Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream (11 page)

Read Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream Online

Authors: H. G. Bissinger

Tags: #State & Local, #Physical Education, #Permian High School (Odessa; Tex.) - Football, #Odessa, #Social Science, #Football - Social Aspects - Texas - Odessa, #Customs & Traditions, #Social Aspects, #Football, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Sports Stories, #Southwest (AZ; NM; OK; TX), #Education, #Football Stories, #Texas, #History

He moved off the line against the Palo Duro Dons and everything was in pulsating motion, the legs thrust high, the

hips swiveling, the arms pumping, the shoulder pads clapping wildly up and down like the incessant beat of a calypso

drum.

He went for fifteen yards and it was only a scrimmage but he

wanted more, he always wanted more when he had the ball.

Near the sidelines he planted his left leg to stiff-arm a tackler.

But the leg got caught in the artificial turf and then someone

fell on the side of it and when he got up he was limping and

could barely put any pressure on it at all.

The team doctor, Weldon Butler, ran his fingers up and

down the leg, feeling for broken bones. 'then he moved to

the knee.

Boobie watched the trail of those fingers, his eyes ablaze and

his mouth slightly open. With the tiny voice of a child, he asked

Butler how serious it was, how long he would be out.

Butler just kept staring at his knee.

"You might be out six, eight weeks," he said quietly, almost in

a whisper.

Boobie jolted upright, as if he was wincing from the force of

a shock.

"Oh fuck, man!"

"We won't know until we x-ray it. It may be worse if you don't

stop moving that leg."

"You can't be serious, man! You got to be full of shit, man!"

Butler said nothing.

"Man, I know you're not talking about any six to eight weeks."

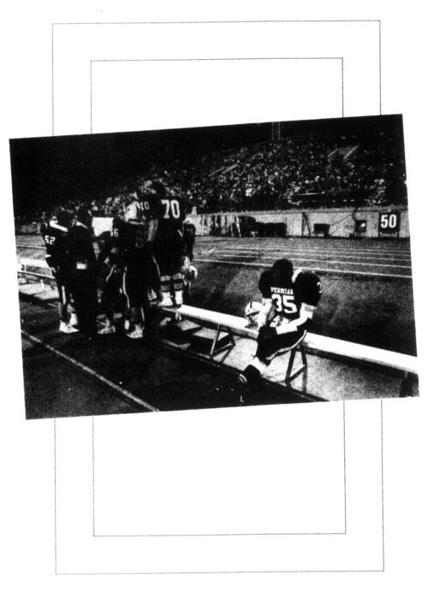

Boobie was placed on the red players' bench behind the sideline and his black high tops were slowly untied. The leg was

placed in a black bag filled with ice to help stop the swelling. He

turned to Trapper.

"Is it gonna fuck up my season, man?' he asked in a terrified

whisper.

"I sure hope not," said Trapper.

But privately, Trapper's assessment was different. As a trainer

he dealt with knee injuries all the time. His gut told him it was

something serious, an injury that might prevent Boobie from

ever playing football again the way he once had.

Boobie lay down and several student managers took off his

pads. In his uniform, with all the different pads he fancied, he

looked a little like Robo Cop. But stripped of all the accoutremerits, reduced to a gray shirt soaked with sweat, he had lost

his persona. He looked like what he was-an eighteen-year-old

kid who was scared to death.

"I won't be able to play college football, man," said Boobie in

a whisper as the sounds of the game in the gauzy light-the

hits, the whistles of the officials, the yells of the coachesfloated over him, had no effect on him anymore. "It's real

important. It's all I ever wanted to do. I want to make it in

the pros.

"All I wanted to do," he repeated again. "Make it to the pros."

When the injury occurred, L.V. could only watch with silent

horror. He had stayed frozen in the stands, not wanting to accept it or confront it, hoping that it would go away after a few

nervous moments. But there were too many people around

Boobie, looking at his knee as if it were a priceless vase with a

suddenly discovered crack that had just made it worthless.

He had always feared that Boobie would be seriously injured

one day, but not like this, not in a scrimmage that didn't count

for a single statistic, not when he was about to have it all.

He had pushed Boobie in football and prodded him and refused to let him quit. He did it because he loved him. And he

also did it because he saw in his nephew the hopes, the possibilities, the dreams that he had never had in his own life when he had been a boy growing up in West Texas, back in a tiny town

that looked like all the other tiny towns that dotted the plains

like little bottlecaps, back in the place the whites liked to call

Niggertown.

II

II

From one perspective, the quickest way to understand Crane,

Texas, was by thumbing through the ad section of the high

school yearbook. There the glossy white pages featured blurbs

for T & P Clothiers (HEADQUARTERS FOR STYLE AND VALUE!),

Crane Motor Company (SOY AND JIMMY EXHIBIT THAT HAPPINESS IS OWNING A DODGE CHARGER), Crane Flower Shop (SAY

IT WITH FLOWERS. LET IT BE OURS), Southern Union Gas Company (IF YOU WANT THE JOB DONE RIGHT, DO IT WITH GAS),

Crane Service Parts (YOUR NAPA JOBBER IS A GOOD MAN TO

KNOW) and Gloria's Salon of Beauty (BEAUTY IS OUR BUSINESS).

It was the kind of town where the big hangout was the

Dairy Mart on Sixth Street because it had curb service, where

Saturday afternoons meant plunking down a quarter for a

matinee at the movie theater on Fifth Street and Saturday

nights meant either a dance over at the county exhibition

hall or a drag or two up and down North Gaston looking for

girls and a little beer.

Fathers liked Crane because there was steady work in the oil

field. Mothers liked Crane because there were few temptations

that could entice their offspring. Children liked Crane because

they hadn't been anyplace else, except to Monahans or Marfa

or Big Lake for a basketball or football game. For many people,

it had all the comfortable fixtures and feelings of a small town.

But not everyone liked it, and L.V. Miles had been one of

those. For him, as for a handful of others who had the same

skin color, the Crane he grew up in might as well have been on

another planet.

His life had been defined by a five-foot-high wall of rock and concrete. It ran along a street and had been built so the whites

who lived on the edge of Niggertown would not have to see it.

He and the handful of other blacks who lived in this town of

thirty-eight hundred people could do whatever they wanted inside that wall; no one really cared. But whenever they ventured

outside it, it was without welcome.

He had grown up in a place where the only way he could go

into a restaurant, if at all, was through the back; where he

wasn't allowed to go to high school football games unless he

climbed a light pole or snuck under a fence; where it was perfectly fine to go to the Saturday afternoon matinee as long as

he took the stairs to the right and sat in the balcony.

The only time he had ever had contact with whites was during summer league baseball, but otherwise he stayed behind the

concrete wall that fenced him and his friends in like cattle. He

went to the colored school over on the corner. He swam at the

colored swimming pool, not the white one where the teenage

lifeguards had been placed on strict orders by a county commissioner to shut it down if any "nigger" tried so much as to

stick his big toe into it. He played at the colored park, not too

far from the spot where the cross had been burned when he

was twelve. He went to the colored youth hall.

At Bethune, the colored high school he went to,,all the tenth,

eleventh, and twelfth graders-about twenty of them-were

housed in the same little room near the entrance. He played

basketball in a gymnasium that was tiny and suffocating, and

he would never forget the one time he was allowed to play in

the gym at the white school, Crane High, and how dazzled he

was by the beauty of its backboards, by the sweet rows of bleachers rising above the smooth, glistening floor, as impossibly huge

to him as a big-city arena.

When he went back to Crane one day more than twenty years

after he had left it, it was easy to pick out the landmarks of

his life because most of them were still there-the wall that

had crumbled in places but was too well built to have disintegrated; the low-slung red brick of Bethune, with its row of grim windows like expressionless eyes; the red brick of the

movie theater on Fifth, where he had had to sit in the balcony;

the black cemetery where his mother was buried, an unadorned

piece of ground with no trees to shield it from the constant

clatter of supply trucks heading to McCamey or Texon or

some other oil town outpost, next to a sign advertising the

South Forty MX and ATV Track three-quarters of a mile (town

the road.

As L.V. Miles drove through the streets of Crane, memories

of the cross-burning and the colored pool and the wall that the

whites built bubbled to the surface. They came out at random,

with no special significance attached to one or the other, and

he talked about them neither with bitterness nor with self-pity.

That was just the way things were back then, and Crane had

been no exception.

But there was one memory that did seem to stand out above

the rest, that he remembered in more detail than the others. It

had to do with the one aspect of life that had kept him going

while he lived there, which was sports. In 1961 and 1962 the

basketball team at Bethune was the Class B state champion of

Texas for "colored" schools, running a fast break so fast and

fluid that it had the white folks in town actually setting foot in

Niggertown to see it. L.V. had been on that team. He was a

nice-sized kid back then, six feet and 230 pounds, and there

was one thing he wanted to do more than anything else. He

wanted with all his heart to play high school football.

But that was impossible. Bethune didn't have a football prograin. Only Crane High did, and L.V., who graduated from

high school in 1963, wasn't allowed to go there.

Instead the best his younger brother James and he could do

was watch the Crane Golden Cranes as they went against Monahans and Marla and Alpine and Big Lake and other West Texas

towns for whom the game of football had become a badge of

courage. The two of them snickered as they watched, knowing

they could do it much better than the bunch of white kids out

there on the field who didn't seem very tough or very fast. But. inside they bled, wanting so badly to be a part of it, to hear the

swell of an entire town that had turned out on a Friday night to

rejoice and agonize with the Golden Cranes, except, of course,

for those who lived behind the wall of Niggertown and weren't

welcome.

"You'd watch these kids play, and it seem like somethin' burning would be inside of you and want to come out," said James

Miles, remembering what it felt like to be deprived of the most

important rite of male teenage passage there was in the state of

Texas. L.V. felt the same sense of helpless frustration.