Folklore of Yorkshire (25 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

The Reformation attempted to sweep away well worship, like so many popular medieval Christian customs, once and for all. But, as in numerous other cases, it was only partially successful and whilst such veneration declined in the fifty years immediately following the dissolution of the monasteries, the continental fashion for spa waters ensured that it soon made a comeback, albeit in modified form. Although Protestantism found the doctrine of saintly intercession unconscionably idolatrous, it was not averse to the idea that ‘heavenly grace was concentrated at particular locations’. However, they revised the mechanisms by which this was thought to occur, providing a pseudo-scientific veneer so that wells were thereafter venerated for their supposed miraculous mineral properties. Nonetheless, this led to the rejection of the pure water of many medieval holy wells, in favour of those with a high iron or sulphur content – and a correspondingly astringent flavour.

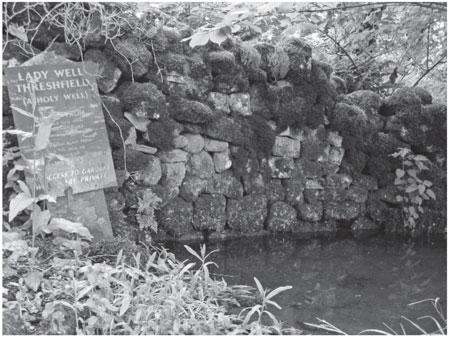

It was also during this period that certain holy wells developed a reputation for curing specific ailments. During the Middle Ages, saintly intercession was regarded as effective for any complaints but, now couched in medical terminology, the claims made for wells needed to be smaller and more credible. The most common disorders treated at wells from the sixteenth century onwards were connected with the eye: St Akelda’s Well at Middleham, St Helen’s Well at Eshton, St John’s Well at Harpham and Lady Well at Threshfield were all known for their potency in this regard. Some other wells were more specialised: St Peter’s Well at Barmby-on-the-Marsh was thought to treat scurvy; St Mungo’s Well at Copgrove cured rickets; and St John’s Well at Harpham was also known to tame wild animals. The only genuinely effective wells, however, were those whose unusually cold waters offered respite to rheumatics, such as St Peter’s Well in Leeds.

Despite the scientific façade with which many wells were now presented, the rituals performed at them were still very much a product of the pre-modern mind. For instance, rather than take a course of the mineral water, a single draught or one-off bodily immersion was usually held to be sufficient for the well to work its cure. Meanwhile, one of the most widespread customs was for a visitor to tear a strip from their clothing and tie it to some branch beside the well; leaving it there symbolised leaving their infirmity behind and it was thought that as the rag decayed, so would their illness diminish. During the eighteenth and nineteenth century, it was often noted that the trees around the St Helen’s Wells at Walton and Eshton were festooned with rags for this purpose. The practice was also noted at St Oswald’s Well in Great Ayton, but the garment of the sick person was first thrown into the well; if it floated, then its owner would recover, but if it sank, the prognosis was dire.

Such divination was often frequently practiced at wells up until the nineteenth century. At St John’s Well, near Mount Grace Priory, people wanting to make a wish would stick a pin through an ivy leaf and float it on the water; the direction in which the pin turned would indicate the likelihood of favourable response. More typically, lovesick girls would simply cast a crooked pin into the well whilst wishing for a vision of their future husband and this practice is extensively recorded at Lady Well in Brayton. The pins were believed to be an offering to the fairy who presided over the well, and a story from Brayton relates that the fairies wished to use the pins for their arrowheads, but having no power over iron they could only obtain it through such a trade. An association between fairies and wells was quite common in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, and it may be that the presiding fairy represented a corrupted memory of the well’s former saintly patron.

However, the precise symbolism of the crooked pin is uncertain. Some writers have suggested a link to the ritually damaged votive offerings deposited by many prehistoric cultures, but like other connections between well worship and pre-Christian religions, this is tenuous at best. Oblations are a feature of many faiths and it is common to find offerings left at Christian shrines today. Hence, during the Middle Ages, the pin may have been connected to some more ornate item of jewellery and represented a more significant sacrifice, which eventually lost its meaning and value when mass-production of pins began during the Industrial Revolution. Meanwhile, crooked items were often considered ‘lucky’ in previous centuries, such as a crooked sixpence carried as a talisman and immortalised in the nursery rhyme.

It is clear that as the centuries passed and medical science advanced, the practice of praying for healing at wells had evolved into more generalised wishing. Whilst the rags that were tied to the trees around St Helen’s Well at Walton may once have been intended to represent a visitor’s ailment, the comments of nineteenth-century writers suggest they were now more typically left as an offering to ensure the fulfilment of their heart’s desire. Sometimes there was a more elaborate ritual to be performed. For instance, anybody hoping for their wish to be granted at Lady Well, near Roche Abbey, had to take a sip of water from the well then hold it in their mouth whilst they walked backwards up the hillside and passed through a hole in an old tree, mentally repeating their wish the whole time.

Much as Protestantism had been unable to suppress the practice of leaving offerings at wells, it was similarly unable to defeat the popular notion that well waters were more potent on certain days of the year. In the case of holy wells with medieval provenances, this was still often the day of the feast of the saint to whom the well had been dedicated; whilst for post-Reformation spa wells, a more universal holy day was chosen, such as Palm Sunday or Ascension Day. Lady Anne’s Well near the ruins of Howley Hall at Morley in West Yorkshire was supposed to run with a variety of colours at six o’clock in the morning of Palm Sunday. Local legend added that sometime in the seventeenth century, a lady of Howley Hall by the name of Anne Saville, used to bathe in the well. On one such occasion, she fell asleep by its side, whereupon she was fatally attacked by some wild animals from the surrounding woods and the well was named in her memory.

Spaw Sunday celebrated in Cragg Vale. (John Billingsley)

The mill-workers of Batley and Birstall visited the well on Palm Sunday to take the chalybeate waters at St Anne’s Well, and the annual Feldkirk Fair grew up around it. Such occasions would regularly see large crowds congregate at certain wells to drink the water and were the scene of much ‘rowdyism’. In Calderdale, spa celebrations were held on the first Sunday in May, known as ‘Spaw Sunday’, and taken very seriously indeed. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, great numbers of people from across the valley made pilgrimages to spa wells in Luddenden and Cragg Vale. The practice has recently been revived at the latter and now pilgrims process to the well from the church of St John in the Wilderness, although many are reluctant to taste the strongly sulphurous waters and content themselves with a sniff.

Of course, a well did not have to be known for its healing properties for a folk tradition to develop around it. The Ebbing and Flowing Well, near Giggleswick, is a particularly famous example whose waters can rise and fall by several inches, sometimes a number of times over the course of an hour. The action is caused by a complex geological siphon in the surrounding hillside, but in his epic topographical poem of 1612, ‘Poly-Olbion’, Michael Drayton records a more colourful tradition. He claims the area was once home to a beautiful but shy nymph, who had the misfortune to be seen by a lustful satyr. This beast pursued her with dark intentions and as his quarry grew weary from the chase, she fell down panting and begged the gods for salvation. In response, they took the curious decision to transform her into a spring:

The Ebbing and Flowing Well at Giggleswick — a transformed nymph? (Kathryn Wilson)

Even as the fearful nymph then thick and short did blow

Now made by them a spring, so doth she ebb and flow.

Despite the fame of this legend, it is unlikely that it was a genuine local tradition and may be Drayton’s invention entirely. Spirits such as nymphs and satyrs belong to Greco-Roman mythology, not Yorkshire folklore, and the tale seems more likely to have sprung from the imagination of an Oxford Classicist than a Craven hill-farmer. A more typically indigenous tale connected to the Ebbing and Flowing Well suggests it was once the retreat of an old wise-woman who gave the highwayman, Will Nevison, a magic bit for his mare; an artefact which allowed the horse to vault previously unimagined distances and so throw off pursuit. A number of limestone gullies in the Dales bear the title ‘Nevison’s Leap’ and on one occasion, the horse is even reputed to have cleared the vast chasm of Gordale Scar.

Meanwhile, at Harpham, the beat of a drum was once supposed to echo from a well close to the old manor house upon the death of any member of the Quintin family, formerly squires of the village. It is said to be the spirit of Tom Hewson, who served as a drummer-boy to the Quintin family in the Middle Ages. Legend relates that he was knocked into the well during an archery tournament as an enraged Squire Quintin pushed past him to scold an incompetent contestant. By the time Tom’s body was retrieved, he had drowned, much to the anguish of his mother, Molly Hewson, a local witch. In her grief, she decreed: ‘Squire Quintin, you were the friend of my boy, but from your hand his death has come. Therefore, whenever a Quintin, Lord of Harpham, dies, my poor boy shall beat his drum at the bottom of this fatal well.’ The site is known today as the Drumming Well and another such well was once recorded at nearby North Frodingham, but its tradition is less defined.

Phantoms are often associated with holy wells, but their legends are typically much more vague. A white lady wandered near Lady Well at Catwick, accompanied by the cry of an unseen baby; whilst a one-eyed, hooded woman haunted Holywell at Atwick, variously reputed to be the spirit of a murder victim buried there, or a nun from nearby Nunkeeling Priory. Equally, many wells – such as Thruskell Well near Burnsall – were regarded as the haunt of generic entities such as Jenny Greenteeth or Peg-o-the-Well, who would drag children who got too close into the well’s murky depths. Doubtless such stories were widely employed by cautious parents trying to keep their children from drowning, but often the role of ‘bogeyman’ was the final function of a belief that had once been sincerely held by the adult community (

See

Chapter Eight).

The Drumming Well at Harpham from which a drum beats on the death of a local noble. (Kai Roberts)