Freaks (24 page)

Authors: Kieran Larwood

If someone were to ask you to think of Victorian London, the picture that might pop into your head is probably that of a grand, imposing place, full of impressive stone structures like the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, the South Bank of the River Thames, and the famous Tower Bridge. You might imagine cobblestone streets with throngs of horse-drawn carriages, men in stovepipe hats, women wearing big dresses with lots of lace. Maybe there's the odd chimney sweep or ragged urchin, with a cloth cap and a cheeky grin, saying things like “Gor blimey, guv'nor” and “Up the apples and pears!”

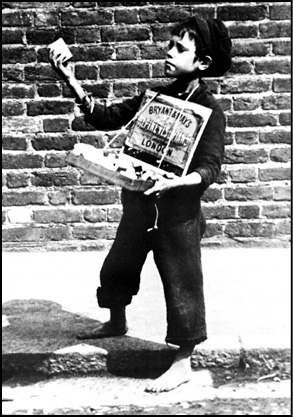

London Street Urchin

I'm British, and that's what

I

used to think, anyway.

While all those elements are actually part of the nineteenth-century monster of a city known as London, they are only a tiny part, and most of them date from the very end of the era. The term “Victorian” refers to the period of time Queen Victoria was on the throne in England: from 1837 to 1901. At sixty-three years, that clocks up as the longest reign of a British monarch in history â though our current queen, Elizabeth, looks like she's on track to break that record.

Queen Victoria (1819â1901)

So the Victorian period covers a significant amount of time, and an amazing amount of change. This was the era of the Industrial Revolution, when steam power and factories changed the world. Britain and many other countries transformed into hungry, ferocious industrial empires in the space of a few decades, and nowhere was the transformation so impactful than in cities â London, the capital of England, perhaps most of all.

At the start of Victoria's reign, London was a completely different place. By today's standards, it would rank as a third-world city, with animals in the streets, mud and grime everywhere, and the hygiene level of your brother's dirty underpants. There were no iconic buildings apart from St. Paul's Cathedral and Westminster Abbey. The banks of the River Thames were muddy and thronged with docks and buildings. The river itself was clogged with sewage and rubbish (garbage!). Even the landmark Houses of Parliament â the judicial buildings around Big Ben that are a bit like the British equivalent of the United States Congress â didn't exist. They were still being rebuilt after a fire destroyed them in 1834.

But change was underway, and by 1851, when

Freaks

is set, London was beginning its rebirth. The first train stations had begun to appear. Soon train tracks would spread across the metropolis, shoveling the slums out of their path as they went. As hordes of people poured into the city from the countryside and abroad, citizens started to worry about the stench and the disease â and they began to take steps to combat it.

Hopefully the story itself will have already given you a snapshot of what the place was like, but to give it all some historical context, here are a few facts about Victorian London.

HE

P

OOR

If you have ever read

Oliver Twist

by Charles Dickens, you might have the idea that Victorian society didn't treat its poor very well. In fact, that book is a bit of an understatement â especially since most orphans didn't have secret families of rich people running around trying to rescue them!

Had you happened to be one of the many, many unfortunate paupers in London in the mid-1800s, your life would have been miserable, uncomfortable, and disease-ridden. The only bright side is that it would have been very short.

Fifty percent of children didn't survive to see their fifth birthday. Disease was everywhere, probably because people had no idea back then what germs were, and happily drank water that was pumped straight from the river. Water that was basically raw sewage, with a little mud mixed in for flavor. Ugh.

The mudlarks in

Freaks

have a very unpleasant job, but they weren't the most unlucky. Some children went wading through the underground sewers, searching for things they could sell. Others made a living collecting dogs' droppings for the leather-tanning factories. (Once the leather had been cleaned of hair and fur, it needed to be softened. This was done by mashing it about in a mixture of animal brains, dung, and urine. The smell was delightful.) Children were also forced to sweep chimneys, work in nightmarish factories, and do many other horrible things.

London Street Children

The middle classes had just started to realize how bad things were, thanks to writers like Dickens himself. Some were trying to change the situation by proposing new laws and regulations. But life was still pretty grim if you lived in one of London's many slums.

RIME

Because of the horrible conditions, many residents of London had little choice but to try and make a living through dishonest means. The backstreets of the city were full of criminals of every description. Pickpockets, burglars, and muggers were common in the poorer areas, and there was a whole underworld of crime. It even had its own language, known as “The Cant.” Pickpockets were “dippers,” burglars were “dancers,” pistols were “barking irons.” I have put a few samples into the story, if you can spot them.

As for the law, there was a police force. In fact, there were two: one for the old city, which was and still is at the center of London, and which dates back to medieval times, and another for the greater metropolis. Police wore steel-reinforced stovepipe hats and carried wooden ratchet rattles to sound the alarm. If you were caught, the punishments were severe. Hangings were common (and very popular with spectators â literally thousands of people turned up to watch them) and the courts were very fond of “transportation,” which was basically shipping British criminals off to Australia to do hard labor. As the saying goes, out of sight and out of mind.

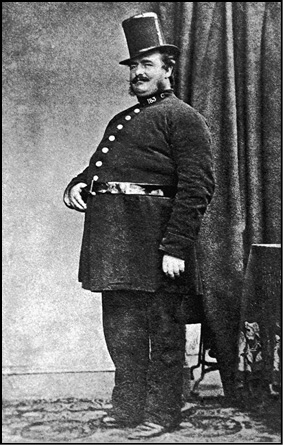

Victorian Policeman

If you weren't shipped halfway around the world to the penal colony of Australia, there were also places right there in London where you could be locked away. The most famous was Newgate Prison (known as the “Stone Jug”), but there were also huge floating prisons made from old warships moored farther down the Thames.

Despite all this, the police forces were not exactly brilliant. There was so much crime in London, they could barely make a dent. The many slum areas, such as the East End and Seven Dials, were neighborhoods best avoided. Especially at night.

REAK

S

HOWS

A city with such a huge, ever-growing population needed entertainment. And since most people were very poor, that entertainment had to be cheap.

Whilst the middle classes had their theatre, opera, and ballet, the working class had to make do with “Penny Gaffs.” These were simple stages in the back rooms of inns, packed to the rafters with audiences who had each paid a penny to enter. The shows usually featured a few acts of very poor quality, but nobody minded much, as, truth be told, they were too busy drinking gin!

Along with these establishments, there were many street performers and singers, the odd juggler or acrobat, and, of course, the freak shows.

In an age long before political correctness, people thought nothing of staring and laughing at those who didn't appear “normal.” In fact, there was a huge demand for glimpses of the unusual or bizarre. This was nothing new â so-called “freaks” had been appearing at fairs and in traveling shows since the Middle Ages â but for some reason the image of the freak show seems to have become indelibly connected with the Victorian era.

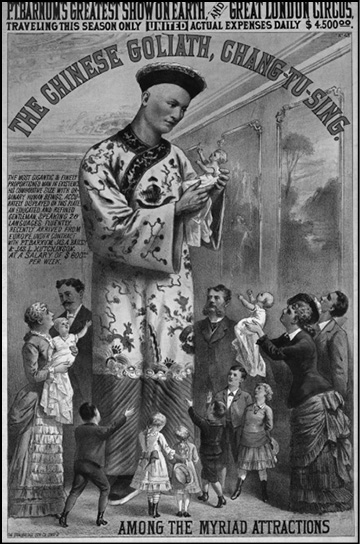

Perhaps the most famous show of the time belonged to the American P.T. Barnum. He traveled the world with his “Greatest Show on Earth,” featuring such acts as Tom Thumb and the Feejee Mermaid. Thumb even performed for Queen Victoria when Barnum visited London in 1845.

A Poster Advertising P.T. Barnum's London Show

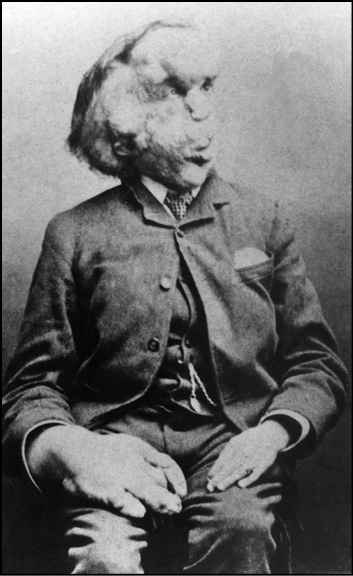

But the real reason for the association between freak shows and Victorian London is, I think, a person named Joseph Merrick. Although you might know him better as the “Elephant Man.”

Merrick is believed to have suffered from the condition now known as Proteus syndrome, which causes skin and bone to grow abnormally. His skull was covered with bony lumps, and his skin became thick and wrinkled, causing people to compare him to an elephant.