Founding Myths (5 page)

Authors: Ray Raphael

THE FULL PICTURE

The story of “Paul Revere's ride” needs not only correction or disingenuous hedging but also perspective. One hundred twenty-two people lost their lives within hours of Revere's heroics, and almost twice that number were wounded.

39

Revere's ride was not the major event that day, nor was Revere's warning so critical in triggering the bloodbath. Patriotic farmers had been preparing to oppose the British for the better part of a year. Paul Revere himself had contributed to those preparations with other important rides. After the Boston Tea Party, he rode to other seaport cities to spread the news. In May 1774, in response to the Boston Port Act, he rode to Hartford, New York, and Philadelphia to drum up support for his hometown, and that summer he spread the call for a Continental Congress. In September 1774, seven months before his most noted journey, he traveled from Boston to Philadelphia, bearing news that the Massachusetts countryside had erupted in rebellion, and the First Continental Congress, after hearing from Revere, offered its stamp of approval. That December, four months before the shots at Lexington, he instigated the first military offensive of the Revolution by riding to Portsmouth, New Hampshire. On April 7, 1775, eleven days before his most celebrated ride, he rode to Concord (which he reached that time) to warn local patriots to conceal or move their stockpiled military stores because additional troops had arrived in Boston and would soon be making their move. On April 16, with just two days to go, he traveled to Charlestown and Lexington to fine-tune preparations with local leaders, who expected the Regulars to march any day. The ride to Lexington that Longfellow chose to celebrate continued this tradition, but, as in previous rides, it took on meaning only because numerous other political activists had, like Revere, dedicated themselves to the cause.

40

Paul Revere was one among tens of thousands of patriots from Massachusetts who rose to fight the British. Most of those people lived outside of Boston, and, contrary to the traditional telling, these people were not country cousins to their urban counterparts. They were

rebels in their own right, although their story is rarely told. We have neglected them, in part, because Paul Revere's ride has achieved such fame; one man from Boston, the story goes, roused the sleeping farmers, and only then did farmers see the danger and fight back.

In truth, the country folk had aroused themselves, and they had even staged their own revolution more than half a year before (see

chapter 4

). The story of Paul Revere's ride marks the end, not the beginning, of that inspiring tale. It bridges the gap between two momentous events: the political upheaval that unseated British authority in 1774 and the outbreak of formal hostilities on April 19, 1775. But ironically, in its romanticized form, the tale has helped obscure the revolution of the people that was going on both before and after. The true story of patriotic resistance is deeper and richer than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, with his emphasis on individual heroics, ever dared to imagine.

I

n A. J. Langguth's popular book

Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution

, one patriot stands out from the rest. Samuel Adams is the instigator of every revolutionary event in Boston, while all the other patriots are merely his “recruits,” his “legions,” his “roster,” his “band.”

1

Liberty!

âthe companion volume to a PBS series on the American Revolutionâproudly proclaims, “Without Boston's Sam Adams, there might never have been an American Revolution.”

2

Children's book author Dennis Fradin makes this point even more emphatically: “During the decade before the war began, Samuel Adams was basically a one-man revolution.”

3

Samuel Adams was not always the hero we make him out to be today. “If the American Revolution was a blessing, and not a curse,” wrote John Adams, Samuel's cousin, in 1819, “the name and character of Samuel Adams ought to be preserved. A systematic course has been pursued for thirty years to run him down.”

4

From Revolutionary times to the middle of the nineteenth century, Boston's most celebrated idol was not Samuel Adams but his close friend and colleague Dr. Joseph Warren, the nation's first martyr. John Trumbull's 1786 painting currently known as

The Battle of Bunker Hill

was in fact titled

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill.

These days the eminent Dr. Warren is rarely celebrated, while we take considerable pride in our most famous mischief maker, the troublesome Mr. Adams. One modern biography is affectionately titled

Samuel Adams's Revolution, 1765â1776: With the Assistance of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, George III, and the People of Boston.

Â

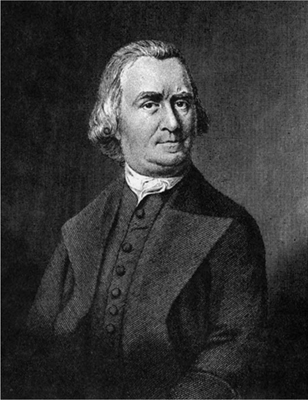

“Without Boston's Sam Adams, there might never have been an American Revolution.”

Samuel Adams.

Engraving based on

John Singleton Copley's portrait, 1772.

Â

Why the shift? In the aftermath of the War for Independence, Americans were embarrassed by any radical taint, so they did not talk kindly about notorious political activists. But with the passage of time, radicals, like gangsters, can turn into heroes. Contemporary Americans, settled and secure, need not feel threatened by stories of illegal, outlandish activities such as the destruction of shiploads of tea. Indeed, we are titillated by tales of our nation's errant youth. The Boston Tea Party elicits knowing smiles, and Sam Adams, our Revolutionary bad boy and favorite rabble-rouser, brings forth fond feelings.

Ironically, this troublemaker imbues the American Revolution with design and purpose. There are two key components to his mythic story: he advocated independence many years before anybody else dared entertain the notion, and he worked the people of Boston into a frenzy to achieve his goal. These are not incidental to our telling of the American Revolution; our view of the nation's conception leans heavily upon them. Because Adams supposedly had the foresight to envision independence, we are able to perceive the tumultuous crowd actions in pre-Revolutionary Boston as connected, coherent events pointing toward an ultimate break from England. Without this element of personal intent, the rebellion would be a mindless muddle, purely reactive, with no sense of mission. Without an author, the script becomes unwieldy; without a director, the crowd becomes unrulyâbut Sam Adams, mastermind of independence, keeps the Revolution on cue. He wrote the script, directed the cast, and staged a masterful performance.

The beauty of the story is that Adams was not some autocrat, remote and aloof from the people he directed. He was one of the crowdâone

of

us.

Perhaps that is why we like to call Samuel “Sam,” although only his enemies called him that during his lifetime. Even John Adams referred to his cousin as “Mr. Samuel Adams,” “Mr. Adams,” or by way of abbreviation, “Mr. S. Adams” or “Mr. Sam. Adams,” following the custom of the times, as in “Wm.” for “William.”

5

(In this book, “Sam” denotes the legend, “Samuel” the historical person.) Unlike many a Revolutionary patriarch, he was supposedly at home on the streets, mixing with the people, raising toasts in the taverns. How fitting that his face now adorns no coins or billsâonly a bottle of beer.

Sam Adams, who both represents and controls the crowd, allows us to celebrate “the people.” Or so it would seem. In fact, while the Sam Adams story appears to celebrate the people, it does not take them seriously. That's why the story was first invented by Adams's Tory adversaries, who wrote “the people” out of the script by placing Adamsâa single, diabolical villainâin charge of all popular unrest. To understand the damaging implications of the Sam Adams story, and to see how it distorts what really happened in Revolutionary Boston, we have to examine its genesis.

THE TORIES' TALE

Not wanting to grant legitimacy to any form of protest, conservatives in the 1760s and 1770s maintained that all the troubles in Boston were the machinations of a single individual. In the words of Peter Oliver, the Crown-appointed chief justice who was later exiled, the people themselves “were like the Mobility of all Countries, perfect Machines, wound up by any Hand who might first take the Winch.” Mindless and incapable of acting on their own, they needed a director who could “fabricate the Structure of Rebellion from a single straw.”

6

According to this mechanistic view, one man led and everyone else followed. At the outset, that master of manipulation was not Samuel Adams but James Otis Jr. According to Oliver, the mentally deranged Otis had vowed in 1761 “that if his Father was not appointed a Justice

of the superior Court, he would set the Province in a Flame.” This he proceeded to do, using the unruly yet pliable Boston rabble to fight his battle.

7

Thomas Hutchinson, the man who was chosen over James Otis Sr., told a similar tale, although less bombastically than Oliver.

8

When Otis's insanity rendered him ineffectual, the role of puppeteer was supposedly assumed by Samuel Adams, who was also motivated by family loyalty: his father had been defeated in the progressive Land Bank scheme many years before, and Samuel vowed to seek justice by deposing the regime that terminated his father's dreams. Early on, according to Oliver and Hutchinson, Adams decided to foster a revolution that would lead to independence. The Stamp Act riots in 1765, the

Liberty

riot in 1768, the resistance to occupying soldiers, the Boston Massacre in 1770, the Tea Party in 1773, and various lesser-known demonstrations were all orchestrated by Samuel Adams, master Revolutionary strategist.

“His Power over weak Minds was truly surprising,” wrote Oliver. Some of the “weak Minds” manipulated by Adams were those of lower-class Bostonians:

[H]e understood human Nature, in low life, so well, that he could turn the Minds of the great Vulgar as well as the small into any Course that he might chuse . . . & he never failed of employing his Abilities to the vilest Purposes.

But the puppets whose strings he pulled also included Boston's most illustrious patriots, people like John Hancock:

Mr. Hancock . . . was as closely attached to the hindermost Part of Mr. Adams as the Rattles are affixed to the Tail of the Rattle Snake. . . . His mind was a meer

Tabula Rasa

, & had he met with a good Artist he would have enstamped upon it such Character as would have made him a most useful Member of Society. But Mr. Adams who was restless in endeavors to disturb ye Peace of

Society, & who was ever going about seeking whom he might devour, seized upon him as his Prey, & stamped such Lessons upon his Mind, as have not as yet been erased.

9

By attributing all rebellious events first to Otis and then to Adams, disgruntled Tories like Oliver and Hutchinson exhibited the classic conservative denial of social protest: the people, if left to their own devices, will never rise up on their own. Without ringleaders, organizers, rabble-rousers, troublemakers, or outside agitators, the status quo will not be challenged because nothing is basically wrong. All protests and rebellions can be dismissed; demands and grievances need never be taken seriously.

It's easy to see why his Tory adversaries cast Samuel Adams in the leading role. Adams was a marvelous politician in every respect, equally at home in political chambers and on the Boston waterfront. An accomplished writer, he demonstrated his mastery of the art of political polemic in a steady stream of articles published in the local newspapers. He could also wheel and deal behind the scenes. As an influential member of the Boston caucus, he exerted considerable influence on the selection of local officers and the direction of the town meeting; as clerk of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, he figured prominently in that body's continuing resistance to the dictates of Crown-appointed governors. He was, in sum, an extremely effective partisan of the “popular party,” and this caused his opponents in the “court party” (also called the “government party”) great consternation. In the words of a contemporary Bostonian, John Andrews: “The ultimate wish and desire of the high Government party is to get Samuel Adams out of the way when they think they may accomplish every of their plans.”

10

To get Adams “out of the way,” his adversaries called him a traitor. On January 25, 1769, a Tory informer named Richard Sylvester swore in an affidavit that seven months earlier, the day after a large crowd had protested the seizure of John Hancock's ship

Liberty

, he had overheard Adams say to a group of seven men on the street, “If

you are men, behave like men. Let us take up arms immediately and be free and seize all the King's officers.” Later, Sylvester claimed, Adams had said during one of his many visits to his home, “We will destroy every soldier that dare put foot on shore. His majesty has no right to send troops here to invade the country. I look upon them as foreign enemies.”

11