not be possible to see a French force either, but Moore knew that Strachan’s squadron was guarding the French ports between Brest and Le Havre, and he thought it improbable any French frigates would evade them. The next day the fog lifted and, sure enough, the

Endymion

and

Unicorn

were on their station, close by. Also to be seen were English transports, hurriedly carrying more troops to Dublin

60

and over the next few days there came the sound of heavy guns from the direction of Wexford. There was no news of what was happening on land – but there was naval news. The French fleet had broken out of Toulon and Admiral Curtis’ squadron, which had been stationed off Bantry Bay on the south-west tip of Ireland, had been diverted to join St Vincent’s fleet off Cadiz in case the French should manage to join up with the Spanish fleet there. Rear Admiral Nelson was said to have sailed eastwards up the Mediterranean in the hope of meeting the French, but Moore thought that if the Toulon fleet was engaged on any expedition, it must be against Ireland. But, as yet, the wind still stood against an expeditionary force sailing from the south.

The next day the wind shifted to the south, bringing with it beautiful weather and the expected frigate

Phoenix

. The four ships hastily took up positions off the Tuskar Rock, where they were joined by the cutter

Fox

. She reported that a major battle had taken place at Vinegar Hill and loyalist forces under the command of Sir James Duff had defeated a rebel army, killing upwards of 2,000 of them. Moore noted grimly that the commander of the

Fox

had reported that

‘. . . neither side took prisoners’.

Moore could not understand the strategy of the rebels;

‘Is it choice or necessity that confined the Rebels to this part of the Country? Have they no retreat?’

Or was it because they hoped the French would land between Waterford and Wexford. Moore had to concede that in spite of

‘our zeal and vigilance’

it would still be possible for the French to throw a party of men on shore along that stretch of coast. Wishing to understand more about the rebellion, Moore borrowed some newspapers and read them carefully;

This Irish Rebellion is a most serious affair, it is difficult at this moment, to form a clear notion of it, but I am of opinion that the leaders and Promoters of it have been forced to precipitate the general rising by the late rigorous measures Government have adopted.

Yet this gave him no cause to sympathize with the rebels, for he believed that the revolutionary views of their leaders, combined with the strength of disaffection in Ireland, would make any compromise the English government offered unacceptable. Moore’s conclusion was typically pragmatic. If the rebels had to be dealt with, it was better to do it now than leave it till the winter when it would be harder for the navy to guard the coast. With equal interest he learned that his brother John had marched with part of his division against the rebels in Wexford;

Notwithstanding the danger . . .

[to]

my brother and my dearest and noblest friend, I rejoice that he is here, in the Vanguard, where the cries of their Country call her bravest sons. This is the post of the Fate of Britain.

New orders arrived with the frigate

Glenmore

on 19 June. The frigates were to move closer to Wexford to prevent any rebels escaping from there by sea. However,

. . . owing to the incorrectness of our best Charts and the ignorance of the Pilots, we were under the necessity of anchoring 8 or 9 miles from the entrance of the River of Wexford.