Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream (43 page)

Read Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream Online

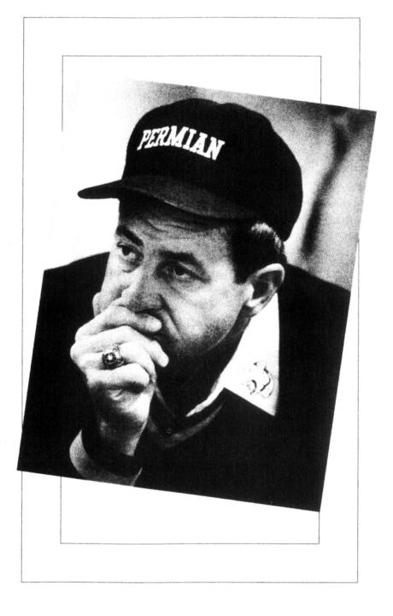

Authors: H. G. Bissinger

Tags: #State & Local, #Physical Education, #Permian High School (Odessa; Tex.) - Football, #Odessa, #Social Science, #Football - Social Aspects - Texas - Odessa, #Customs & Traditions, #Social Aspects, #Football, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Sports Stories, #Southwest (AZ; NM; OK; TX), #Education, #Football Stories, #Texas, #History

THE PERMIAN PANTHERS FINISHED THE REGULAR SEASON ON THE

first Friday night of November by pummeling the San Angelo

Bobcats. That same night, the Midland Lee Rebels finished the

season by routing the Cooper Cougars, and the Midland High

Bulldogs did likewise by beating the Abilene High Eagles. All

three teams had identical five and one records in the district,

and a numbing scenario was set up.

Since only two teams could go to the playoffs, the district's

tiebreaker rule went into effect: a coin toss.

After all that work and all those endless hours, it seemed silly.

But that's what the outcome of the season had finally been reduced to-three grown men still dressed in their coach's outfits

driving in the middle of the night to a truck stop so they could

stand together like embarrassed schoolboys and throw coins

into the air to determine whether their seasons ended at that

very moment or continued.

It was a simple process of odd man out. If there were two

tails and a heads, the one who flipped heads did not make the

playoffs. If' there were two heads and a tails, the one who

flipped tails did not make the playoffs. If they all Hipped the

same, they just did it again until someone lost.

It was hard for Gaines to find solace in any of this. But at the

very least, the place wouldn't be a complete circus. By universal

agreement among school officials, it had been decided not to disclose the location of the coin toss to the public. Doing so,

they felt, would result in a crowd of several thousand waiting

outside and a possible riot depending on who won the flip and

who lost it.

"We are not releasing the place of the meeting," Midland

school district athletic director Gil Bartosh had told the Midland

Reporter-Telegram several days before the toss. "We are fearful

that four or five thousand people might show up and we don't

need a carnival atmosphere for this. After all, some people are

going to be unhappy. There is no way around that."

As Gary Gaines drove along the dark ribbon of highway past

Bobs Creek and Fools Creek after the San Angelo game, he

knew he had no control over anything now. All he could do was

pray that God felt mercy for all souls, even those who somehow

found themselves needing it at the Convoy truck stop, where

grim-faced men in white cowboy hats picked at plates of gargantuan steak fingers as if they were picking up rocks to see

what might be buried beneath them.

To no one's surprise, Permian had just trounced the Bobcats

41-7. Winchell had thrown for 211 yards and two touchdowns, giving him a total of twenty for the season. Comer had

rushed for 135 yards to up his total to 1,221 yards. If anything,

the game simply proved how talented the team was. It gave

Permian a regular season record of eight and two, and both

losses had been by a single point each.

But it wasn't good enough without a trip to the playoffs and

everybody knew it, most of all Gaines. This hadn't been one of

those underachieving teams whose only hope was a fantastic

combination of luck and miracle. This had been a can't-miss

team, and if it didn't make the playoffs, it was scary to imagine

the enmity that thousands in town would feel for him.

Unseen, on the edges of the undulating buttes, deer and wild

turkeys stirred and every now and then the night burst alive

with a shooting star that left a delicate and misty trail. It was a

beautiful night and his car was just one of a steady stream of vehicles belonging to Permian supporters making their way

back from San Angelo like worshipers returning from a pilgrimage. They had prayed in San Angelo for a win. And now

they would go to their homes to pray that Gaines would have

the presence of mind to throw heads if it should be heads, or

tails if it should be tails.

He was in the front seat and next to him was Belew, nervously sucking one Marlboro Light after another as if they gave

him strength. They talked softly, their voices barely rising over

songs by Barbara Streisand and Neil Diamond.

A little later one of those songs from the sixties came on,

refreshingly tinny, made in a day when not all studio sound was

automatically reduced to perfect resonance.

Was it an omen? Or was it pure silliness?

"It's a song of my era, Mike," said Gaines with a laugh, and

one could imagine him back in Crane looking pretty much the

same as he did now, with those liquid eyes and melt-any-heart

smile, captaining the football and basketball teams, throwing in

the half-court shot against Fort Stockton that forever made him

a legend, winning the Babe Ruth award for being best allaround everything, distinguishing himself as one of those kids

you just knew would make their way in the world not because

they did anything with any particular flair but by the sheer will

of their own determination.

All week long Gaines had been nervous, almost snappish, but now he was surprisingly relaxed, glad to be insulated from it all

as the car spun its way toward the Midland loop.

A coin toss ...

If there wasn't so much riding on it, if hundreds of people

didn't already feel like running to the city council to get an

emergency resolution passed legalizing lynching, it would have

been laughable. But it wasn't.

Belew asked Gaines what kind of coin he was going to use, if

he had some special one imbued with magical powers. He said

he wasn't much of a gambler and talked about the time he had

stopped in Vegas on the way back from a coaches' convention

and couldn't bring himself to play blackjack.

"I was just an of country boy with my britches hangin' out,"

Gaines said to Belew with a little deprecating laugh. "I was kind

of intimidated." Instead he had played the slots and also went

to see the Siegfried and Roy magic act. He told Belew it was one

of the most incredible spectacles he had ever seen, stumbling

over his words as he described how some of the girls in the

revue hadn't worn much in the way of lingerie.

He told the story the same ingenuous way he told the one

about his trip out east when he was still at Monahans and had

gone with another coach to look at artificial-surface tracks; they

took a commuter plane from Philadelphia to Kennedy that was

so tiny it looked for a moment as though the only way to get

the other coach on board was to lasso him and throw him in the

baggage compartment..

The car went past the twinkling lights of an oil rig lit up like

it lonely Christmas tree, past the white clapboard houses of

Garden City where the town sign heralded the seven and one

record of the Garden City football team. The talk fell to snow

skiing, to money, to what it had been like when they had gone

to college, to anything but the coin toss.

They talked a little about the game, about who had played

well and who hadn't. Belew related an anecdote about a player

who had tried to quit the team earlier in the year and how his father had coaxed him hack into playing by sharing a case of

beer with him.

"I can't even begin to imagine that," said Gaines, who in his

own life could only remember disappointing his father once, in

seventh grade, when he had played a football game over in

Kermit.

His father, who worked at a natural gas plant for Gulf as a

shift supervisor, had not gone to the game that day. But he got

back reports from friends saying that his son had broken free

with the ball and then hesitated near the goal line, as if he was

scared of getting hit. In the world of a small Texas town, where

the four seasons of the year were football, basketball, track,

and baseball, there was no greater condemnation. In stony

silence later that evening, the elder Gaines sat down and ate

his supper. Few words were exchanged, few words had to

be exchanged, until he called his son into the backyard of

their home.

He told Gary that if he couldn't be any tougher, he might as

well not play. Suddenly he ordered his son into a stance and

told him to fire off and start blocking. Over and over, Gary

fired off into his father, who was much stronger than he was.

Over and over. Then he tackled his father, and then his father

tackled him. Over and over, with tears streaming down his face,

scared that his father was going to hurt him, which he never

would have, his mother listening to the painful commotion but

not daring to interfere, because this clearly was a rite of passage

between father and son.

Almost thirty years later, Gary Gaines recalled the backyard

incident in his office one day with a sheepish half-smile on his

face, describing the "bawlin' and a-squallin"' that had gone on

as he tried, without success, to tackle his father. Looking back

on it, it was the one memory of his youth he remembered above

all others, although he wasn't even sure if his father had any

recollection of it at all. But he did.

"I did it because I wanted the kid to be the best he could

possibly be and I didn't want anyone to make the remark that he was shirking his responsibilities," he said. "If he didn't put

out, he might as well not play."

If there had been a motto for Gary Gaines's life, that would

have been it. It had always gotten him through, always enabled

him to succeed, always given him a certain special edge.

Except now, as he left the serenity of the Concho Valley and

headed for the Convoy.

Gaines pulled slowly into the driveway and seemed a bit taken

aback. "Too many cars," he said. "I don't like this."

Two sheriff's cars from Midland were parked in front with

their lights off, there just in case the location of the coin toss

had leaked out and crowd control was needed. Gaines could

stomach the police cars, but he wasn't necessarily prepared for

the towering antenna rising up from the KMID-TV van.

The television station, recognizing the importance of the

event for the community, had decided to broadcast it live even

though it would not take place until after one in the morning.

The last time it had broadcast a local event live at such an hour

had been when a little girl named Jessica McClure was rescued

from an abandoned well.

Inside the Convoy, cigarette smoke mingled with fumes of

grease from the back-room grill to create a filmy substance that

hung near the ceiling like a patch of stubborn fog. Gaines

walked inside the restaurant and immediately went to the back,

past the red and yellow leather stools that ran down along the

white countertop like pieces in a checker game. He talked quietly with Wilkins, who was so miserably nervous he had become

virtually mute, and Wilkins's wife, who wore a little pin that had

a picture of their son Stan in his football jersey. At the other

end of the room, Gaines's eternal nemesis, Earl Miller, and several assistant coaches from Midland Lee sat on chairs with the

inscrutable look of Buddhas. They glanced up at their adversaries but didn't say anything.

Gaines was pale and sallow-looking. Away from the cocoon

of the car with those velvety songs and that meandering chat ter, little heads of sweat began to form on his forehead. He

fumbled with the handle of a pinball machine in the darkness

of the game room, his liquid eyes as yearning and sincere as

those of a puppy.