Folklore of Lincolnshire (21 page)

Read Folklore of Lincolnshire Online

Authors: Susanna O'Neill

RAF Scampton has a few other ghosts to keep the dog company. A pilot in a life jacket has apparently been seen in the control tower at the airbase and voices have been heard talking in the crew room, even when it was empty. There is also the report of one pilot greeting Lieutenant Salter as he entered the officer’s mess, during the First World War. The officer acknowledged him and carried on his way, and it was only later the pilot discovered Salter had died that day in an air crash many miles away and could not have been in the mess at all. A Roman soldier is also said to have been seen walking across the runway.

At the former RAF base at Metheringham, the ghost of a young woman, Catherine Bystock, is said to appear. In life she was a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and engaged to be married to a flight sergeant. She was only nineteen when she was involved in an accident whist riding pillion on his motorbike on the bomber base and was killed. Reports have varied; some say they have seen a girl in a RAF uniform flagging cars down and asking for help for her injured fiancé. However, no fiancé was ever found upon investigation, and when the motorists looked around the girl had vanished too – in some cases leaving behind a scent of lavender.

There are many more hauntings, ghosts, strange sightings and inexplicable occurrences in Lincolnshire’s history – too many to mention them all here, but this is a very interesting subject to research if ghosts rattle your chain.

W

ITCHCRAFT

AND

C

UNNING

Witches are not merely mythical crones on broomsticks who fly with their cats at Halloween. They were once imagined to be a major problem in society. The country was apparently overrun with them and like vermin, they were pursued and exterminated. But who were these infamous witches and where did they come from?

Unfortunately, they were usually normal women who became scapegoats during an era of ignorance and superstition, as illustrated in this chapter.

The European witch trials of the Middle Ages is not a period of history we should lightly forget. Present scholars estimate that the number of people who were executed ranges between 40,000 and 100,000, one source suggesting that more than 2,400 of these were Lincolnshire women. There is evidence that as early as 1417, a witch was tried in Sleaford for using divination to trace a thief.

Witchcraft and sorcery are age-old practices, spreading back to when our race was young. One example of this is the

Code of Hammurabi

, which is an ancient law-code not dissimilar to the Ten Commandments. This document, from Babylon, has been dated to 1790

BC

, with 282 laws existing on clay tablets. It seems that the first two laws concern witchcraft, with frighteningly familiar – if perhaps slightly fairer – punishments:

1. If a man has accused another of laying a death spell upon him, but has not proved it, he shall be put to death.

2. If a man has accused another of laying a spell upon him, but has not proved it, the accused shall go to the sacred river, he shall plunge into the sacred river, and if the sacred river shall conquer him, he that accused him shall take possession of

his house. If the sacred river shall show his innocence and he is saved, his accuser shall be put to death.

The book

Malleus Maleficarum

(which translates as

The Hammer of Witches

), subtitled

Which Destroyeth Witches and their Heresy like a Most Powerful Spear

, was written in fifteenth-century Germany and became one of the powerful forces behind the terrible witch hunts that followed.

In the present day we use the term ‘witch hunt’ to refer to any situation in which someone is persecuted without any concrete evidence – guilty unless proved innocent. Unfortunately, many of the witch trials focused on drawing confessions out of the accused, often through methods of torture or trickery. The witch hunts and trials of the past were spurred on by fear, propaganda, ignorance and misunderstandings.

In many cases, women accused of being witches were healers or those with knowledge of herbal remedies. Alternatively, they may have had a squint in their eye, or a hunched back. They may have angered a neighbour or aroused suspicion by displaying unusual habits or keeping pets. Midwives were common targets, because if they could bring life into the world they might decide to take it away.

As the persecutions increased, more methods of torture for extracting confessions were developed. One such technique was the use of large boots of leather or metal into which boiling water was poured, or sometimes wedges were hammered up the length of the boot into the wearer’s legs. Thumbscrews or

turcas

were used to tear off fingernails. Red-hot pincers, crushing, stoning, and the cutting out of the tongue were punishments often employed, together with sleep/light/warmth deprivation and torment with pins. The Witch Finder General’s favourite, the swimming test, was amongst the tortures endured. Whilst bound, the accused were lowered into water where, if they sank and drowned they were innocent, but if they floated they would be tried as witches. A physician serving in a witch prison is said to have talked about women who were driven half mad by such techniques:

…by frequent torture…kept in prolonged squalor and darkness of their dungeons…and constantly dragged out to undergo atrocious torment until they would gladly exchange at any moment this most bitter existence for death, [they] are willing to confess whatever crimes are suggested to them rather than to be thrust back into their hideous dungeon amid ever recurring torture.’

1

It is hardly surprising that so many confessions were forthcoming!

The Scottish Forfar Witch Hunts of the 1600s and the Pendle Witch Trials in 1612 are two of the most famous cases in the UK. Lincolnshire, which boasted its very own Witch Finder General, had a case almost as infamous as these; the Witches of Belvoir.

The Earl and Countess of Rutland, who resided at Belvoir Castle near Grantham, employed as servants, in 1618, Joan Flower and her daughters Margaret and Philippa.

Apparently, the countess became dissatisfied with the family, claiming Margaret was pilfering items from the castle, Philippa was conducting lewd activities with her lover and Joan, the mother, was an ungodly and spiteful woman whom she no longer wished to employ. The three were not dismissed immediately but Margaret, who was the only one residing at the castle, was sent home. It seems that it was this action that moved Joan Flower to exact revenge, in the form of cursing the countess’ eldest son, Henry. Henry became sick and died shortly afterwards, whilst his younger brother Francis also became ill. Katherine, his half-sister, suffered sudden fits and this ‘overwhelming evidence’ resulted in the arrest of Joan Flower and her daughters, who were taken to Lincoln Prison.

Belvoir Castle, near Grantham; open to the public.

Joan proclaimed her innocence, demanding the opportunity to prove her case. She allegedly asked for bread and butter, announcing that if she was guilty of witchcraft then she would choke on the bread. The story goes that at the first bite Joan did choke, dying shortly afterwards. This was judged as proof that she had been practising witchcraft against the earl and countess and their family, so the two daughters had no choice but to ‘confess’.

They disclosed that Joan had acquired one of Henry’s gloves, dipped it in boiling water, stuck pins in it and rubbed it on her familiar, Rutterkin the cat. She then went on to boil the gloves, along with some bed feathers of the earl and countess, in blood and water, attempting to render the couple barren.

A familiar was the special pet of a witch, which was thought to actually be an imp or demon that took on the form of an animal and aided the witch in her Devil worship. These creatures were said to survive by sucking parts of the witch.

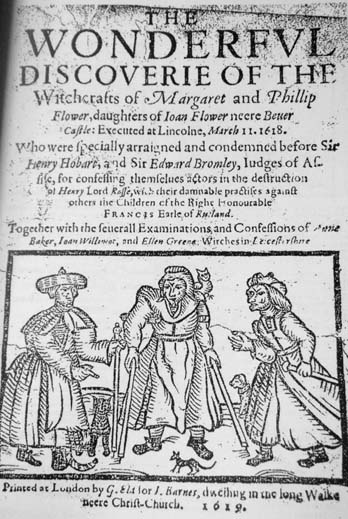

The title page of the first edition of the

Belvoir Pamphlet

, 1619, accusing Joan Flower and her daughters of witchcraft.

A pamphlet concerning these events, named ‘The Wonderful Discovery of the Witchcrafts of Margaret and Phillippa Flower, daughters of Joan Flower neere Bever Castle: executed at Lincolne, March 11th 1618’ was compiled by one John Barns and details extracts of their confessions. The following is an example, concerning Margaret Flower:

She saith and confesseth, that about four or five years since, her mother sent her for the right hand glove of Henry, Lord Roos, afterward that her mother bade her go again into the castle of Belvoir and bring down the gloves and some other things and she asked ‘What to do?’ Her mother replied ‘To harm my Lord Roos.’ Whereupon she brought down a glove, and delivered the same to her mother, who stroked Rutterkin her cat with it, after it was dipt in hot water, and so prickted it often, after which Henry, Lord Roos fell sick within a week, and was much tormented with the same.

The girls also confessed to experiencing demonic visions and owning familiars of their own, which they allowed to suck at their bodies, then they went on to betray the names of three other women they claimed were also involved.

Anne Baker of Bottesford, Ellen Greene of Stathorne and Joan Willimot of Goodby were duly arrested and eventually made to confess. All three made admissions to consorting with familiars of their own, in the form of a kitten, a mole and a white dog. Ellen Green testified:

Joan Willimott called two spirits, one in the likeness of a kitten, and the other of a moldiwarp (a mole): the first, said Willimott was called Pusse, and Hisse, [sic] and they presently came ot [sic] her, and she departing [sic] and they leapt upon her shoulder, and the kitten sucked under her right ear on her neck, and the mole on the left side in the like place. After they had sucked her she sent the kitten to a baker of that town (i.e. Goadby) whose name she remembers not, who had called her a witch and had stricken her, and had her said spirit go and bewitch hime to death: the mole she then had go to Anne Dawse of the same town and bewitch her to death, because she called this examinate witch, whore, Jade etc, and within one fortnight after they both died.

The women also confessed to having visions, consorting with fairies and uttering curses against people. John Barnes’ pamphlet states that Anne Baker was accused of murder by witchcraft:

Being charged that she bewitched Elizabeth Hough, the wife of William Hough to death, for that she angered her in giving her almes of her second bread [i.e. stale]: confesseth that she was angry with her and she might have given her of better bread for she had gone too often on her errands.

He also states that between 1615 and 1618, there were up to eighteen people who were believed to have been injured or killed by witchcraft in the Vale of Belvoir. This again highlights how a crowd can be easily incited by gossip and superstition.

Even though the Flower daughters had already been executed when Francis, the Rutland’s youngest son, died in 1620, it was believed by all to be a result of the curses they had inflicted upon him. When the earl died, an inscription was placed at St Mary’s Church in Bottesford. This can still be seen there today: