Free Lunch (21 page)

Authors: David Cay Johnston

While Texas lawmakers rejected the Perry plan, California, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee, Utah,

and West Virginia are among the states that have shifted part of the cost of schooling to taxes on gambling and topless bars. In

New York, George Pataki tried when he was governor to raise money for education by making video lottery terminals more widely

available.

There is one final way that government policy discourages the poor and those of

modest means from attending college, which in the short run saves the costs of educating them, but imposes a long-term drag on

the economy. The application form for federal aid is so complicated that 1.5 million students who are eligible for aid do not even

apply.

In contrast to these trends, across most of the modern world a college education

remains so inexpensive that anyone with the necessary brains and discipline can earn initial and advanced degrees.

There was a time when college in America was free, or nearly so. But now the GI Bill and government policies

that placed the costs of education on taxpayers, a benefit extended to the next generation, have withered in the face of demands by

the wealthiest to reduce the burdens of government. As the costs of college have grown faster than inflation, and predatory lending

practices have become common, the growth in advanced education has predictably slowed. More men earned doctoral degrees in

1975 than in 2005. The total number of PhDs grew only because the number of women receiving doctorates tripled to 23,000 over

the same period. The number of bachelor's degrees earned by men grew just 18 percent during those years. The total number of

four-year degrees grew by a bit more than half because so many more women earned degrees.

In a world of growing complexity and technological demands, shortchanging higher education through rising

tuition and high-cost loans is tantamount to a policy of reducing future economic growth so that the few today can have more. It is

a kind of hidden tax on the future.

SELLING THE FURNITURE

T

HE STUDENT-LOAN BUSINESS IS JUST ONE ASPECT OF A

GREAT

transformation in the balance sheet of America. When students graduate

and start paying off their loans, many will find they cannot qualify for a mortgage to buy a home because of the money they

borrowed in school.

Home ownership used to be the key to a secure future for the middle

class, although African Americans, Hispanics, and other minorities were often excluded. Government programs after World War II

encouraged widespread home ownership and low-cost housing. No more. Now home ownership is for millions a pathway to a life

of endless debt.

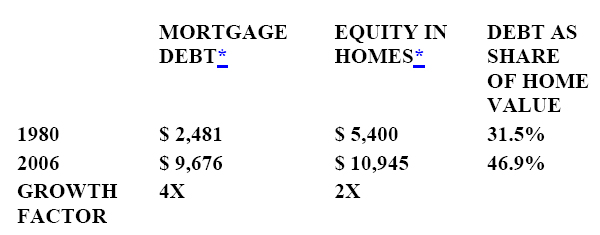

Americans owned about two-thirds of the value of their homes in the sixties

and seventies and owed the rest in mortgage debt, according to Federal Reserve data. In 1981 and 1982, for every dollar of home

value in America, equity represented 70 cents. But by 2006, the equity share of homes had fallen sharply while mortgage debt grew

to almost half the total value of American homes. In fact, for each dollar of equity people had added, they took on almost two dollars

of debt.

Debt likely accounts for more than half of the value of homes in 2008. That is because

in many communities, home values are falling, in part because the debt burdens are so high that the owners cannot cover the

payments and there are no new buyers to take over for them at current prices. Many of these mortgage loans were made to people

with poor histories of paying back their debts, and often based on inflated appraisals. The failure of subprime loans has become so

widespread that it wiped out many lenders and devoured two hedge funds sponsored by the Wall Street firm of Bear

Stearns.

MORTGAGE

DEBT GROWS TWICE AS FAST AS EQUITY

*

In billions of 2006 dollars

*

In billions of 2006 dollars

Source: Federal Reserve Flow of

Funds

These rising mortgage payments in turn have contributed

significantly to a profound change in the composition of household wealth.

From 2001 to 2004,

the median net worth of all households rose only slightly. The median measures the halfway point. Half of all households had a net

worth in 2004 of $93,100 or less, barely changed from 2001, when it was $91,700 or less. But it rose for the top half, with the greatest

growth at the very top.

Within this overall picture, though, lies a major shift in the nature of

American wealth. While the value of homes rose 22 percent from 2001 to 2004, according to the Federal Reserve, the value of

household savings and investments dropped by 23 percent.

The falloff in household savings

is reflected in the income Americans report on their tax returns. Fewer than half of taxpayers reported any interest income in 2004.

In every income bracket, the portion of taxpayers with interest income was smaller than in 1994. Among those making $10,000 to

$50,000, for example, the number of people reporting any interest income fell by a third from almost 35 million to 25 million. The

amount of interest this group received in 1994, adjusted for inflation, was more than three times what they earned in

2004.

And it was not just cash savings at the bank or credit union that declined. For every

income group earning below a million dollars, the portion of people receiving dividends from stock investments declined and so

did the amounts of those dividends.

The more people must spend on mortgage interest, the

less they can save or invest for use before retirement. That also narrows their cushion of support when the inevitable problem

comes along, from a broken transmission in the car needed for work to illness or job loss.

In

housing, current government policy also subsidizes the affluent and the rich far more than the poor and the middle class, helping

the few far more than the many. Taxpayers who make $40,000 to $50,000 per year each save on average less than $400 from the

home mortgage deduction, while those making more than $200,000 save on average more than 12 times that much, analysis of

2004 tax return data shows. Americans who make more than a million dollars a year save on average 16 times as much, nearly

$6,300 each.

For every dollar the federal government forgoes in housing tax breaks for the

poor, it spends a dollar and a half on housing subsidies for those making more than $100,000 per year, roughly the best-off tenth of

Americans.

Peter Dreier, a professor at Occidental College who studies housing patterns,

noted that “a wealthy corporate executive is more likely to receive a homeowner tax breakâand to get a much bigger oneâthan a

garment worker, a construction worker, or a schoolteacher. The current system subsidizes the rich to buy huge homes without

helping most working families buy even a small bungalow. The real estate industryâhomebuilders, Realtors, and mortgage

bankersâhas lobbied hard to preserve homeowner tax breaks, arguing that they are the linchpins of the American Dream. This is

nonsense. Only one-third of the 52 million households with incomes between $30,000 and $75,000 receive any homeowner

subsidy.”

Dreier noted that Australia and Canada do not give a tax deduction for mortgage

interest, yet they have almost the same rate of home ownership as the United States. That shows how ineffective the American

policy is. Compounding this are changes in the tax laws that result in fewer than half of homeowners getting any mortgage interest

deduction. And among even these families, a growing minority get no deduction for their property taxes because of the alternative

minimum tax, a parallel levy to the regular income tax that hits primarily at families with three or more children who own their own

home and make more than $75,000.

It is not just students and homeowners who are borrowing

in a desperate attempt to get ahead of the game. Like the widow of the profligate husband who must sell the furniture to try to make

the mortgage payment, we are almost all destined to lose the house anywayâin this case, the “house” or infrastructure we built to

support our society.

If Wall Street offers to sell you a piece of the Brooklyn Bridge, it may not

be a con. Across America, local and state governments are selling off pieces of the commonwealth. Colorado, Illinois, and Chicago

leased toll roads to private investors, with bids coming in from all around the world. Citigroup, the Carlyle Group, Goldman Sachs,

and Morgan Stanley are among those creating investment pools to acquire public assets. Their sales agents are out proposing to

take over everything from the Brooklyn Bridge to the Golden Gate Bridge, as well as parks, parking garages, water mains, and even

sewer systems.

BusinessWeek

estimates that a hundred billion dollars worth of public

assets will be sold in 2007 and 2008.

Most of the deals to sell the furniture of modern society

come with provisions exempting the investors from state taxes, while extending deductions on federal tax returns. When built,

these public assets were our common property. In private hands, though, their value can be written off by the new owners to

reduce their taxes. This erodes the tax base and shifts a burden onto everyone else.

Private

investors are not alone in looking for safe, long-term returns from owning toll roads, bridges, and other income-producing

properties. Pension funds for public workers are one of the major sources of money for these deals. Many of these deals include

tax-sharing agreements so that the tax deductions all go to the taxable investors, not pension funds and other tax-exempt

investors.

These sales of assets are typically used to provide a one-shot injection of funds for

state and local governments. Just as officials squandered most of the money from the settlements with tobacco companies, which

paid up so they could go on addicting people to nicotine, so too will the money from these sales of public assets go for

naught.

The losers in this scenario are the taxpayers who bought and paid for these facilities.

Now, more than a third of their value will be used to reduce revenues to the government, easing the burden on the wealthy

investors and adding to those of everyone else. And they will have to pay for them all over again through user charges. And those

tolls? Expect them to go up faster than government would have raised them.

Desperate as the

sale of these assets is, there are worse things. Imagine, for example, diverting assets left to help poor children just so you can add

to your own fortune. Next up, a modern mystery. But instead of a whodunit, this one is a whogotit.

16

SUFFER THE LITTLE

CHILDREN

C

ABLE NEWS

STATIONS CUT BACK ON COVERAGE OF WAR, POLITICS,

the economy, and other

issues in the summer of 2007 to make time for nonstop coverage of an heiress who cried in jail for more than two days, until a

tough law-and-order sheriff let her go.

A judge, unimpressed with photos of her carrying a

Bible and declaring her piety, sent deputies to fetch her so she could finish her sentence. Her arrest was covered live from coast to

coast, helicopters with video cameras following the squad car in which she cried all the way to the courthouse. When the

26-year-old woman finally emerged from a Los Angeles County jail, after serving half of her 45-day sentence for violating probation

in a drunk driving case, her triumphant midnight appearance was also covered live.

Paris

Hilton dressed for the occasion, wearing a smartly tailored jacket and form-fitting jeans, posing for the cameras as if she were a

model on a catwalk. In a way, she was. Hilton was modeling a new line of clothes bearing her name, the glitzmongers who play

reporters on television told viewers during endless reruns of that scene.

In all the years that

tabloid television and actual tabloids have documented every aspect of Paris Hilton's life, none examined in any serious way the

obvious question her conduct raises: What kind of family would produce someone so brazen, shameless, and self-absorbed? The

answer reveals the most audacious free lunch of all, a fortune snatched away from poor children by Paris Hilton's grandfather,

fattening his bottom line. Starving children got the leftovers.

The story begins during World

War II when Conrad Nicholson Hilton was married to Zsa Zsa Gabor, the Hungarian beauty who took nine husbands, including an

inventor of the Barbie doll. Gabor testified that Connie drove her nuts, going to mass every morning, disappearing on religious

retreats, and constantly giving money to nuns who had taken vows of poverty so they could help the poor. She said her husband

awoke from nightmares of going to hell, a not uncommon demon of rich men and women in the era before Americans began

celebrating wealth for its own sake.

“He was always giving money to the nuns,” Gabor testified

years later. “I think he was overreligious. He had a terrible guilt complex.”

Conrad Hilton would

often discuss what to do with his money on long horseback rides in the Hollywood Hills and elsewhere with his lawyer, James

Bates. Bates testified years later that his client frequently told him that his son Barron “has too damn much money.”

Conrad revised his will 32 times, gradually leaving less to Barron and more for the poor. In his last will, out of

a fortune worth more than a billion of today's dollars, he left Barron less than three million. He directed that after various modest

gifts, and his final expenses, his wealth go to a foundation bearing his name. Conrad also wrote in his will guidance to Barron and

the other foundation trustees, what he called “some cherished conclusions formed during a lifetime of observation, study and

contemplation”:

There is a nature law, a Divine Law, that obliges

you and me to relieve the suffering, the distressed and the destitute. Charity is a supreme virtue, and the real channel through

which the mercy of God is passed on to mankind. It is the virtue that unites men and inspires their noblest efforts.

“Love one another, for that is the whole law” so our fellow men deserve to be loved and

encouragedânever to be abandoned to wander alone in poverty and darkness. The practice of charity will bind usâwill bind all

men into one great brotherhood.

As the funds you will expend have come from many

places in the world, so let there be no territorial, religious, or color restrictions on your benefactions, but beware of organized,

professional charities with high-salaried executives and a heavy ratio of expense.

Be

ever watchful for the opportunity to shelter little children with the umbrella of your charity; be generous to their schools, their

hospitals and their places of worship. For, as they must bear the burden of our mistakes, so they are the innocent repositories of

our hopes for the upward progress of humanity. Give aid to their protectors and defenders, the Sisters, who devote their love and

life's work for the good of mankindâ¦.

The message of charity and hope that Conrad

Hilton wrote lost out to his oldest son's love of money. Ten days after his father died, Barron Hilton made his first move to capture

his father's fortune for himself. He did so in a way that would give him more and the poor much less.

Lawyer Bates, the other trustee of the old man's estate, fought Barron, saying he was subverting his father's

plan to deliver the maximum amount possible to the poor. “Barron Hilton does not come into this matter with clean hands,” he

argued in court papers, “and should not be allowed to defeat his father's intentions” by hiding information that would have allowed

all of Conrad Hilton's stock to go to the foundation. Bates said Barron was seeking “unjust enrichment” at the expense of

charity.

Before long Barron, at his own request, was suspended as cotrustee of his father's

estate because he had a conflict of interest. Barron was simultaneously an heir, the chairman of the board of the Conrad N. Hilton

Foundation, and chief executive of Hilton Hotels Corporation.

The issue involved a glitch in

Conrad's will. The glitch concerned how much of the Hilton Hotels Corporation could be owned in combination by Barron and by

the Hilton Foundation. A 1969 federal law limits how much of a corporation can be owned in combination by a family and its private

foundation. Congress acted in the wake of many well-documented abuses. Rich families took tax breaks, shortchanged charity,

and then stuffed the money into their own already deep pockets.

When he died in 1979,

Conrad owned almost a fourth of Hilton Hotels, Barron almost 4 percent. Together they owned more than 27 percent, while the limit

was 20 percent. To comply with the limit, Bates testified, Conrad's will gave Barron an option to buy any shares that were over the

limit, allowing him to pay for them over 10 years. The option, the will specified, was to be created at the moment the stock was

distributed from the estate to the foundation and it was conditioned on the need to sell shares because of government-imposed

limits, two facts that would become crucial.

Conrad went to his grave, Bates testified, believing

that only a small portion of his Hilton Hotel shares might be sold to Barron under the option.

Barron had a plan. Ten days after his father died he moved to exercise the option. He argued that the option

gave him the right to buy all of the shares in his father's estate, not just the number of shares needed to bring their combined

ownership down to 20 percent. There was no way to meet the limit, Barron argued, other than to let him acquire all of the shares.

However, it turned out there was a way and that Barron knew about it. So did his personal lawyer, Donald H. Hubbs. Hubbs was

also the president of the Hilton Foundation.

The way out of the 20 percent ownership limit was

to convert the foundation into a charity known as a

supporting organization.

A

supporting organization makes grants just like a private foundation, but is not subject to the 20 percent rule. The reason is that it

must give at least 30 percent of its grants to a specified list of charities. The law assumes that these charities will have an interest in

looking out for any abuses, making them less likely and, if they do occur, will report them to the government. Since Conrad directed

his foundation trustees to deliver “the greatest part of your benefactions” to Catholic nuns who serve the poor, the supporting

organization made senseâto everyone but Barron.

Barron argued that there was no way to

change the foundation into a supporting organization. However, a Texas lawyer named Thomas Broby had advised him on just

how that could be done, although the other foundation trustees were not told this. When word of this came out the other trustees

hired their own lawyers. The issue was finally presented to the Internal Revenue Service in Washington, which blessed

it.

The foundation itself has been well run under the stewardship of Conrad's grandson Steve.

It has focused its efforts, often working through Catholic nuns, on child poverty, access to clean drinking water, and preventing the

diseases that cause much of the blindness in less developed countries.

Barron's strategy to

enrich himself had a second front. He demanded that his father's shares be sold to him at a discount from the price they were

selling for on the stock market. That was extraordinary because shares of stock that convey control over a corporation usually

command a premium price. That is why, when a buyout of a company is announced, the price is usually higher than what the

shares had been trading for, often much more. The premium recognizes the greater benefits the controlling shareholder

hasâcompared to anyone who buys 100 shares from their brokerâto pay himself a salary, use company facilities, and direct its

operations.

Lawyer Bates fought back. The California attorney general joined the fight on

behalf of the poor children. For a decade, litigation ensued over Barron's plan to shortchange charity and enrich himself. Barron's

strongest argument was that while his father wanted his fortune to go to charity, he also wanted Hilton Hotels to remain in the

family. That was the reason for the option, to thwart an unfriendly takeover. Barron and his allies insisted that the old man's desire

that his “beloved Hilton Hotels” remain in the family get equal weight with his desire to help the poor.

When the case went to trial in 1986, Barron lost. The trial court judge ruled that the switch from private

foundation to supporting organization defeated the option by eliminating the 20 percent ownership limit. Barron

appealed.

Almost two years later the California Court of Appeals for the Second District

reversed the trial court's decision. The appeals court focused not on the charitable intent, so eloquently stated in the will, but on its

concern that Barron be allowed to buy his father's shares for “a reasonable and fair price that Hilton can find economically

feasible” and that would not result in an unreasonably low value to the foundation.

The

appeals court ruled that the option was created the day Conrad died. Both Myron Harpole, the lawyer for Bates, and James Cordi,

the deputy state attorney general on the case, were stunned. The will stated that the option was conditional. It was created only if

tax rules forced the sale of Hilton stock. And the option would come into existence, the will said, “at the time of the distribution” of

shares from the estate to the charity.

The appeals court had found a way to serve up a free

lunch to the rich at the expense of charity by rewriting Conrad Hilton's will. The appeals court ordered a new trial. Barron, his hand

strengthened by the appeals court, proposed a settlement. He got one.

Barron received more

than half of the value of the stock in his father's estate, about 250 times the amount specified as a gift in his father's will. In addition,

he was guaranteed an income for 20 years. It started out at about $15 million per year and has since risen to about triple

that.

And what of the stated purpose of Barron's case, that Conrad Hilton wanted the hotels

bearing the family name to remain in the family? Just eight days after his granddaughter Paris took her fashion model walk out of

jail, her grandfather Barron announced that he was selling Hilton Hotels to the Blackstone Group, a private equity fund. On top of

the hundreds of millions he has already received, he will pocket $760 million, plus increased payments from the trust, all thanks to a

free lunch served up by judges on an American court.