Freedom's Children (2 page)

Read Freedom's Children Online

Authors: Ellen S. Levine

This book is not a traditional history of the civil rights movement. Rather it is a collection of individual histories that together create a larger picture. Although beatings, arrests, and death were an intrinsic part of the story of the movement, these are not tales of sadness and despair. To the contrary, the young people in these pages speak of a pride, a confidence, a joy at being part of something they knew was right.

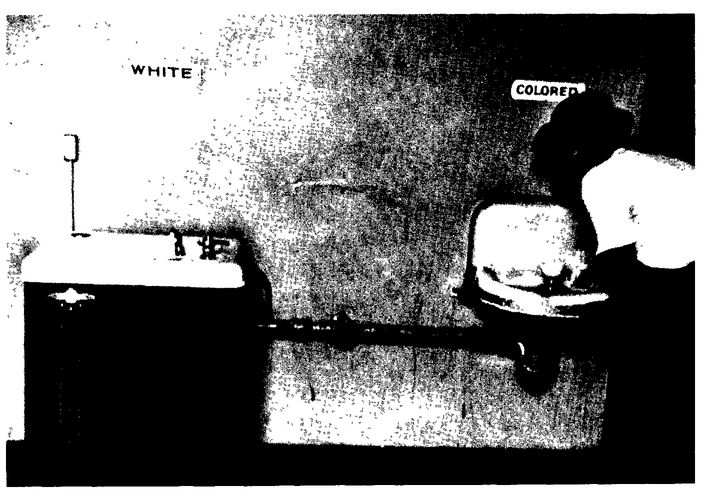

Facing page:

Separate water fountains for whites and coloreds.

Separate water fountains for whites and coloreds.

1â The Color Bar: Experiences of Segregation

Segregation was not abstract to black people living in the South; it was about everyday life. It touched every corner of southern existence imaginableâmovie theaters, hospitals, libraries, taxicabs, restaurants, schools, jobs, buses, stores, parks, water fountains, churches, cemeteries.

In one Alabama city, the public library wouldn't have children's books that showed black and white rabbits together. In another city, blacks and whites were forbidden to play checkers with each other in public places. In South Carolina, white and black cotton mill workers weren't permitted to look out the same window. In Oklahoma, telephone booths were segregated. However absurd these rules may seem today, they were meant to discriminate against and demean black people.

Some segregationists didn't stop with rules that favored whites. They supported the use of violence against blacks. Even young black children knew about the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups. They knew that blacks were beaten, arrested, terrorized, even murdered, with little or no recourse under the law. They knew that white judges often dismissed cases brought by blacks. They knew that if a case did go to trial, all-white juries rarely would convict a white for a crime against a black.

The following stories, some long, some short, recreate the segregated world as it was for young black people in the 1950s and 1960s. The children who tell their stories in this book had an immediate and palpable sense of things. They perceived the specific humiliation for exactly what it was and what was meant by it. They understood what was happening when they were given stale cookies, or sent to a separate table to eat, or heard their elders saying “Yessir” and “No sir” to white people decades younger than they were.

All of these stories reveal the extent and the meanness of bigotry. Read together, they are a patchwork of anger, humor, pain, hope, and most of all, courage.

We lived across the street from a white family. From my side of the street on, it was the black community, and from their side of the street, it was the white community. Up until the time I was about ten years old, I always played with those white kids. But once I became ten, their parents came straight out and told me they didn't want me playing with their kids no more. Their mama told them they were better than I was, and told me I couldn't associate with her son, and I had to call him “Mister.” And the kids themselves adopted that attitude.

GWENDOLYN PATTONâMONTGOMERY, ALABAMAGwen Patton grew up in Detroit, Michigan. She spent summers with relatives in Montgomery until she moved there at

age sixteen.

age sixteen.

There was this peculiar thing with my birth. About six weeks before my mother bore me, her brother was shot by the police in Montgomery, and it had civil rights overtones. My family has always felt that that incident impacted on my mother so much that I was born a civil rights worker. I was very, very independent, and I was fierce about my freedom.

I loved the South as a child. I had a whole group of friends and cousins down here. I remember one summer specifically. After Sunday school and church, my brother, my first cousin Al, and myself would ride the bus. That was a Sunday treat. We would ride for fifteen cents all the way down to the end of the line and then ride it back. I was nine and the oldest, and this particular Sunday I decided that we would stop and buy an ice-cream cone downtown.

At that time you had soda fountains, which was a big thing in my childhood. We also went to get some water. You paid three cents for this little cone-shaped paper cup, and I proceeded to sit down. This lady behind the counter told me I couldn't do that. I sensed something was wrong. She didn't call me any names or anything, but I sensed that it was because I was black. So I poured my cup of water on the counter, instructing my brother and my cousin to do likewise. The people in the store were absolutely shocked. We stormed out, got on the bus, and went home. I was outraged.

That was our first protest and boycott. When I came home and told my grandmother, she was very calm. I don't remember her at all becoming excited or lecturing or anything. But I do recall that I never was allowed to ride the bus again.

JAMES ROBERSONâBIRMINGHAM, ALABAMAMy mother wanted to leave Alabama. She could not take the hostility and the racial problems. My dad was a railroad man, and he tried to get transferred to Cincinnati. While he was waiting, my mom packed us up and we moved. I was about ten or eleven. In Cincinnati there weren't open, blatant racial differences. I talked as a black southerner, so in school I was nicknamed “Alabama.” But when I went to the board and could outdo the other kids academically, they began to accept me.

When my dad could not get transferred, we came back. On the way, the train stopped in a little town in northern Alabama called Decatur. I wanted something to eat, so I got off. I wasn't thinking about being black. I went in the front door of the train station. Suddenly everything stopped. A lady said, “Get out of here, nigger! You get out of here!” I was shocked. I ran out and got back on the train. I told my mom what had happened. She said, “Baby, you back down South.”

When that happened, it dawned on me that the lady didn't know if I was a good child, or a bad child, or a loving son, or an angel. Just because I was brown and had black hair, I could not eat there.

Â

The green sign on the Birmingham city buses was one of the most powerful pieces of wood in the city. It was about the size of a shoe box and fit into the holes on the back of the bus seats. On one side of the board it said “Colored, do not sit beyond this board.” The bus driver had the authority to move that green board in any direction he wanted to at any time.

To give you an example, the bus might be headed for College ville in North Birmingham, where blacks lived. When the maids and chauffeurs and street sweepersâthose were the jobs for blacks in those daysâwould get on the bus, they'd all be seated. In another mile, ten whites might get on. The driver would get the green board, move it, and the blacks would have to get up. A seventy-year-old black person might have to move for a six-year-old white child.

A group of us formed a little club called the Eagles. When we would get on the buses, I would take the green sign and move it up or throw it away. I was a teenager, and that was my way of fighting the system.

Sometimes we would defy the green board. We would sit right behind the bus driver. You really had to imagine the driver as a cobra snake or a vicious dog, and you're treading on his territory. You know that if you move close to him, he's going to strike you. The driver would say, “All right, you niggers got to get up.”

We'd say, “You talking to us?” There were guys who were like conductors and drove black plain cars. The bus driver would get off and call one of those guys. He would come on and say, “Get off or we're gonna call the law.”

“So call them,” we said. When he'd go to call, we'd get off the bus and disappear.

James attended Bethel Baptist Church where Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth organized some of the earliest civil rights demonstrations in the 1950s. In December 1956, a group led by Reverend Shuttlesworth was arrested for sitting in the “white” section on a Birmingham city bus. Shortly thereafter, on Christmas night, the Bethel Baptist Church parsonage was bombed. James was thirteen years old at the time.

I was home in bed. The explosion was so powerful, I thought the world was coming to an end. The vibration was enormousâif you can imagine fifty times as much thunder as you normally hear. My daddy jumped up and he ran through the house to check on us. He said, “There's been a bomb!” I ran to the front. My mother used to collect little ceramic things. The explosion had knocked all that down and everything was broken. The windows were out.

I looked across to the church. The electric wires were still flashing from the explosion. You could smell burnt rags and gunpowder. People were screaming. The parsonage had collapsed on one side. My father and Mr. Revis rushed over. Reverend was in his bedroom, which was against the outer wall of the parsonage. Between that outer wall and the church was a three-foot walkway. They had put the bomb in that walkway right next to the bedroom wall. A rafter, one of those big ones, went right through the bed. Daddy was saying he thought Reverend was dead. If he had been in that bed when the beam came through, he would have been. But the explosion had thrown Reverend out of bed.

Reverend got up and came out. He had on an old, long coat, one of those topcoats preachers wear. He did not have a mark on his body, not a drop of blood. That dynamite had blown windows out a mile or more away, but he had no deafness from the sound. He had nothing physically wrong with him. Think about it. The police said eight to eighteen sticks of dynamite went off within three feet of this man's head. He's not deaf, he's not blind, he's not crippled, he's not bleeding. That really made me think he had to be God-sent.

People had come from blocks around to see what had happened. They had sawed-off shotguns and pistols. Any white man who had gone through there probably would have been hurt. The Reverend stood in the middle of this rubble and talked about nonviolence. He said, “Go home! Put the guns away!” I never will forget him singling out one man. “You all get him and take him home. He's got a gun. We're not going to be violent. We don't want that. This is not gonna turn us around.” In the middle of that house leaning over, the sparking electric wires, the police on their way, people gathered with guns and hostility, he gave a sermon.

FRED SHUTTLESWORTH, JR.âBIRMINGHAM, ALABAMAFred Shuttlesworth, Jr. was ten years old at the time of the Christmas bombing of his home.

It was about 9:30 or 10 oâclock at night. My father was in the bedroom talking with Mr. Robinson. Usually I was sitting next to Ricky watching television, but that time I was in the dining room. I was wearing my red football uniform that I had gotten that day. All of a sudden, BOOM! It was just like a war zone.

When I saw all that dust and stuff in the air, I knew that somebody had actually tried to kill us. There was this big question mark. Why would anyone want to do something like this to me and us?

Then the fear came. I began to stutter. I didn't know why at the time. It was rough because you don't understand what is happening to you. Some folks are aggressive; some folks are passive and go into a shell. I was neither. I just stuttered every once in a while.

My uncle and aunt kept us for that year while the house was being rebuilt. He more than anybody else gave me things to read and encouraged me to express myself. I don't stutter now. But then it was the fear coming out physically.

ROY DEBERRYâHOLLY SPRINGS, MISSISSIPPII remember one incident when I was at my grandmother's. I was about five or six. She had a Singer sewing machine without the electricity. She would ask me to get down on the floor and pedal the thing for her. We were out in the yard and an old white man who was poor was coming up. My grandmother was preparing food, so it was obvious that she was going to give him some. I said, “Grandma, what does this cracker want?”

She said, “You don't do that. You don't call someone a âcracker.' This man wants some food. He's hungry.” I remember her feeding him, and that was really the first time I saw a white person come to our house for food. She also used that as an opportunity to teach me something. People are people, even though they're not always good people.

Other books

THE HOUSE AT SEA’S END by Griffiths, Elly

FourfortheShow by Cristal Ryder

Matchpoint by Elise Sax

The Bare Bum Gang and the Holy Grail by Anthony McGowan

The Devil Behind Me by Evangelene

Because of You by Maria E. Monteiro

Slipping by Y. Blak Moore

Fifty Shades of Gray: Zombie Sex Dungeon by William T. Finkelbean

PandoraHearts ~Caucus Race~, Vol. 2 by Shinobu Wakamiya

In the Stillness by Andrea Randall