Friends of the Family (22 page)

Read Friends of the Family Online

Authors: Tommy Dades

Mike Vecchione receives the Distinguished Alumnus Award in Public Service from Hofstra University Law School.

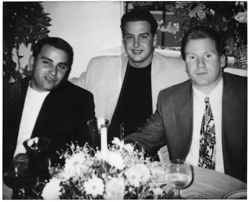

Anthony Ferrara, unknown male, and Frankie Hydell.

Courtesy of Frankie Hydell

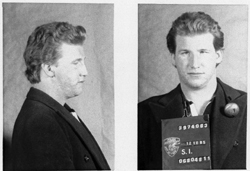

Jimmy Hydell.

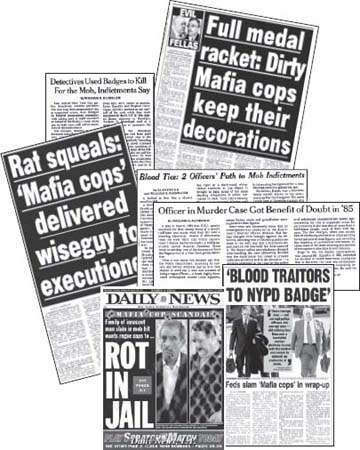

Pulled from the Headlines

Mike, Tommy, Ponzi, and Arthur Aidalia in front of the World Trade Center.

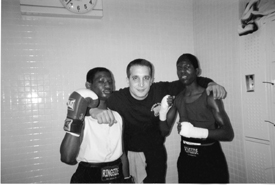

Tommy and Terance Meyers

(far left).

While there were a lot of gaps in Kaplan’s story, the big pieces fit together. He was “owned” by Furnari, who took a piece of all the business he did. In 1981, while serving three years in the federal prison camp in Allenwood for manufacturing and distributing quaaludes, Kaplan had apparently met mob associate Frank Santora Jr., who was doing time for a $12 million swindle.

When Santora found out that Kaplan knew Jimmy “the Clam” Eppolito, he offered to introduce him to the Clam’s nephew, who also happened to be his cousin, a detective named Louis Eppolito. But Louis was a very special detective, Santora told him; he and his partner had access to confidential police information and were willing “to do business on the side if the price was right.” A lot of lives were changed because Kaplan once installed an air conditioner in the Grand Mark.

According to Casso, after getting out of prison Kaplan had established a relationship with the cops. Wiseguys rarely trust cops, but this was an unusual situation. Eppolito had a pedigree. So Kaplan believed the cops could be trusted to be dishonest. The only rule was that everything had to go through Santora. Santora owned them. He carried all the requests for information, brought back the answers, delivered the money, and kept a little taste for himself. Initially it was mostly small jobs—checking out the license plates of cars seen around a social club, getting an address, looking at a report—and it didn’t involve any heavy hitting.

The situation changed considerably for Kaplan when Christy Tick went to prison in 1985 and he became the wiseguy version of a valuable free agent. Gaspipe Casso grabbed him for his crew and—always through Santora—Kaplan continued to do business as usual with the two cops he’d never met. It was a big step for Kaplan: Inside the mob Furnari was respected as a serious guy who would do whatever had to be done, while Casso was thought of more as a homicidal maniac. As Lucchese associate Anthony “Tumac” Accetturo once described Casso and underboss Vic Amuso, “They had no training, no honor. All they want to do is kill, kill, get what you can.”

Kaplan would later admit, perhaps wistfully, “Mr. Furnari would have never let me get involved in the things that Mr. Casso did.”

In early September 1987 Frankie Santora was walking along Bath Avenue

with Lucchese associate Carmine Varriale, who apparently had done something to piss off Casso. Santora was simply with the wrong wiseguy at the worst time. Three shooters caught up with them outside a dry cleaning store and killed both men. Apparently Casso did not know that Santora was Kaplan’s mysterious go-between. He once told Kaplan that if he had known about Frankie Santora’s relationship with the old man he would have been able to save him.

By then, though, the two cops were comfortable working with Kaplan. Santora’s widow arranged for them to get together. Eppolito supposedly told Kaplan, “We like working with you and Casso. You take care of business. If we tell you somebody’s cooperating you take care of it.” From that night forward Kaplan worked directly with the two cops. Although Eppolito asked many times to meet Casso, Kaplan refused to let that happen. Eppolito told him, “I’ll stand on one side of the door and he can stand on the other side.”

“That ain’t gonna happen,” Kaplan told him. The killer cops were his life insurance policy. As long as Casso needed the cops, he needed Kaplan. This relationship was a beautiful thing.

In early May 2004, as the investigation narrowed to Kaplan, Tommy began packing up his career. Once it had been a joke, “twenty and out,” but all too quickly it had become a reality. He was going out angry at the department, like a lover scorned. There were a lot of things a retired cop could do to earn, although admittedly none of them offered the excitement of one day on the job. The PAL was opening a boxing gym on Staten Island and he could run that. That was boxing, and he’d be working with kids, teaching, so that had real appeal. Several really good people he’d worked with, like Mike Galletta and Jimmy Harkins, were doing private investigations and offered him work. It was a little civil, a little criminal, mostly checking records and serving subpoenas—divorce cases, insurance fraud. A little of this, little of that; the bills would get paid.

But Vecchione and Ponzi were pushing hard to bring Dades into the Brooklyn DA’s office as an investigator. The main difference between that and being an NYPD detective was the job title. There was a hiring freeze in place, so it wasn’t easy to find a slot for him. Vecchione pushed, not just because of their friendship, but because Dades was a damn good cop and they were in the middle of the investigation of a lifetime. Ponzi pushed too,

and Hynes was completely supportive. Eventually a way was found to open a slot for him. So going out of the NYPD, he was going into the prosecutor’s office.

Officially he still had a couple of months left, but he’d accumulated vacation days and sick days and he wanted to get out as quickly as he could. It was a time for change in his life too. Ro had suggested it would be better for both of them if he moved out of the house, so he’d found a one-bedroom basement apartment. It was a new building, a nice place, and the only thing it lacked was everything that mattered to him. After years of marriage, after coming home every night to Ro and their two smart, noisy, wonderful kids, having to walk into an empty apartment every night, the only sound the electronic hum of the refrigerator, was one of the toughest things he’d ever done.

It was a bad time for Tommy Dades. His career was ending, his marriage was screwed up, and getting in touch with his father had turned out to be a big-time mistake. The man had made it obvious he didn’t want anything to do with him. The concept of a father rejecting his son was too big for Tommy to understand, so he just accepted it. He was okay with it; he couldn’t miss what he’d never had. Besides, he was still in contact with his aunt and a few other newly discovered relatives. When he would speak with his aunt they would make plans to meet, but somehow that never happened.

What he did have were the many friends he’d made on the job, and boxing. It had been almost a year since his last bout, but since then he’d been in the gym for two hours after work five days a week, hitting the heavy bag and the speed bag, jumping rope and sparring. The gym had become his real home, where he was as good as his right hand and hitting those bags again and again and again, harder, harder, let him get it out, all of it, the anger, the frustration that he kept bottled up. In the gym, he could explode.

For Tommy Dades, friends and boxing, those were the constants. And the case of the two skells.

He’d been working the case for more than a year now. He was pretty sure he knew the facts that mattered and he was still confident eventually he or somebody else would prove the two cops were guilty. But there was one thing he couldn’t figure out, one thing that just didn’t make sense to him.

Why.

Unlike the TV shows on which detectives spend just about the whole hour trying to unravel the always complicated motive behind the crime, most often the motive is pretty obvious: Money, sex, and power pretty much cover most crimes. In fact, neither Dades nor Ponzi nor Vecchione, none of these guys, ever wasted too much time wondering why a crime was committed, but this one was different. Just about every man or woman who has ever pinned on a shield, almost without exception, at one time in their career gets the opportunity to go the wrong way. The offers are there, big and small, a cup of coffee to thousands of dollars. It’s a reality of the job. To the credit of law enforcement, most of them turn it down. But having to make that decision, sometimes over and over, is an ingredient in the bond that holds them all together.

But not Louis Eppolito and Steve Caracappa. They went bad early in their careers and never looked back. If even some of these accusations were true, as Tommy Dades believed they were, then he was looking at maybe the two dirtiest cops in the whole history of law enforcement. The worst cops ever. And this time Dades, Ponzi, Vecchione, Bobby I, Le Vien, Oldham—all of them wondered why.

Louis Eppolito was easy to figure. He came from the bottom of the well. His father, Fat the Gangster, and his uncle Jimmy the Clam were made guys in the Gambino family. Jimmy Eppolito was a capo; he learned his lessons from Carlo Gambino. Louis’s father, Ralph, used to bang Louis around pretty good, trying to teach him respect and honor. Except he was supposed to honor wiseguys and respect criminal behavior. What Louis Eppolito really learned from Fat the Gangster, as he wrote in

Mafia Cops,

was the difference between the bad guys and the good guys. “My father hated cops with a passion, had no respect whatsoever for them. I guess that stemmed from the days he was buying them off for nickels and dimes.”

Growing up, Louis hung out with these guys. He spoke the language, he knew the streets. He’d even been the one to identify the bullet-riddled bodies of his uncle and his cousin, a wannabe they called Jim-Jim, after they’d been whacked. Maybe there was some time in Louis Eppolito’s life when he really had intended to join the right team, but if there had been, it didn’t last long. He was a natural.

Steve Caracappa was a little tougher to figure. It wasn’t in his genes. But by the time he joined the NYPD in 1969 he had something most cops never

get: a criminal record. Caracappa had grown up on Brooklyn’s streets and dropped out of high school at sixteen. He started working with his father as a laborer. In 1960, he and a partner were indicted on Staten Island for stealing a truckload of construction materials. Apparently the judge in the case gave him a break, reducing the charge to a misdemeanor. Caracappa pleaded guilty and was given probation. In 1966 he joined the army and served a yearlong tour in Vietnam.

Normally, a high school dropout with a record—even a sealed juvenile record—wouldn’t have been considered by the NYPD. But in the late 1960s a lot of the young men who might have applied for the job were serving in the military, and at the height of the antiwar movement it was a pretty controversial job. To fill its ranks the NYPD was forced to reduce its standards—and even then Caracappa was initially rejected. Finally though, in 1969, he was accepted.

On paper, he’d had a great career. He’d moved right up the ladder and gotten his gold shield. He’d been given important slots. Several cops who had worked with Caracappa during his career were stunned when Casso fingered him. An officer who had worked with him in narcotics defended him, saying, “On many occasions Steve put his life in danger protecting me when I was involved in making narcotics buys.” He was trusted so completely that he helped create the department’s Organized Crime Homicide Unit inside the Major Case Squad. Dades looked at his record over and over, trying to pinpoint that place, that event, when he turned. There was no easy answer. It was possible he’d been straight all the way to 1978, when he and Louis Eppolito became partners under Larry Ponzi. But even if that was true, you couldn’t blame it on Eppolito. The switch was there all the time; all he did was flip it. Dades finally decided, “I think the both of them just liked the money and enjoyed playing both sides of the fence. I don’t think they knew what side they wanted to be on. What else could it be?”

While Brooklyn and the Feds supposedly were working together in late May, U.S. Attorney Roz Mauskopf, the head of the Eastern District, called Vecchione’s boss, Joe Hynes. Mauskopf and Hynes knew each other but spoke only occasionally. They just didn’t have a lot to talk about. Although the Brooklyn DA’s office works regularly with federal investigative agencies like the DEA and postal inspectors, with rare exceptions the U.S. Attorney’s office maintained its distance from the local prosecutors. They were the

Feds; they had the full power of the government of the United States behind them. They didn’t need to make nice. Hynes had long ago accepted this situation as a reality, knowing there was nothing he could do to change it.

But Joe Hynes also knew that the Feds were armed with a much greater array of legal weapons than his office and when he believed that arsenal was needed—as, for example, in the case of Abner Louima, who was sodomized by a cop using a broomstick and who faced substantially more prison time if convicted by the Feds—he would ask the U.S. Attorney to take over the case.

Ironically, Mauskopf was calling to ask Hynes to take over a murder case. A couple of years earlier Mario Fortunato and Carmine Polito had been convicted of a RICO violation for planning a hit on Genovese family associates Sabatino Lombardi and Michael D’Urso, then attempting to fix the jury and lying to the FBI about their involvement in the crime. This wasn’t the usual kind of wiseguy hit; it was more about personal business—Polito was a piss-poor gambler who’d borrowed hundreds of thousands of dollars from Lombardi and D’Urso and wanted to wipe out his debts in two shots. Lombardi died immediately. D’Urso had been shot in the back of his head at point-blank range, but somehow he had survived.

Fortunato and D’Urso appealed their convictions, claiming that however serious their crimes and however many different crimes they may have committed, they still didn’t add up to a RICO. They were killers, not conspirators. This was a personal gripe; it had nothing to do with the family business. Incredibly, Judge Roger Miner of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals agreed. In reversing their convictions for “murder in the aid of racketeering” he wrote, “The evidence was insufficient to establish that Polito and Fortunato murdered Lombardi to ‘maintain or increase’ positions in the Genovese crime family or to establish that the shootings of Lombardi and D’Urso were related to the activities of the Genovese crime family criminal enterprise.”

There was nothing more the U.S. Attorney could do. Even if her office could figure out a way to make the RICO charge stick, retrying them would violate their protection from double jeopardy. Fortunately, being tried under the federal RICO statute does not relieve an individual of the underlying charges, in this case murder. So legally the state could try them for the murder of Fortunato and the attempted murder of D’Urso.

“I was really stunned when Hynes told me about this phone call,” Vec

chione remembers. “Here the Feds were, laying the groundwork to take the Eppolito and Caracappa case away from us to try them under RICO—and they were asking us to take a case on which they’d failed to meet the RICO standard. I couldn’t imagine they didn’t see the irony in all of this. But apparently they didn’t.”