French Lessons (10 page)

Authors: Ellen Sussman

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Romance, #Contemporary, #Literary

“What happened?”

Josie looks at him, puzzled. “Oh, not much. I spent a year or two like that. And then I missed my father. All at once. I applied for every teaching job within a hundred miles of home. And I ended up in Marin. I never told him I came home to be with him.”

“Why not?”

“Because once I got there, I rarely saw him.”

Josie thought of her dad’s last visit. They never talked about Simon again. They ate pasta and salad, they drank their wine in silence. After a while, he told a long story about two boys who tried to rob the grocery store but they got in a fight in the middle of the robbery. One boy punched the other, and they chased each other out of the store. Josie told her dad to sell the place; maybe Palm Springs was a good idea. It was so simple, sitting and sharing dinner with her father. When he got up to leave she said, “I’ll come down next weekend.” His face lit up.

And then Simon died. She called her father and told him she was sick in bed and couldn’t travel.

“I’m tired of talking,” Josie says to Nico, but she keeps her arm tucked around his. “Tell me about the woman you love. The other tutor.”

“Did I mention her?”

“You did. You sleep with her but not with her boyfriend.”

“Hmm. I must have had too much to drink at lunch.”

“What is her name?”

“Chantal.”

“A pretty name.”

“A pretty woman. I only slept with her once. Though she’s in my mind many nights when I go to bed.”

“We imagine love so easily.”

“Yes. That is the simple part.”

“Does she love you?”

“She has a boyfriend, remember.”

“Does she love her boyfriend?”

“I can’t imagine. But then I don’t understand women very well. He has a reputation of sorts. He’s been known to sleep with his students.”

“Not you,” Josie says, smiling. “You wouldn’t do a thing like that.”

“I would not get so lucky,” Nico says.

“But you were lucky enough to sleep with his girlfriend.”

“Yes. Last week we all went out for a few drinks after work.”

“You’ll do that tonight?”

“Tonight I’m taking a train to Provence.”

“Of course.”

A

bateau-mouche

glides by on the river and they hear the loudspeaker barking out indecipherable words. They both turn to look. The tourists all seem to be looking at them: a couple strolling along the Seine. It should have been Simon, she thinks. She takes her hand away from Nico’s elbow and tucks her hands in her pockets.

“That night …” she says, prompting him. The boat passes by and they continue walking.

“That night Philippe was flirting with a girl at the café. She was sitting at a table nearby, with her dog at her feet, and he kept walking over and petting the dog. Finally he invited the girl to join us. For me, he said. So I wouldn’t be so lonely. The girl and her dog moved to our table. I knew that Chantal was unhappy with Philippe; she is often unhappy with him. But she usually goes home with him at the end of each evening. I don’t understand her.”

“But you love her.”

“Oh, I don’t know if I love her. She’s beautiful in a very serious way. Not like you.”

“I’m beautiful in a silly way.”

“Not at all. Even now, you have something so alive in you.”

“Even now.”

“You will come through this.”

“You’re very kind. And you’re off the subject. Chantal.”

“Yes,” Nico says. “Chantal was angry. She doesn’t show her emotions very easily. But I watch her face and I see how it changes.”

“I like you, Nico.”

He stops walking and looks at Josie.

“No kissing,” she says. “Keep walking and keep talking.”

“Chantal doesn’t like dogs. The girl’s little dog climbed up on Philippe’s lap and sat there looking very smug.”

“And the girl?”

“She was loud. She told a bawdy story about getting a lap dance from a stripper in a club the night before. Philippe asked her if she likes girls, and she said she likes girls and boys and foreigners. She especially likes foreigners.”

“Charming.”

“Chantal asked me to walk her home. Philippe was supposed to say no, that he would take her. Philippe was too busy having his fingers licked by the awful dog.”

“You walked her home.”

“I walked her right into bed. It was revenge sex. But when we were done Chantal asked me not to tell Philippe.”

“So why did she sleep with you?”

“To prove that she didn’t care about the girl and her dog.”

“Does she know that you love her?”

“No—yes. I don’t know what I feel. How could she know what I feel?”

“Sometimes women are better at this than men.”

“True,” Nico says. “If I meet her for a drink tonight she’ll tell me if I love her. But if I go with you to Provence, I’ll never know.”

“You deserve love,” Josie tells him.

Nico looks at her and she sees that his face is open with hope.

“Look,” Josie says, pointing ahead. “The film shoot that the hairstylist told us about.”

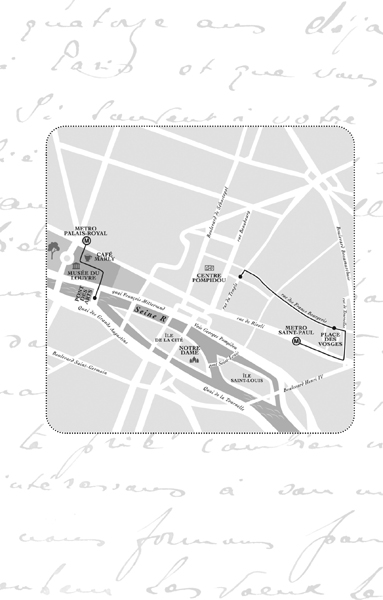

They can see a mass of people ahead, spread across both sides of the river. On the Pont des Arts, an iron pedestrian bridge that crosses the Seine from the Institut Français on the Left Bank to the Louvre on the Right Bank, there are cameras and lights and a couple of tents set up at the far side.

“Let’s go watch,” Josie tells him, her voice excited.

“Why is everyone so starstruck?” Nico asks, holding back.

Josie takes his hand and pulls him forward. “Oh, come on. We need our movie stars. We need the big screen.”

“Why? Why is that any more important than this? Because it has bright lights and cameras?”

“Because it’s bigger than we are. We disappear. This day? Tomorrow it’s gone. But that—that might be a day on the Seine that happens over and over for a hundred years.”

After the funeral—with the two matching caskets—after Josie left the hundreds of students and parents and friends and relatives and drove herself home, she lowered the shades in her cottage and crawled into bed. She took a sleeping pill and sometime in the middle of a dreamless sleep, the phone rang.

Before she thought better, she reached over to her bedside table and answered it.

“You okay?” It was Whitney again. After months of silence, Whitney was back. The married boyfriend was gone.

“I can’t talk, Whitney. I’m sleeping.”

“Don’t talk. Listen.”

“I don’t want to listen.”

“This is for the better—”

“Fuck off, Whitney.”

“I don’t mean his death. That’s tragic. And his son. I can’t believe it.”

Josie hung up the phone. Her mouth was dry and there was no water left in the glass by her bed. She pushed herself up and out of bed. She was sweaty from sleeping under too many covers. She threw off her clothes and when she glanced in the mirror she saw her body, the body that Simon made love to over and over again. She turned away, found fresh pajamas, and covered herself in them.

She shuffled to the kitchen and poured a glass of water.

The window was filled with late-evening light and her father’s blue irises. She had forgotten to move them and lower the shade. She dropped into the seat and gazed at the flowers. Then behind them, through the window, she saw a deer. It looked at her and tilted its head to one side. Then it turned away, and in one graceful leap, it crossed the creek and disappeared into the woods.

I want to leave, Josie thought. I want to flee.

She walked to the phone and picked it up. She called her boss, the head of the school, at her home.

“Did you go to the funeral?” Stella asked. “There were so many people there. I didn’t see you.”

“I was there,” Josie said.

“That poor woman,” Stella muttered.

“Listen,” Josie said. “This might be bad timing. But I wanted to tell you that I won’t be back next year.”

“Let’s talk about this on Monday, Josie.”

“I have to do it now. I’ll finish up classes. But that’s it.”

“What are you planning to do?”

“I don’t know,” Josie said.

“You’ve been very distracted. Is something going on?”

Josie mumbled her goodbye and hung up.

She walked back into her bedroom. She was thankful for the darkness again. The room smelled rank. For a moment she remembered Simon’s smell and she felt an ache in her chest. She covered her face with her hand and breathed in her own sour smell instead.

She walked to her dresser and picked up an envelope. She saw the drawing of the Eiffel Tower. At the top of the tower she saw two tiny figures. One had long hair; the other was very tall, with two green dots for eyes. She touched his mouth with her finger.

She opened the envelope. In two and a half weeks she would go to Paris. She didn’t know what would happen after that. But for now, she had Paris to get her through her days.

Josie and Nico finally find a spot from which to watch the film shoot. Nico has led her to the top deck of a floating restaurant on the edge of the quai. It’s a long boat, with beautiful teak floors and deck chairs and white umbrellas. There’s a bar at the far end of the boat, crowded with people, all with drinks in hand. Josie and Nico squeeze past the crowd and lean against the railing with an unobstructed view of the bridge.

Next to them, a waiter has opened a bottle of champagne as if this were a premiere or a national event of great importance. He pours champagne, and the group—young office workers, perhaps, all escaping work to watch the filming—clink glasses.

“I’m not convinced that this is art that will last for a hundred years,” Nico says.

A bed sits in the middle of the Pont des Arts. It’s just a bed—a frame and mattress, thrown onto the wooden deck of the pedestrian bridge. A naked woman sprawls across the bed, on a rose-colored sheet. She’s young and beautiful, and the enormous crowd on both sides of the river seems caught in a kind of reverential silence.

“Stop being a grump,” Josie whispers. They are pressed together against the rail of the boat. “Isn’t that Pascale Duclaux?” She points to a woman with a wild mess of red hair, perched in a chair at the edge of the set. “She’s a very serious director. This may very well be great art.”

“A bed on a bridge? A naked nymph?”

“And a man,” Josie says. “Check out the old man.”

A gray-haired man, also naked, circles the bed, his eye on the lovely girl. Dana Hurley, the American actress, stands at the edge of the bridge, her back against the rail, watching them. Unlike the other two, she’s fully dressed. The man doesn’t seem to notice her.

Then the man stops for a moment, his penis wagging between his legs, and he looks up, as if searching for something. He seems to catch Josie’s eye and he holds it, a half smile on his face.

He’s no older than Simon, Josie thinks. So why does it bother me so much that he’s stalking this girl?

She looks away, breaking his stare. When she looks back, he resumes his awful walk, around the bed, as if roping the girl in.

The skies rumble and, in an instant, rain pours down. This part of the boat isn’t covered—everyone turns and pushes back, under the white umbrellas or down below, under the deck. Josie stands there, watching the bridge, the bed, the girl, the man.

“Come on,” Nico says. “This is crazy.”

“Go ahead,” she tells him. “I want to watch.”

“There’s nothing to watch. They’re going to wait for the rain to stop.”

But the director signals for the cameras to keep rolling.

Josie keeps her eye on Dana Hurley. Dana doesn’t run. She’s already soaked, her hair matted to her head. She walks toward the bed as if she doesn’t have a care in the world. She won’t lose her man to a young girl. She won’t lose anyone to cancer or plane crashes. If something terrible happens the director will call “Cut!” and Dana will saunter back to her tent, where a fawning assistant will bring her a towel and a glass of champagne.

Josie realizes that Nico is right: This is not great art—this has nothing in it that will last longer than a day. The only thing that lasts is love, even when it’s gone.

“Please,” Nico says. “Come inside.”

She turns to him. He is the nicest man she has ever met. For a moment she feels unburdened by grief. Even the sound of his voice offers something like hope. Yet she can’t go to Provence with him. They are writing an ending to their own movie, a fairy-tale ending, and she no longer believes in fairy tales.

“I need to go back to my hotel,” she tells him.

“Now?”

“I’ll pack my bags,” she lies. It is so much easier than saying goodbye. “I’ll meet you at the train station at six.”

His face lights up. Thunder crashes and, in an instant, lightning blasts through the gray skies and all of Paris shines in its glow.