Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 (4 page)

Read Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

China 1937 on the eve of war

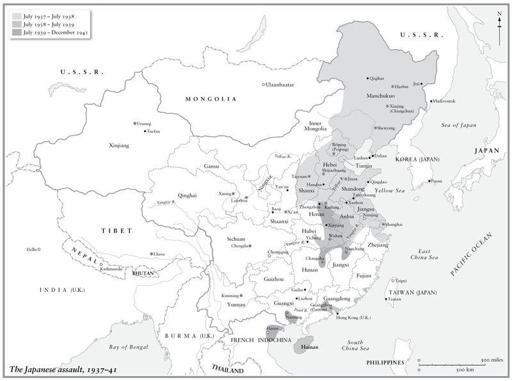

The Japanese assault, 1937–41

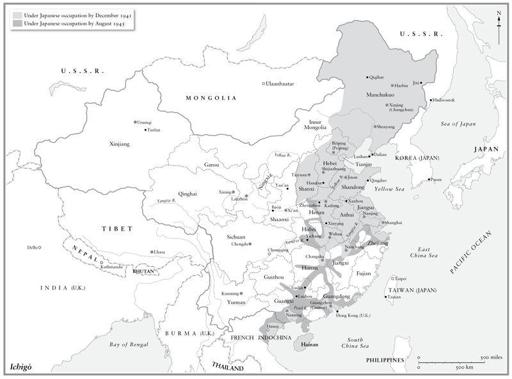

Ichigô

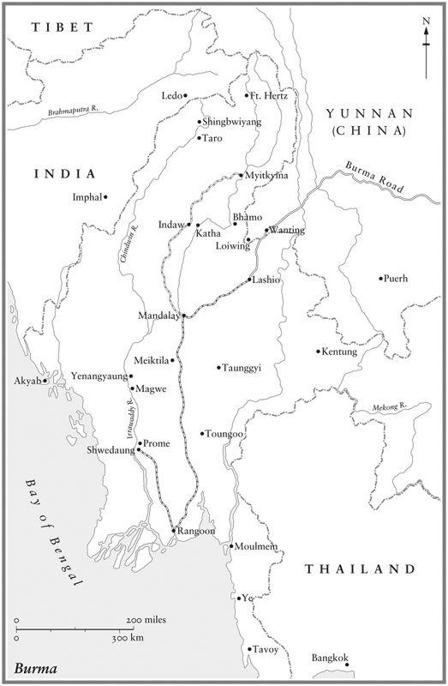

Burma

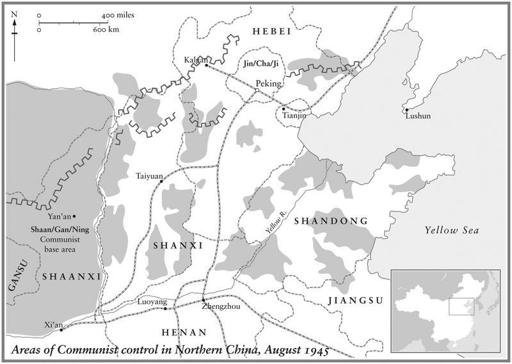

Areas of Communist control in Northern China, August 1945

I

THE PATH TO WAR

Chapter 1

As Close as Lips and Teeth: China’s Fall, Japan’s Rise

T

HE CLASH BETWEEN CHINA

and Japan did not begin in 1937. It had been brewing for decades. The story of the first half of China’s twentieth century is the story of its love-hate relationship with its smaller island neighbor. The hatred became more prominent as the years went on, reaching its climax with the devastation visited on China’s territory by the atrocities of the 1930s and 1940s. But in earlier years, Japan had been mentor as well as monster. It was an educator: thousands of Chinese students studied there. It was a refuge: when Chinese dissenters such as the prominent revolutionary Sun Yat-sen were threatened by their own government, they fled to Tokyo. And it was a model: China’s reformist elites looked to Japan to see how an Asian power could militarize, industrialize, and stand tall in the community of nations. For good or ill, a large proportion of the history of twentieth-century China was made in Japan. It became commonplace in both countries that Japan and China were “as close as lips and teeth.”

1

But if they were so close, how did the two nations come to fight one of the bloodiest wars in history? To understand the origins of their conflict, we must return to the late nineteenth century. To be Chinese during this period was to face a depressing range of political problems—floods, famines, and foreign invasions among them. And looming over all of these challenges was the greatest existential crisis in China’s history. The country’s elites had come to realize that they were no longer in charge of their own destiny. What had once been a self-confident civilization was now the victim of a new international system in which industrialization and imperialism shaped the world. That decline was doubly difficult for many Chinese to understand because it seemed to have come about so quickly. Just a century earlier, many observers in the West had felt that China’s empire was surely the greatest on earth: Voltaire, for one, had criticized his native France by comparing it unfavorably with China. For centuries China’s imperial dynasties had ruled over one of the most populous and sophisticated societies on earth, and for nearly a thousand years China had used a system of competitive examinations to recruit government bureaucrats, long before such a system operated in the West.

The cultural influence of China was at its zenith during this period. The orderly, conservative philosophy of Confucianism, which underpinned Chinese statecraft, spread across East Asia, shaping societies beyond China’s borders, including Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia. Chinese calligraphy, painting, and metalwork became renowned across the region, and the country developed a dynamic commercial economy: goods such as exotic fruits from the warm south made their way onto the sophisticated palates of the prosperous merchants in the cities of central and northern China. The rulers of Japan, in contrast, began to feel vulnerable. Concern about the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese missionaries eager to convert the Japanese to Christianity led the Tokugawa family, who ruled on behalf of the emperor, to impose a policy known as

kaikin

or

sakoku

from 1635: on pain of death, no Japanese were permitted to leave the country, and foreign trade was heavily restricted with Dutch, Chinese, and Korean traders permitted only on the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki Harbor and on outlying islands.

2

The Chinese court was much less concerned about the threat from abroad. When the British diplomat Lord Macartney attempted to open up trade between China and Britain in 1793, the emperor sent him away empty-handed, declaring loftily: “We have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need of your manufactures.”

3

Still, despite this imperial insouciance, China was highly integrated with the world economy and was very far from being closed or isolated. During the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) the distinctive blue-and-white pottery of Jingdezhen in central China graced elegant homes in eighteenth-century Britain and France. The spread of New World crops such as sweet potato and maize enabled the Chinese to move west and cultivate large parts of their territory that had previously been considered barren. Between 1700 and 1800 China’s population doubled, from 150 million to 300 million people.

4

The best example of China’s cultural power over its neighbors is the founding of the final dynasty, the Qing, in 1644. The dynasty was established by ethnic Manchus who rode into the Chinese heartland from the lands of the northeast. Even though the Manchus, like the Mongols and other non-Chinese invaders before them, had conquered China’s territory, they still respected China’s powerful social norms. The greatest emperors of the Qing, Kangxi (r. 1661–1722) and Qianlong (r. 1735–1796), sponsored large scholarly encyclopedias and wrote poetry to show how attuned they were to traditional Chinese culture (even though they maintained many customary Manchu forms at court and in wider society).

Yet China’s success contained the seeds of its future problems. Although the country’s territory expanded during the eighteenth century, its bureaucracy remained small, as did its ability to extract taxes. The lack of government revenue meant that military spending was low. This problem would be highlighted when a new threat appeared in the early nineteenth century: imperialism from the West. The new arrivals were different from previous conquerors who had established new dynasties. They did not share a Chinese view of the world, nor of China’s central place within it. They were led by the British, who were invigorated by the economic gains of industrialization and their final defeat of Napoleonic France at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. British traders had established the East India Company in 1600 and now sought a market for the products that emerged from their possessions in southern Asia.

5