Forever Barbie (27 page)

Authors: M. G. Lord

This is not, however, to let Barbie off the hook. In the doll's early years, before women spoke openly about anorexia, Barbie's

props encouraged girls to obsess on their weight. In addition to pink plastic hair curlers, Barbie's 1965 "Slumber Party"

outfit featured a bathroom scale

permanently set at

110.

Mattel also gave her bedtime reading—a book called

How to Lose

Weight

that offered this advice: "Don't Eat." Ken, by contrast, was not urged to starve. His pajamas came with a sweet roll and a

glass of milk.

THERE IS NO WAY TO AVOID PLUNGING INTO THE EATING disorder wars here, because for some, Barbie is a symbol of them. I say

"wars" because experts disagree on why many women succumb to destructive, diet-related behaviors and others don't. I should

say up front that I never had an eating disorder. As a teen, I was neither fat nor thin. I saw skinny models in

Vogue

and

Mademoiselle,

but never once thought of missing a meal. This doesn't mean I can't empathize with the many women for whom eating involves

more than the mere slaking of hunger. But in high school, I was too preoccupied with homework, swim-team practice, and the

domestic responsibilities that fell to me after my mother's death to evolve rituals around food.

To puzzle out why I had escaped the dietary scourges that afflicted many of my contemporaries—and to determine whether Barbie

might have had a small manicured hand in inducing such blights—I interviewed therapists who treat anorexics, bulimics, and

compulsive eaters. I read Kim Chernin, Susie Orbach, Louise J. Kaplan, and Naomi Wolf. And what I found were contradictions.

In

Female Perversions,

Kaplan interprets anorexia not as a movement toward an idealized Barbie body, but as a flight from it. The anorexic transforms

herself through emaciation into a sort of "third sex," liberated from menstruation and covered with a downy, masculine fuzz.

"Behind [the anorexic's] caricature of an obedient, virtuous, clean, submissive, good little girl is a most defiant, ambitious,

driven, dominating, controlling virile caricature of masculinity," Kaplan writes.

There is no universal consensus on why women become obsessed with dieting. One group of theorists views the problem as the

result of a conspiracy. Now more than ever, the evil media have enshrined freakishly thin models who make normal-sized women

feel like hippopotami. Another camp says, "So what?" As long as people have lived in communities, there have been community

"standards of beauty" which, by definition, have been both arbitrary and hard to meet. Yet another group says it isn't the

standards of beauty, but the importance a young girl places on them, which is a reflection of how her family feels about them

and the degree to which her family encourages nonconformity. If Mom is so threatened by her daughter's chubbiness that she

ships the girl off to a kiddie fat farm, the daughter may develop a lifelong neurosis about food. Likewise, if Dad makes clear

that only slender women are sexually desirable, his daughter may obsess on appearing slender.

One theme, however, recurs in much of the diet-disorder literature: Mothers are involved in how daughters view their bodies.

"While it might be hard to imagine the subtle transactions that occur around feeding in infancy, they are obvious during adolescence

when the young woman's body changes precipitate a whole range of reactions around the family dinner table," Susie Orbach explains

in

Hunger Strike: The Anorectic's Struggle as

a Metaphor for Our Age.

Mothers frequently encourage their teenage daughters to eat differently, as a way of losing baby fat or clearing up their

complexions. Thus food restraint "becomes the domain of the two females who may either cooperate or squabble over it."

Reading Orbach, I had a chilling thought about my own adolescence. I had owned Barbie dolls, studied fashion layouts, and

done all the girl-things that were supposed to have made me a slave to the bathroom scale. Yet I couldn't have cared less.

What was missing from my picture? Bluntly: Mom.

This is not to blame all mothers for infecting their daughters with an urge to compare their bodies unfavorably with the cultural

ideal. But historically, through words and actions, mothers have interpreted and taught the looks and behaviors associated

with "femininity" to their daughters. To place this in perspective, Chinese foot binding, a stunning cruelty in the service

of "beauty," was not literally imposed by men upon women. Rather, it came about through "the shared complicity of mother and

daughter," Susan Brownmiller explains in

Femininity.

"The anxious mother was the agent of will who crushed her suffering daughter's foot as she calmed her rebellion by holding

up the promise of the dainty shoe, teaching her child at an early age that the feminine mission in life, at the cost of tears

and pain, was to alter her body and amend her ways in the supreme effort to attract and please a man."

Nor is it as if mothers impart damage consciously. Given mothers' biological capacity to nourish their young, it is hardly

surprising that tensions between them and their daughters might be played out through food. "Women are traditionally the primary

feeders," explained psychotherapist Laura Kogel, a faculty member of the Women's Therapy Center Institute in Manhattan (founded

by Susie Orbach, Luise Eichenbaum, and Carol Bloom) and a coauthor of

Eating Problems: A Feminist Psychoanalytic Treatment

Model.

"So whether the woman is breast- or bottle-feeding, food and mother tend to be one."

Abby, a thirty-two-year-old Vassar graduate and recovering anorexic, feels very strongly that family dynamics rather than

idealized images of women contributed to her eating disorder. "I grew up in Greenwich Village," she explained. "I was the

child of a single mother who was a devout feminist. I wasn't allowed to watch TV until I was thirteen because my mother believed

that its patriarchal stereotypes would have a bad influence on the way I identified myself as a woman. Instead, I was given

Sisterhood Is Powerful

and

Ms.

magazine. My mother hated Barbie and what she represented. I wasn't allowed to have a Barbie, much less a Skipper or a Midge.

And the irony is that I was severely anorexic as a teenager. When I was fifteen, I stopped eating. I'm five foot nine and

at my lowest weight, I was just under a hundred pounds. I lost my period for three years. Today, I have come to realize that

my anorexia was a reaction to a very controlled and crazy family situation. I became obsessed with being thin because it wasn't

something my mother valued. I think overreacting to Barbie—setting her up as the ultimate negative example—can be just as

damaging as positing her as an ideal."

"My eating disorder had nothing to do with my Barbie dolls," said a forty-year-old novelist who prefers that her name not

be used. "The year my mother took me out of boarding school, I was totally miserable. She was really punishing me for getting

ahead of her—for going to this fancy school. She was horrible to me when I got home—really cold and cruel. And I decided to

stop eating, but I was so afraid of her that I felt I had to disguise it. The one meal we all had together was dinner, and

I became the family cook. I cooked these beautiful meals that I barely ate. It was my hunger strike to make her acknowledge

what she'd done. I was going to starve myself until she was nice to me. It's amazing that I eat today." She laughed. "All

my friends' mothers noticed that I was losing weight, but my mother said nothing—until the following year when I was on birth

control pills and I gained a few pounds. Then she said I was getting fat."

"When I deal with a family and with mothers," Kogel told me, "because I don't like mother-blaming and because I am a mother,

I try to see the fullness of the mother—as a three-dimensional person with her own insecurities, anxieties, and strengths."

Yet to understand is not always to exculpate. For one of Kogel's clients' mothers, "appearance was everything. She just shamed

her daughter at every moment. She said, 'You're fat; you're ugly.' The daughter has recently looked at pictures of herself

as a child and she was actually adorable. There were no gross deformities. But the mother took all the badness inside herself

and projected it onto her daughter."

Because of my own experience, I have a hard time attributing eating disorders to a cultural conspiracy—an idea that is easy

to discredit through caricature, as Elizabeth Kaye did in

Esquire.

Kaye quotes Naomi Wolf's description of the alleged fashion cabal in

The Beauty Myth:

"It has grown stronger to take over the work of social coercion. . . . It is seeking right now to undo . . . all the good

things that feminism did for women." Then Kaye adds, "This is the language of a science-fiction writer describing the Blob."

Yet because there are profits to be made off women with negative body images, people do fan the members of negativity. In

1992, columnist Ann Landers, a citadel of nonparanoid thinking, published some words of caution for "those who are borderline

nutty on the subject of weight loss." They included statistics showing that the diet industry had expanded to $33 billion

a year and that women spent $300 million each year on plastic surgery. By age thirteen, 53 percent of American high-school

girls were unhappy with their bodies. And even I began to half-believe the conspiracy theorists in January 1993, when Columbia

Pictures announced that it had winnowed about thirty pounds off the woman in its logo, transforming her into a torch-bearing

skeleton.

Sadly, in the eating disorder wars, the conspiracy camp is about as likely to shake hands with the family pathology crowd

as Queen Elizabeth is to host a fund-raiser for the IRA. Which is too bad, because the "cause" of an eating disorder seems

to vary between individuals, and involves some combination of cultural and familial issues.

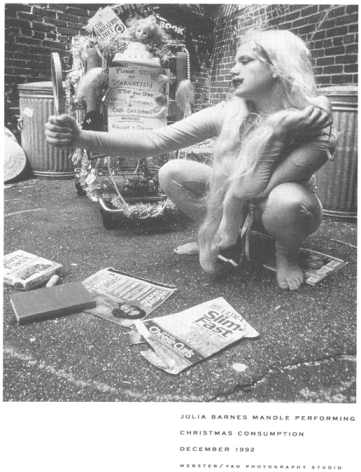

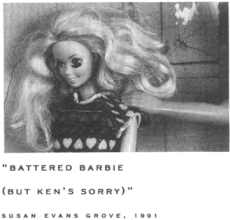

One of the most sensitive dramatizations of an eating disorder and its conflicting causes is Todd Haynes's 1987 movie

Superstar,

a forty-three-minute documentary written with Cynthia Schneider that uses mutilated fashion dolls to enact the death of seventies

pop singer Karen Carpenter from anorexia nervosa. Although the concept sounds like a campy bad joke, the movie is profoundly

affecting. "In

Superstar,

Haynes vindicates Karen from the junkyard of popular culture, forcing us to rethink her achievements," Joel Siegel wrote in

Washington's

City Paper

when the film came out. "I had ignorantly dismissed anorexia as a uniquely capitalistic affliction, a self-induced neurosis

that ironically compels the over-privileged to mimic the physical deprivations of the starving poor. Haynes and Schneider

convincingly argue that anorexia is a manifestation of a specifically

female

oppression, a terrifyingly logical response to the demands imposed upon women by a sexist culture."

In

Art Forum,

artist Barbara Kruger observed: "It is this small film's triumph that it can so economically sketch, with both laughter and

chilling acuity, the conflation of patriotism, familial control and bodily self-revulsion that drove Karen Carpenter and so

many like her to strive for perfection and end up simply doing away with themselves." The only people, it seems, who didn't

like

Superstar

were Karen's family and executives at A&M Records. They denied Haynes permission to use her songs and sent cease-and-desist

letters so threatening that Haynes withdrew the film from circulation.

By dramatizing the story with Barbie-like dolls, Haynes recalls Beauvoir's thoughts on how society pressures women to be "live

dolls," who slowly lose a sense of themselves as people. But society is not the only culprit. Anorexia, the film explains,

"is often the result of highly controlled familial environments." And the parent dolls in Haynes's movie are nothing if not

controlling.

The film opens with the voice of the doll portraying Mrs. Carpenter. "Nearly quarter-after and Saks is jammed by eleven,"

she chirps. When Karen doesn't respond, she walks to Karen's bedroom and finds Karen in a closet, sprawled dead—a victim,

we later learn, of an overdose of ipecac, a drug that induces vomiting.