Fortress Rabaul (32 page)

Authors: Bruce Gamble

As history knows so well, the admiral’s dream was shattered. Once again Allied code breakers made the difference. The intelligence network’s deduction of the Japanese plans enabled Admiral Nimitz to position three carriers for an ambush near Midway. In a dramatic battle that began on June 4, the Pacific Fleet sank four enemy carriers and a cruiser in exchange for the loss of a single flattop and one destroyer. The resounding victory belonged to Nimitz, not to Yamamoto.

News of the disaster sent shock waves through Imperial General Headquarters. Lieutenant General Shinichi Tanaka, chief of the Military

Operations Section, reputedly stated: “

We have lost supremacy

in the Pacific through this unforeseen great defeat.” Although it was not a deathblow to the Imperial Navy, the disaster severely impaired its aeronautical branch. More skilled aviators were killed in one day than could be trained in an entire year. The combined losses from the Coral Sea and Midway battles included five aircraft carriers and more than four hundred planes, bringing the navy’s offensive capabilities to a standstill.

Deeply shaken, Yamamoto accepted full responsibility for the defeat. The blame was not his entirely—the stunning reversal of fortune had been caused by carelessness and overconfidence at multiple levels—but by virtue of his position as commander of the Combined Fleet, he was accountable.

On June 10, as Yamamoto’s fleet steamed back toward Japan, the Information Bureau issued a brief statement that two American carriers had been sunk at Midway in exchange for one Japanese carrier sunk and another damaged. It was one of the most egregious lies yet uttered by Tokyo. To prevent the truth from leaking out, the Imperial Navy immediately clamped a tight lid on the disaster. Almost every sailor and airman involved was reassigned, either to highly restricted bases in Japan or to the far-off South Pacific. Even the wounded were sent into seclusion. Captain Fuchida, a hero of Pearl Harbor and other early actions, was wounded aboard the carrier

Akagi

at Midway. Arriving in Yokosuka aboard the hospital ship

Hikawa Maru

, he was whisked to a naval hospital in the middle of the night and held in complete isolation, a form of captivity he likened to being a prisoner of war in his own country.

Weeks after the defeat, the Information Bureau presented its “official” version of events, again using Captain Hiraide in a national radio broadcast. “As you are well aware, our Navy units, raiding Midway on June 5, wrought terrible havoc on the remaining American aircraft carriers,” stated Hiraide. “They sank an aircraft carrier of the

Enterprise

class, another carrier of the

Hornet

class, a heavy cruiser, and a destroyer, crushing the remaining American air force in the Pacific. Considerable significance is attached to the Midway and Aleutians operations in that our Navy, by crushing American Navy and air remnants in the Pacific, has brought pressure to bear on the United States mainland.”

It was all smoke and mirrors. Tokyo had taken its fabrications to a whole new level, and the public was none the wiser. The better part of

a decade would pass before the truth of the defeat was revealed to the Japanese people.

Thanks to the calm demeanor of Emperor Hirohito, Yamamoto and his staff began a gradual recovery from the disaster. Envoys from the Imperial Palace visited them aboard the battleship

Yamato

on June 16, bringing word that Hirohito was “not too concerned about the recent defeat; such things were to be expected in war.”

The message of forgiveness was a tonic for Yamamoto, but in Tokyo, tumultuous debates raged throughout Imperial General Headquarters as army and navy planners argued over ideas for the next stage of the Southern Offensive. The fallout from Midway affected both services. A planned invasion of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa, known as FS Operation, had been scheduled to begin in mid-July but was postponed for two months. Soon after that decision was made, the operation was abandoned altogether. Among the reasons for scrapping it: a newly published report from the Imperial Navy citing several problems in the South Pacific.

The ten-point position paper, submitted by the navy’s Operations Section on July 7, revealed multiple concerns. First, the service frankly admitted that the New Guinea campaign had degraded “into a war of attrition.” Navy leaders also acknowledged that they faced “a huge challenge” in replacing the four hundred plus aircraft lost during the Coral Sea and Midway battles. As of late June, land-based fighter units averaged only 54 percent of their full complement. Reconnaissance units were at 37 percent, medium bombers at 75 percent, and seaplanes at 80 percent. The Tainan Air Group, now divided between Rabaul and Lae, was a prime example. On paper, it had a nominal strength of more than fifty pilots and was allotted forty-five Zeros; but from May through July of 1942, the air group averaged only about twenty combat-worthy fighters. The supply line for replacements was described as “very sluggish,” namely because not enough new aircraft were coming from the factories. The monthly output of all naval aircraft was only slightly ahead of attrition levels, and the navy was particularly disappointed in the slow delivery of fighters—less than ninety aircraft per month in the spring of 1942.

Yamamoto and the Combined Fleet Staff should not have been surprised by the deficiencies. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries built the majority of its Type 0 fighters at the Nagoya Aircraft Works, a huge factory in the densely crowded port city of Nagoya. The plant had recently been enlarged to

more than 1.6 million square feet and boasted a workforce of some thirty thousand people, but for all that, it did not produce complete airplanes.

Due to a combination of industrial congestion and inconceivable shortsightedness, the aircraft factory had been built miles from the nearest airfield. As a result, the plant was restricted to producing subassemblies rather than whole planes. The engine, wings, fuselage, and tail section all had to be transported

thirty miles

to an airfield big enough for assembly and testing. There were no rail lines available, and the streets of Nagoya were too narrow for large trucks. Horse-drawn wagons had been tried, but their speeds over the narrow, rough roads caused too much damage to the aircraft components. Thus, the Japanese resorted to using primitive oxcarts to haul the subassemblies of their modern fighter to Kagamigahara airfield. It took twenty-four hours for each team of lumbering oxen to cover the thirty miles through the crowded streets. No improvements were made to the roads, which deteriorated as production rates increased and more oxcarts were employed. Determined to build more Zeros, the Imperial Navy contracted with another aircraft manufacturer, Nakajima, whose plant eventually exceeded Mitsubishi’s in monthly production; but even at their highest output, the two factories averaged only 140 fighters per month.

BY LATE JUNE, the leaders at Imperial General Headquarters had revised the entire strategy for the war in the South Pacific. Rather than extending their territory by invading far-off islands, they decided to strengthen their grip on the islands already occupied—namely the Bismarcks and the Solomons. Virtually overnight, the prevailing mindset among the military leadership reverted from an offensive strategy to a predominantly defensive one. As part of a fleet-wide reorganization, the Eighth Fleet was formed in mid-July. It was commanded by fifty-three-year-old Vice Adm. Gunichi Mikawa, headquartered at Rabaul, who would be responsible for operations in the Southeast Area, thus freeing the Fourth Fleet to concentrate its forces in the Central Pacific.

There was one exception to the defensive posture. The Japanese were not content merely to occupy the northeastern coastline of New Guinea—they wanted the whole island. By capturing Port Moresby, they could still force Australia out of the war. Conversely, as long as the Allies held Port Moresby, their attacks on Rabaul and its satellite bases would gradually intensify.

Having failed to capture Port Moresby by sea, Imperial General Headquarters began to investigate the feasibility of an overland assault against the Australian outpost. To some, the idea of sending a large infantry force across the Owen Stanley Mountains seemed preposterous. However, due to the Coral Sea and Midway losses there would be no carrier air support for another seaborne attempt, and the planners were anxious to try something different.

The outcome was called the Ri Operation Study. On June 12, Imperial General Headquarters issued Great Army Instruction No. 1180, which directed the Seventeenth Army to “immediately begin research, in cooperation with navy units in the area, for the feasibility of an overland attack on Port Moresby from the north coast of British New Guinea.” Because the Seventeenth Army lacked its own planes, aerial support was provided by the 25th Air Flotilla in the form of reconnaissance flights over New Guinea and heavy pressure on Port Moresby. Seven large-scale bombing raids were conducted during the first three weeks of July, typically employing twenty or more

rikko

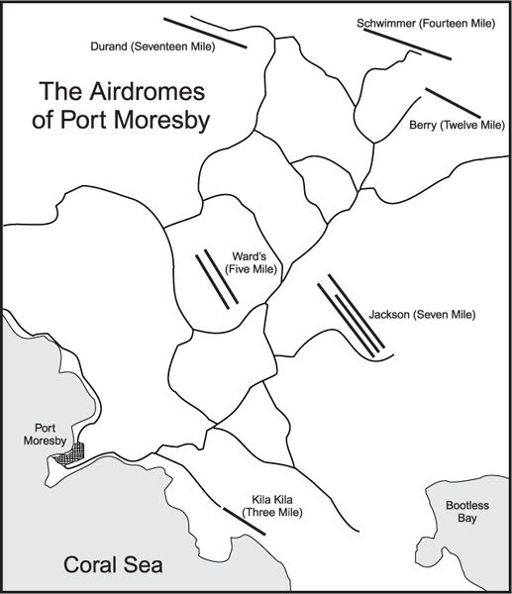

escorted by at least fifteen fighters. But rather than producing the desired knockout blow, the missions became more and more costly for the Japanese. Not only had Port Moresby survived the earlier onslaught of raids, it was now undergoing significant expansion. Over the past few months, Australian and American engineers had completed several new airdromes, enabling more squadrons of P-39s and P-400s to move up from Australia. Although still outclassed by the Zeros, the American fighters intercepted the Japanese raids in ever greater numbers.

As with Seven Mile airdrome, the new fields were initially named for their distance by road from Port Moresby. The first, constructed by an Australian militia battalion, was called Five Mile. Its two parallel runways, each 6,000 feet long, were surfaced by American engineers. Farther from town, near the village of Bomana, Twelve Mile airdrome was completed in mid-May 1942. It had a hard-packed gravel runway of 4,500 feet, a length suited for fighters, medium bombers, and reconnaissance aircraft. Two miles farther out, Fourteen Mile was completed by American army engineers near the Laloki River. Its dirt runway, 5,300 feet long, was later resurfaced with pierced steel planking, commonly known as Marston mat. In August, engineers completed Seventeen Mile airdrome, carved out of a mostly wooded area north of the Waigani swamp. Crocodiles and other

fearsome reptiles shared the wetlands, and one snake killed by airmen allegedly measured twenty-six feet in length.

All of the fields were constructed in haste. Their living conditions were deplorable, but the overall improvement in offensive and defensive capability was incalculable. The Japanese could see this for themselves. Despite the fact that the Tainan Air Group boasted more aces than any other air group in the Imperial Navy, they could not gain the upper hand. “

As the months passed at Lae

and the air battles grew in intensity, our supplies gradually diminished,” recalled Saburo Sakai. “Despite the excellent fighting record of our own wing of Zero fighters, we found it impossible

to pin down the Allies. They appeared in ever-growing numbers in the air. Coupled with their always persistent aggression, they proved a formidable force, indeed.”

Losses among the Airacobra squadrons were heavy, but the relatively inexperienced American pilots held their own against the veterans of the Tainan Air Group. For one thing, the American pilots could afford to be a bit more reckless when fighting near their own airdromes. If shot down (presuming they suffered no debilitating wounds in air combat), they stood a much better chance of surviving than if they came down over enemy territory. During May 1942, the first month of combat for the Airacobra squadrons, twenty P-39s/P-400s were shot down with eleven pilots killed or missing in action. In June, twenty-three Airacobras were shot down or crash-landed while intercepting enemy raids, costing the lives of seventeen pilots. In comparison, the Tainan Air Group lost eleven Zeros and nine pilots in May, followed by the loss of five Zeros and four pilots in June. Although the Americans were losing more planes and pilots, replacements were available. This was not the case for the Japanese. As Saburo Sakai hinted, the Tainan Air Group was slowly being used up.

In addition to predominantly fighting over their own airfields, the American pilots held another potential advantage: motive. What Sakai referred to as “persistent aggression” by the Airacobra pilots was actually vengeance. The attack on Pearl Harbor had occurred only six months earlier, and retribution remained a powerful incentive for the Americans. In the most basic terms, they wanted to kill Japanese. The end result was that two of the Tainan Air Group’s best attributes—superior aircraft and extensive combat experience—were whittled away by the sheer determination of their opponents.

CHAPTER 18